I once read in a book that feeling at home provides an added layer of homeostasis. The idea is that a person’s surroundings can keep them—even at the level of the body—stable and capable of working toward a good life. At least that’s how I understood the chapter. Since then I’ve thought of anyone’s neighborhood as a giant hammock, of sorts, or a large personal cocoon, or a third kind of love.

We love our families and friends, and sometimes we fall in love, and sometimes that love is for a place. One measure of love is mourning. If you mourn a place after you lose it, that probably means you love it. This is one way to think about what happens when people lose their place to gentrification (and natural disasters, and leaving home).

Many of the hundreds of thousands who have called D.C. home have lost their beloved places to development, or departed under the pressure of rising rents. Many among the transient set—the ones who move in and then leave a few years later, and can often pay the high rent—call another place home.

D.C. is a city in flux. People here find spots that provide them with a measure of sanity, or, if they stay long enough, spots that become part of their identity.

Caroline Jones, City Paper’s managing editor, had the idea for this collection. It’s based on a 1998 City Paper story called “Private Monuments.” (Get it? Personal monuments, private moments.) For this collection, 21 years later, I invited back many of the original 1998 writers to participate alongside City Paper’s current writers. Look for Jandos Rothstein, Holly Bass, Bradford McKee, Eddie Dean, and Jonetta Rose Barras.

Rothstein organized the original collection. He says that then-editor David Carr approved the concept, but he has always suspected that Carr ultimately doubted the value of it. (It’s hard to say what’s true, given that Carr died in 2015.)

Carr did choose a spot—the northwest corner of Albemarle and 42nd streets NW. “We pull up to the stoplight at 8:37 every morning on our way to school. The twin girls in the back sneak a kiss onto my cheek—a safe half-block from the school where their friends might notice,” he wrote.

Rothstein’s 1998 intro said: “To live in—to love—any town compels you to carve a landscape that means something out of the raw urban material around you. But in Washington, those personal monuments are crucial, because they are all that you have. The Washington that the world thinks it knows is the one we have no use for. The D.C. we know and love is hiding.”

I dug up the theory I’ve been counting on all this time. It’s in a book called Separation: Anxiety and Anger by British psychologist John Bowlby. He wrote, “it is clear that, so long as the systems that maintain an individual within his familiar environment are being successful, the loads placed on the systems that maintain psychological states are being eased.”

I couldn’t say whether my interpretation of his work is right on or stupid, but I’m sure that what follows is a collection full of love. —Alexa Mills

Under the East Capitol Street Bridge

Before it was paved as part of the Anacostia Riverwalk Trail, the rocky road that separated River Terrace from Anacostia was a pathway to adventure for kids in the ’90s. Unbeknownst to our parents, my brothers and friends and I would bike from our Northeast neighborhood along the dirt road and across the train tracks to the outdoor skating rink in Anacostia. The entry point for the journey was under the East Capitol Street Bridge. This is where the older kids cautioned us of possible dangers that lurked in the woods and warned us that if we panicked mid-trip, we’d have to find our way back home, alone. Though my heart palpitated each time, I refused to be left behind. By high school, the space under the bridge became a safe haven. Though traffic roared overhead and bats hid in the shadows, it was a source of light, tranquility, and hope. My best friend and I would meet under the bridge to trade secrets and vent about our teenage woes. We would plot our escape to the mysterious piece of land across the Anacostia River, which we now know is Kingman Island. I often reminisce about the time I spent under that bridge, and I rely on memories of youthful freedom and exploration to get me through adulthood. —Christina Sturdivant Sani

The Spanish Steps in Kalorama

Let me preface this recommendation with a disclaimer: These steps are poorly named. Their title refers to the grandiose, iconic, and popular stairs in Rome, and I’ll admit it, these steps are none of those things. On the contrary, they are small, unimportant, and probably only popular with me. But for someone who doesn’t have the time, money, or emotional energy to invest in a getaway to Italy, Kalorama’s Spanish Steps are a delightful alternative for some peace of mind. The concrete staircase sits on 22nd Street NW between S Street NW and Decatur Place NW, surrounded by trees and plants and adorned with benches and a small fountain. Despite their proximity to Dupont Circle, the steps are quiet and secluded, characteristics that aren’t easy to come by in D.C., and although they’re no architectural feat, they’re charming. I suggest visiting them to picnic, write, read, catch your breath on a run, kiss your crush, or call your grandma. She will thank you, and you will thank me. —Ella Feldman

Coolidge Auditorium at the Library of Congress

Whenever I attend a show at the Coolidge Auditorium, it feels like hallowed ground. The small, intimate concert hall—fancy enough but in no ways stuffy—is nestled inside the Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress, impervious to the outside world. The renowned acoustics of the auditorium, built nearly a century ago to host chamber ensembles, make for a world-class venue for its eclectic (and free) concert series. On any given day you can wander in and hear Maryland bluegrassers pay tribute to mountain-music legend Ola Belle Reed or a female band from Niger perform traditional Tuareg music.

Much of my abiding fondness for the place comes from what happened here in 1938, when folklorist Alan Lomax of the LOC recorded forgotten jazz pioneer Jelly Roll Morton, who he’d found operating a U Street NW dive. With busts of Beethoven and Brahms looking on, Morton commandeered a grand piano onstage at the Coolidge for an audience of Lomax alone, at his feet with a Presto disc-recording machine. “I had a bottle of whiskey in my office. I put it on the piano,” said Lomax, recounting how he kicked off the five-week session with the musician he dubbed the “Creole Benvenuto Cellini.” “As I listened, I realized that this man spoke the English language in a more beautiful way than anybody I’d ever heard.” —Eddie Dean

Hains Point

When it’s not underwater, Hains Point is a terrific place to visit.

Located at the tip of the 327-acre East Potomac Park, Hains Point offers a unique place of urban solitude for reflection and thought while the world of Washington roars all around it. (I didn’t say quiet solitude.)

If you sit just right on the lone, broken picnic bench and stare straight ahead, you barely can discern the Wilson Bridge far to the south. National Airport recedes in your peripheral vision on your far right, as does Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling on your left (where White House presidential helicopters flap-flap-flap to and fro.)

Hains Point is named for Peter Conover Hains, a U.S. Army General who designed the Tidal Basin to reduce sewage stink, and later helped lay out the Panama Canal. The Point’s expansive grass field used to be home to “The Awakening”, a sculpture of a giant trying to free itself from the earth, until its private owners sold it off to National Harbor.

Fun Fact: Hains Point is sinking. All of East Potomac Park floods now more than ever. The U.S. Park Service doesn’t have the millions of dollars it would take to rebuild and protect crumbling walkways and sinking grounds of this man-made island that was created by dredging the Potomac. And yes, it is an island, not a peninsula as people often describe it. The four-mile road leading to and from Hains Point is a haven for cyclists and pedestrians. You pass a golf course and an outdoor pool to get there.

Go and sit at Hains Point before it slips into the river water. —Tom Sherwood

Kennedy Center, Back of the House

In 1991, I had a handsome, thrilling new boyfriend who got me a job working with him catering at the Kennedy Center. We earned great money—New York union wages, basically. Made a bunch of friends. Served huge dinners fixed by the very good Chef Max to the likes of Sarah McClendon, Dan Quayle, Boris Yeltsin, and the whole power-helmet opera crowd of Washington. Our last gig was Bill Clinton’s first inaugural. We saw Sidney Poitier and Geena Davis. We biked home every night with armloads of flowers.

We carted food all over that building, which is vast. We learned the back corridors via secret elevators to take coffee to the Golden Circle Lounge, the Bird Room, the African Room, the Chinese Room. On the way, we’d cut through the areas that hold the performers’ practice and rehearsal rooms. The corridors were hard to learn, because there are a lot of them and they are all clean, with walls of white concrete block and plain floors. Sounds seemed to come out of the walls—woodwinds, strings, voices, the tunings, the sudden suite, made not for anyone on the spot, but for later. It was a perfect little world.

I returned last week just to inhale. I was surprised how little had changed. It still has pale white walls and neat signs to point the way. Orderly. No nonsense. One thing has changed, and that is the boyfriend, who after a marriage in 2015 became my husband. We still go back and look around. —Bradford McKee

Half Mile Gravel Loop Near the U.S. Capitol

On a cool September evening, I sidestepped a stream of kids chasing after their ball, weaved past parents pushing strollers, and tried my best to avoid photobombing what looked like a professional shoot. I didn’t mind the extra obstacles. It reminded me of my late 20s, when I would meet up with a friend every Wednesday night during the summer and fall months to run 400, 800, 1,200, or 1,600-meter repeats as part of my marathon training program. But instead of running on an actual track, we would show up on the corner of 7th Street SW and Jefferson Drive and sprint around the half-mile loop located between the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

I’ve run hundreds of miles on those gravel paths just two blocks away from the U.S. Capitol, and I still haven’t gotten tired of seeing the orange glow of the sun setting behind the Washington Monument. Even if it means having to dodge the occasional errant kickball. —Kelyn Soong

Pho 14 in Van Ness

I noticed when my favorite waitress got a slight, tasteful nose job. And when the menu changed, another waiter made sure to point out that my usual—a large number 10, add broccoli—would now be a number 6.

I moved to D.C. in February of 2017 when the town was cold, gray, and grumpy. I was alone a lot, and the hot noodle soup a few blocks from my new apartment was a cozy, cheap solution to the twitchy ennui that permeated the early part of that year.

Pho 14 is still my fallback when I’m looking to find some peace and comfort. Stomach ache? Pho. Tell a guy on a boring date I have to leave the bar to feed my cat? Pho. Need to craft the perfect text to tell a friend I can’t afford her destination wedding? A smaller bowl of pho, no extras.

I learned to get comfortable eating alone in public at Pho 14. A bowl of pho has been the accessory to every book I’ve read in the past two and a half years, though I do try a little harder to save library books from the inevitable broth splatter. —Elizabeth Tuten

The HIVE 2.0 in Anacostia

Tucked in the basement of an arts space in Anacostia lies the only co-working office Google Maps recognizes east of the river. The HIVE 2.0 occupies the lower level of the more well known Anacostia Arts Center, and despite its first location (on Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue SE) closing a few years ago, the HIVE 2.0 has continued to be a place where people can come to build up, refine, and execute their ideas. It is also the only work space that has ever felt organically affirming to me. Despite being underground, the HIVE 2.0 is a space of light, love, and grounding, and I go there whenever I’m struggling with the purpose of my work.

While on a job focused on Wards 7 and 8 that somehow had me based in Adams Morgan, I moved my office to The HIVE to get closer to the activists, artists, and entrepreneurs who don’t require a calendar appointment to “network” or need an explanation of how durags work.

In a city full of incubators and co-working spaces, I’ve never encountered a community management team so socially intelligent; they’ll connect you to the people and places you need to know to get things done. Whenever I’m in Anacostia I make it a point to stop by and see what startups are there and fall into conversation with someone I’ve just met about everything from the best wing spot in the city to the intricacies of city code and permits. —Hamzat Sani

Capital Checkers in Shaw

Against a backdrop of interlocking diamond shapes, our checker-playing man lounges elegantly near the corner of 8th and S streets NW. A dashing figure in slim-cut, pin-striped pants and pointy shoes, his matching waistcoat peeks from underneath a fitted black blazer adorned with white buttons. Though the matte surface of the mural gives no indication, I like to imagine his buttons are made of carved mother of pearl.

I’ve passed the low-slung brick building dozens of times, never noting any activity inside, despite the slightly askew white letters posted on the front declaring “Capital Checkers.” I naively assumed the mural was a tribute to some long-ago social club that had been displaced in the summer of ’68.

But one Friday evening, as I brought a friend to admire the artwork, we glimpsed an open door. An affable older gent with an easy smile welcomed us in. Tal Roberts has been the president of Capital Pool Checkers since 1982, and has played the game since the early 1940s. “Pool” refers to a particularly competitive variant of the game, popular in the South. And Roberts’ skills are so sharp, his nickname is The Razor. I’m not sure I even made four moves before Roberts swiftly dispatched me, but it was the most fun losing I’ve ever had. —Holly Bass

Kalorama Park

When covering a fractious D.C. Council or tracking the lunatic in the White House, or grappling with ordinary life issues overwhelms me, I often race through the gates at 1865 Columbia Road NW. I sit on one of the many benches inside Kalorama Park or stretch out on the grassy knoll of the three-acre site. The trees envelop me, giving me cover and comfort.

I am undisturbed by the sounds of players on the basketball courts; the chatter of mommies and nannies and laughter of children wildly zipping down the slide-board serve as soothing background music. D.C. isn’t some nondescript enclave of government agencies. It’s a city of families whose diversities are enriching.

I began going to Kalorama Park with my young daughter in the 1980s. Later, she and I took my granddaughter there, allowing her to travel at dizzying speed on the merry-go-round.

Things have changed. The merry-go-round is gone, replaced by more modern equipment. The landscaping is far better than it was when I wrote about John Cloud battling the city over its care. My daughter and granddaughter don’t visit anymore.

I cannot stay away.

Once, the land belonged to John Little. When Hortense Prout, a woman he enslaved, ran away in June 1861, he found her and had her thrown in jail for 10 days. The next year, in April 1862, President Abraham Lincoln freed slaves in D.C., including Prout. The Kalorama Citizens Association erected a marker in Prout’s honor in 2008.

It does seem odd that a place where people who look like me were once enslaved, now offers my mind and soul incalculable peace and freedom. —Jonetta Rose Barras

Malcolm X Park in Columbia Heights

On Saturday mornings just after sunrise, Malcolm X Park is quiet. If I wake up when it’s still dark, and spend 20 drowsy minutes brewing the coffee, I can trip across 16th Street NW, mug in hand, just in time for the park’s finest hour.

The big rectangle lawns will be picnic grounds all day, but at dawn a few lucky dogs and their owners have the green to themselves. A woman with handsome streaks of gray in her ponytail is usually power-walking the perimeter; she keeps a small purse slung over one shoulder for some reason. And this one man who sleeps on a bench is always at rest when I arrive, but by the time I’ve circled the grounds once, he’s up and organizing his things, maybe feeding the birds whatever snacks he has in his bag. One Sunday morning a man I’d never noticed before stopped to compliment my red mug, but asked why I wasn’t using the pretty black-and-white patterned mug I’d carried the morning before.

The advantage of all this is the opportunity to walk slow, or stop walking altogether and get stuck on a thought for five minutes, even 15 minutes. D.C. isn’t awake enough, at this hour and in this place, to shake my brain out of its nice fog. —Alexa Mills

Fort Reno Hill in Tenleytown

There I sit, taking in all of D.C. from its highest point, the top of the town: Fort Reno Hill. On a nice evening, a light breeze might be in subtle harmony with the buzz of cicadas as the sun sets, making silhouettes of the District’s skyline.

But the hill isn’t particularly beautiful. Its coarse grass stings the skin. The crushed red solo cups stuffed in the fence at its apex crudely spell the word “seniors.” The stale stench of marijuana is always present. But so is the sound of laughter and conversation, the music of high school camaraderie. Fort Reno Hill is a monument to teenage delinquency and late-night adventures, a refuge from the monotony of school, and a haven for people who don’t feel like kids anymore but are still terrified of adulthood. It feels like time stops on top of that hill—just you and the sky and a flattened Bud Light can. —Ayomi Wolff

Kahlil Gibran Memorial on Embassy Row

I was looking for parking near the British Embassy one day at work, and I found a lot more—a whole lot more. I found an oasis. Well, not an actual oasis, but a memorial dedicated to the author Kahlil Gibran is pretty damn close. During that time I was reading Gibran’s book, The Prophet. What better place could there be to read a book about enlightenment, right? “This isn’t just dumb luck, is it? I was supposed to find this place,” I thought to myself. And with parking finally (finally) secured, I walked the little stretch of land that leads to the memorial, strolling over a foot bridge that leads to a smaller section of Rock Creek Park that’s carved out to honor this man; the very man whose transformative book I held in my hand. I allowed myself some time to read a section of the book, breathe, and just be. It felt like time stood still for a while, which it did. But the parking meter gods didn’t notice. I got a damn ticket! Still, that was a $30 well spent. —Haywood Turnipseed Jr.

3211 Wilson Boulevard in North Arlington

3211 Wilson Boulevard betrays its origins as a private home less than it did 15 years ago, when small back rooms, long since sealed off, accommodated limited seating for coffee drinkers. But it still stands out as the oldest and funkiest property on a block that has somehow mostly escaped redevelopment in the Clarendon corridor. Newer and less human-scaled buildings surround it now. 3211 is so out of place, one wonders if it was once a farmhouse. It sports a stairway leading to an upstairs bar that is too narrow to accommodate two-way traffic, and has too few bathrooms for its tightly packed customers. Its walls look like they haven’t been painted since I first started coming here in 2004, when it was a coffee shop named Common Grounds.

I was here a lot back then, mostly to work on articles and eventually the bulk of my book. The story then was that it was owned by a young minister who wanted to spread fellowship along with cups of coffee (hence the name), but the only perceivable part of that abandoned effort was a shelf of religious books that were wholly ignored by the regulars who, like me, used the room as a bargain co-working space.

Somewhere around 2007 the minister grew bored, and it became the Arlington outpost of D.C.’s Murky Coffee, whose owners were so fanatical about the Zen of Arabica beans that they thought an April Fool’s blog post announcing their sale to Starbucks was self-evidently hilarious. They were less fanatical about paying taxes, a lapse that shuttered the D.C. location, and eventually the Arlington outpost, too. I had mostly stopped going by then—I didn’t foresee it, but finishing the book turned out to mean I was emotionally finished with the place where I wrote most of it.

Northside Social is housed there now—it’s still a sort of coffee shop, but bolstered by wine, beer, and the closest thing to a real kitchen the place has ever had. The old building lends a hipster cred, where it once only gave an impression of decay. My book is far enough behind me that I show up here every once in a while, but I think this article is the first thing I’ve written here since I concluded that project. Still, it’s possible to sit, basically in the same seat at the same long table I might have chosen back then, take in the room and look out the window, and contemplate one of the few small corners of Clarendon that is still (mostly) as it used to be. —Jandos Rothstein

Firehook Bakery in Cleveland Park

Before I lived in D.C., I came here often to visit my girlfriend, who is now my wife. I would drive up on a Friday and, while she was at work, post up in the Cleveland Park Firehook Bakery, which has a beautiful garden patio in the back. I’d sit with adults catching up over a cup of coffee to discuss very adult things like promotions and commutes, and I would make small talk with the owner and work on my college thesis, or job applications, or whatever grown-up thoughts occupied my mind at the time.

I would pretend I was one of those D.C. people you see in coffee shops at odd hours and wonder, what do these people do? And I thought about how, soon, I would live in the city and talk about promotions and commutes and actually be one of those people who do something, and I felt warm and tall and like every step led forward, instead of just ahead.

I still go there sometimes now. Mostly when I want to feel younger. —Will Warren

Meiwah Restaurant, Which Is Now Closed

Before Larry La’s Meiwah Restaurant shuttered its original location at New Hampshire Avenue NW and M Street NW last May, I liked to visit the take-out counter of this Chinese-American landmark eatery.

For me, Meiwah Restaurant was an oasis in an ever-newer and ritzier hotel district of a neighborhood. It wasn’t about Meiwah’s glory days of being a feeder of U.S. presidents and media types, memorialized in the signed portraits of famous smiles and handshakes decorating the wood-paneled walls. Rather, it had to do with small kindnesses from the unheralded women behind the counter working fast in a cramped space, taking orders, taking credit cards, and stapling paper bags, far from their childhood homes.

“Sit down,” they’d tell me matter-of-factly, seeing my cane. Despite my half-Chinese, half-Korean heritage, I’d order the same old stuff, wonton soup and lo mein with char siu. Thusly revealed in all my fifth-generation glory, I would watch as they thoughtfully placed a plastic fork in my bag. Not wanting to admit their assumption was correct, I’d ask for a set of chopsticks.

Collective identity can be contrasted with personal identity, as Kwame Anthony Appiah recently put it. Sometimes I long for an authenticity, rooted in my Asian collective identity, that I don’t have. Instead, I need to use my own sensibility in hopes of creating something real. —Diana Michele Yap

The Whole Thing

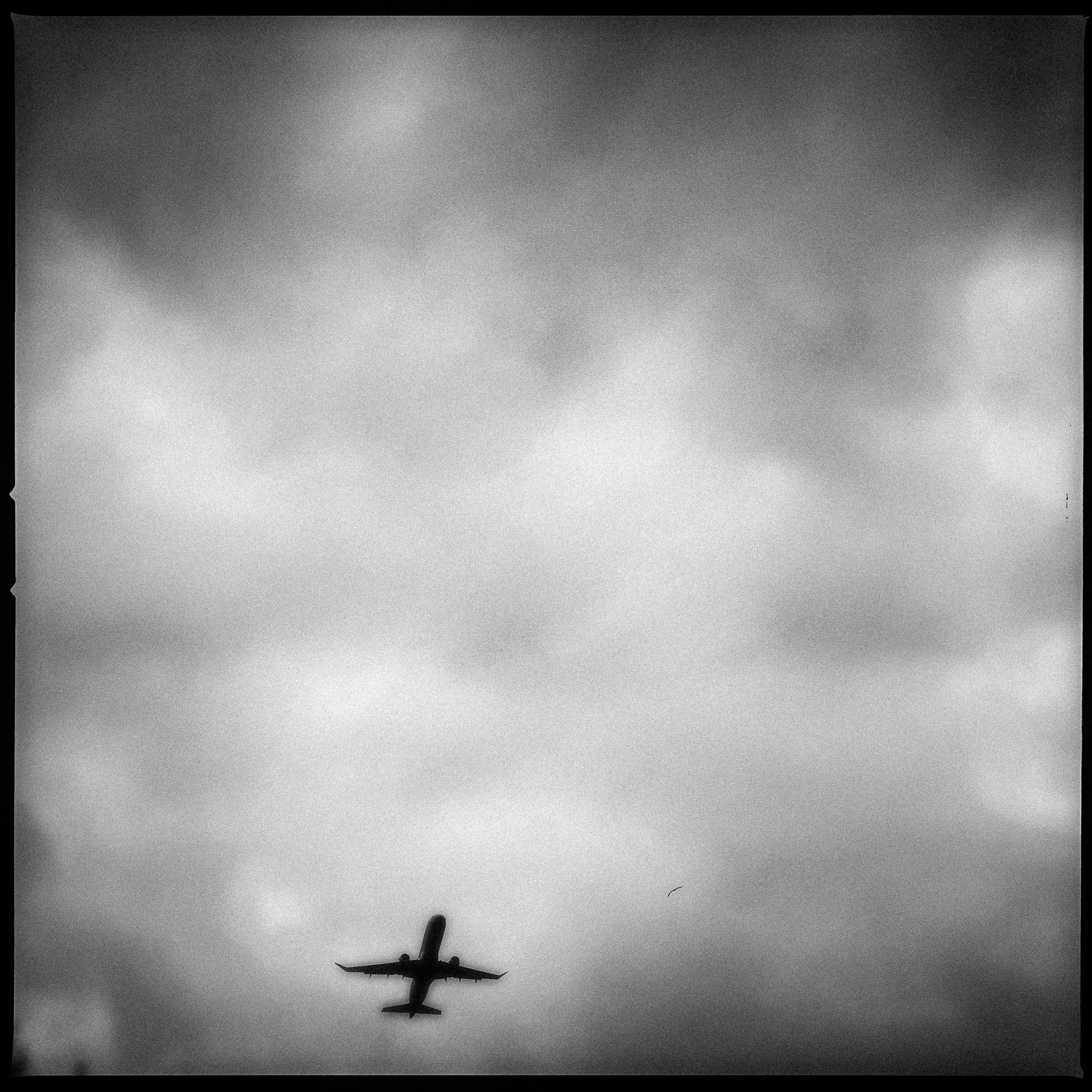

The view of D.C. is transfixing from National Airport. As the plane taxis and takes off, passengers with window seats are treated to a slow roll past the monuments and, on a clear night, a view of the glittering city from above. For me, the sight plays out like a game: How many places can you identify before the plane climbs too high? There are the obvious ones (Arlington National Cemetery and Kennedy’s eternal flame, the National Cathedral, the White House) and less obvious ones (Blue Plains Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant, Georgetown University’s somewhat surprising football field) and together, those views meld to create the sensation of home.

Despite its status as a world capital, D.C. looks like a small town from above. If you squint, you can almost make out the office buildings and buses. It’s nice to depart from them briefly and view them from a 10,000-foot remove, and it’s also nice to know that those places, be they monumental or ordinary, will be there waiting when you return. —Caroline Jones