10.0 MODULE OVERVIEW AND OBJECTIVES

Welcome to Module 10

This module includes the following three sections:

10.1 Introduction to transboundary waters

10.2 Overview of water conflict and international security

10.3 Water wars

Module objectives:

By the end of this module you should be able to

- Recognize that there are hundreds of transboundary water sources in the world. (Module 10.1)

- Recognize that there are hundreds of countries with territories in transboundary watersheds (Module 10.1)

- List some of the types of conflicts involving water (terrorist attacks, ethnic disputes, etc.) (Module 10.2)

- Discuss the “War of Wells” as an example of a conflict over water (Module 10.2)

- Describe how water conflicts can be avoided by taking preemptive action in areas identified as “hot spots” for water conflict (Module 10.2)

- Discuss how shared use of water resources can help avoid conflict by encouraging cooperation and shared governance (Module 10.2)

- List recommendations for making cooperative water agreements more successful (Module 10.2)

- Describe the main issues in the dispute between Georgia and Tennessee (Module 10.3).

- Discuss why the prospect of water wars is a popular subject in the media (Module 10.3).

- List reasons why widespread water wars are unlikely (Module 10.3).

- Know the following definitions.

- Transboundary waters

- Watercourse

- Riparian party

- Basin country unit

Module Assignments

Module 10 quiz: Check the course schedule in Canvas to see when you need to take the quiz.

10.1 INTRODUCTION TO TRANSBOUNDARY WATERS

First, let’s go over some definitions…

- Transboundary waters – “refers to any surface or ground waters which mark, cross or are located on boundaries between two or more States.” (UNEP, 2011). With respect to transboundary waters, the term “states” is often assumed to mean nations. So transboundary waters is often used to refer to water sources that cross international boundaries. However, the term can also be more loosely defined to refer to water sources that cross any type of socio-political boundary, including boundaries at local, regional, national, and international scales. Although conflicts over water often occur between competing users (e.g. agriculture and industry) within a shared socio-political region, transboundary water conflicts are of grave concern because of their potential to contribute to wide-scale political instability.

- Watercourse – a system of surface waters and groundwater that, by virtue of their physical relationship, constitute a unitary whole and flow into a common terminus.

- Riparian parties (or riparian states) – those countries or entities that have territory adjacent to a transboundary watercourse.

- Basin country unit – the portion of a transboundary river basin that belongs to the respective country. For example, the portion of the Nile River basin that is in Egypt would be referred to as the Egypt basin unit of the Nile Basin.

Transboundary waters include all types of water bodies including rivers, lakes, and aquifers.

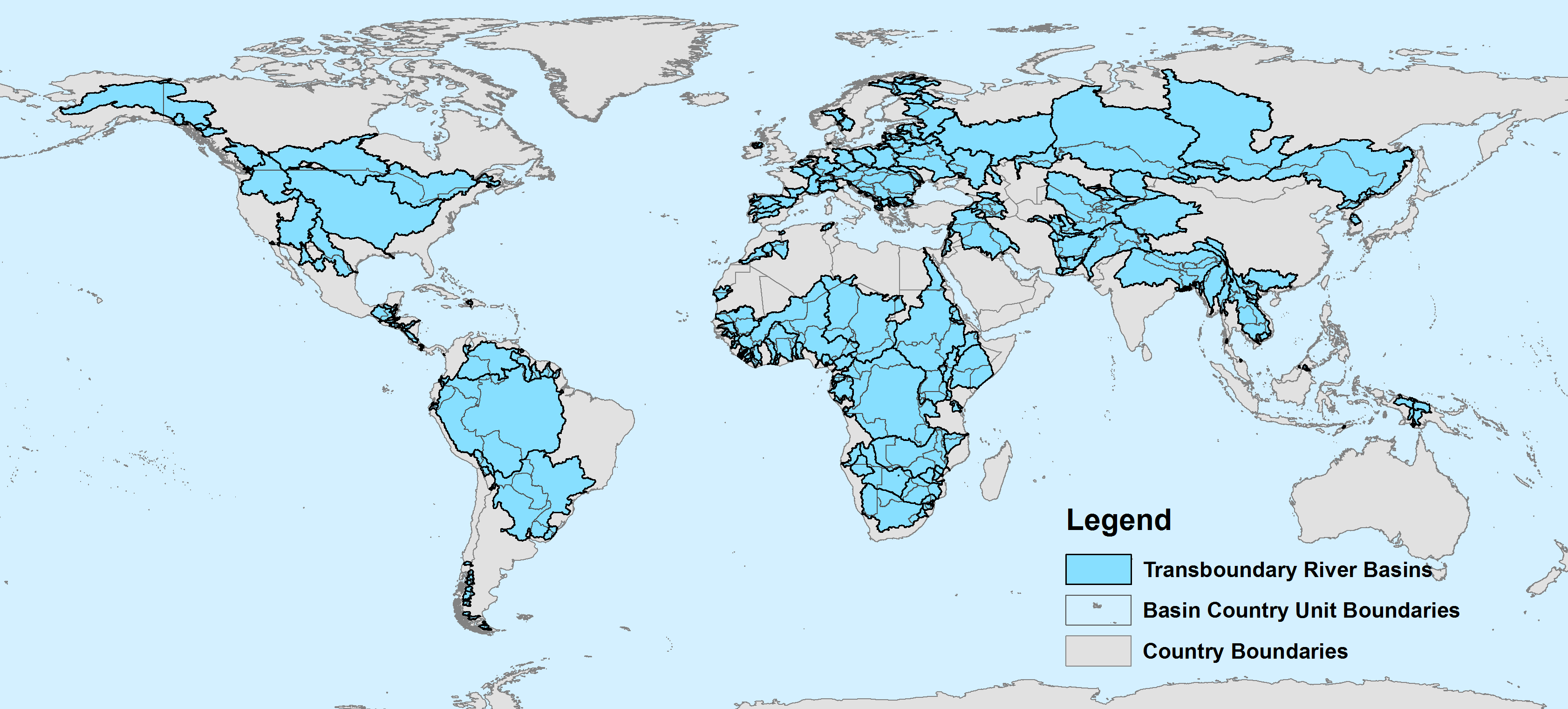

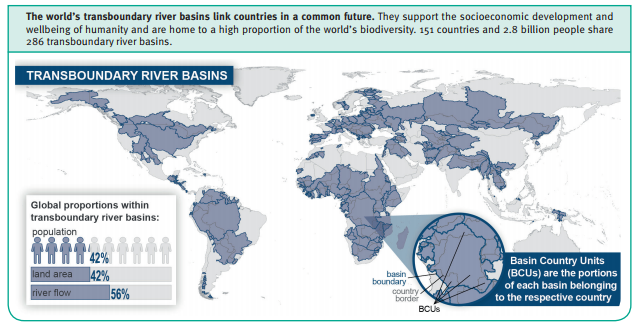

Transboundary River Basins

Globally there are 286 transboundary river basins. According to the Transboundary Waters Assessment Programme those river basins…

- span 151 countries,

- include more than 2.8 billion people (around 42% of the world’s population),

- cover more than 42% of the total land area on Earth, and

- collectively produce about 54% of the global river discharge.

“The water systems of the world – aquifers, lakes, rivers, large marine ecosystems, and open oceans – support the socioeconomic development and wellbeing of humanity and are home to a high proportion of the world’s biodiversity. Many of these systems are shared by two or more nations, and these transboundary resources are linked by a complex web of environmental, political, economic and security interdependencies. The interdependencies extend not only across national borders, but also between the different water systems, underlining the need for integrated management of these resources.”

From: http://twap-rivers.org/

10.2 Overview of water conflict and international security

Follow the link below and read through the paper to get an overview of water’s role in international security.

The article provides a nice overview of historical, current, and future water-security issues. As you read through the paper, pay particular attention to the following…

From the sections of the paper titled Water as an Instrument of Conflict you should be able to discuss the roles that water can play in conflicts:

- Widespread wars over water are not likely to occur in the foreseeable future.

- Conflicts over water can add to other regional tensions.

From the sections of the paper titled Water as a Tool in Ethnic Violence you should be able to discuss the ways that manipulation of water can be used as violence:

- Water resources can be a target in military operations, terrorist attacks, and ethnic conflicts.

- Recognize that manipulation of water (e.g. cutting off water supplies, poisoning water supplies, or causing floods) has been used as a military tactic for 1000s of years.

From the section of the paper titled The Recent Trend Toward Local and Regional Water Conflict you should be able to discuss the War of Wells as an example of water causing conflict:

- The article above briefly describes the War of Wells, but you should also check out this Washington Post article to learn more details about the “who, what, where, when, and why” of the War of Wells.

From the section of the paper titled The Way Forward recognize that by utilizing tools, like the water stress index, regions where there is a potential for conflicts involving water can be identified:

- Discuss how cooperative water agreements can serve as groundwork for lasting political stability by providing a motivation for cooperation and shared governance. To get a better feel for the current state of international water agreements, read through the first section of this webpage titled Transboundary Waters. Notice the large number of cooperative water agreements that have been signed – in some cases even in the face of significant political disagreements.

- Be able to list the following general recommendations for making cooperative water agreements more successful

- In general, cooperative water agreements need to more clearly specify how the agreements are going to be enforced.

- Agreements also need to include very specific procedures for resolving conflicts in the event that disputes arise.

- In order to be effective in the long-term, agreements need to incorporate the flexibility necessary to adapt to changing climates, sudden significant hydrological events, and changing socio-economic conditions.

Also check out the following webpage that has interactive maps and tables detailing a chronology of conflicts involving water. You should examine the interactive map section to identify what part of the world has the highest concentration of ongoing (2010-Present) water conflicts.

10.3 Water wars

The prospect of wars over water is often talked about, and increasingly media reports describe conflicts over water as “wars”. For example, this media report (be sure to listen to the audio on the story on this site) describes ongoing water waters between Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, and Florida. Although the ongoing arguments about water between Georgia and the other states are heated and have gotten to the level of the Supreme Court, they do not by any means constitute “war”. From the above report, pay particular attention to the following…

- Recognize that disputes over water occur worldwide, even in the United States.

- Summarize the conflict between the states. Who are the players? What water sources are the focus of the conflict? What are the underlying drivers of the conflict?

- Reflect on how this conflict relates to the material we covered about water rights in Module 6?

- The person being interviewed states “When we look at these river basins, we need to be looking at them as a whole, looking out for their health overall.” Reflect on how this statement relates to the watershed concept and watershed management that were covered in Module 4.

- What does the person being interviewed suggest is a better solution to the problem than trying to acquire rights to water from the Tennessee River?

As the following article explains, the prospect of water wars is appealing as a sensational news story. Also, because water is such a fundamental human need, it is easy to imagine fighting for the right to adequate water for survival. However, there is no evidence to suggest that widespread wars over water are likely in the foreseeable future. From this article you should recognize:

- Most nations have adequate water supplies for basic human needs. It is agriculture and industry that put extreme stress on water resources, and in times of dire need, water can be re-allocated to meet basic human needs.

- Adaptation to use less water and re-allocation of scarce water resources is less costly and less dire than going to war over water.

- There are few countries in the world that would have both the opportunity and capacity to invade another country in order to commandeer a water source.

Explaining the persistent appeal of water wars’ scenarios

TRANSBOUNDARY

December 15th, 2013

Frédéric Julien, University of Ottawa, Canada

from: http://www.globalwaterforum.org/2013/12/15/explaining-the-persistent-appeal-of-water-wars-scenarios/

Just weeks before the beginning of the International Year of Water Cooperation (2013), the US Intelligence Community warned that ‘[w]ater may become a more significant source of contention than energy or minerals out to 2030’, to the point that militarised ‘interstate conflict cannot be ruled out(1)‘. Though cautiously couched, this warning lends a surprising credence to the prospect of ‘water wars’. Indeed, a review of the academic literature shows that ‘an impressive research effort [ ] has, by and large, led to the conclusion that there is no substantive evidence for the water wars claim(2)‘.(3) Already, some bleak prophecies have passed their expiry date without materialising.(4)

There are many reasons behind the continuous appeal of water wars scenarios – notably, the existence of a widespread appetite for sensational stories as well as incentives for many actors to tell them(5,6,7,8) -, but their intuitive plausibility could be a key factor. After all, one needs only to imagine a drying up well surrounded by thirsty people to grasp the potential of violence related to the control of water. States, however, are not biological persons: they do not have clear and imperative water needs.

States can adapt to water scarcity

The satisfaction of basic water needs represents only a fraction of the water used in a given society and virtually every country in the world has enough water to cover these needs. In other words, thirst is more a political problem than a physical one – it does not demand more water to be solved.(9)

The real fears of water shortages concern agricultural and, to a lesser extant, industrial uses of water. For good reason: food production uses about 70% of all water withdrawals on the planet and the industry, 20%.(10) Yet, compared to the imperative need to drink of a single person, the agricultural and industrial water needs of an entire society are flexible.(11) The economy of Israel, for instance, is rich and diversified even though it uses volumes of water that would be considered widely insufficient in, say, Canada.

States can adapt if they reach a point where it is not possible anymore to withdraw additional water from nature for environmental or geopolitical reasons. Without even mentioning the possibility of ‘creating’ fresh water via desalination or water recycling and reuse, a state facing scarcity can try to control the demand for water with policies encouraging a more efficient (more crop or goods per drop) and profitable (more jobs or dollars per drop) use of water. By creating more economic value from its water endowment, a country can generate sufficient revenues to pay for the importation of food or other goods whose production is water intensive. A final level of adaptation refers to social and cultural changes, such as a shift towards a low-meat diet, leading to a more sustainable use of water.(12,13)

Of course, the adaptation process just described is easier wished for than implemented. Any attempt to reallocate water resources between different use(r)s will create ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ and will thus foster resistances.(14) Change means social stress and, in theory, a state could be tempted to externalise this stress by trying to increase its share of a transboundary water source.

As demanding as adaptation may be though, war remains the most expensive and uncertain way to ‘manage’ water scarcity. The late Avraham Tamir, an ex-Major-General in the Israeli army, is eloquent on this point: ‘Why go to war over water? For the price of one week’s fighting, you could build five desalination plants. No loss of life, no international pressure, and a reliable supply you don’t have to defend in hostile territory(15)‘. More cynically, governments all over the world have proven that they can simply ‘tolerate’ important levels of water misery without reacting much

States’ actions are not determined by water matters

Admittedly, the decision to go to war is not reducible to such dry cost-benefit analysis. Water wars might still be conceivable on some political or ideological ground. In practice however, states are not obsessed with water the way thirsty individuals are (and have to be). Although often dubbed ‘our most precious resource(16)‘, water is not the new oil; water is not at the centre of world capitalism.(17) In the Middle East, where water wars are supposedly more probable than anywhere else, researcher Jan Selby even observed that ‘[ ] with the waning economic importance of agriculture, water has become (and will continue to become) less and less central to the political economy(18)‘.

When looking at the world map, one quickly realises how difficult it is to point out a country where the state elite would have both the desire and the capacity to capture and control an important source of water on foreign soil. The most probable war-like scenario might be for Egypt, a regional power highly dependant on the Nile River, to bombard some hydraulic infrastructure upstream in Ethiopia to make sure that this country does not divert too much water.(19) Yet, interstate relations in the Nile region are far from having reached this stage. Indeed, beyond their sometimes bellicose rhetoric, the Nile riparian countries are currently engaged in the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), a partnership supported by the international community which aims to establish a cooperative framework for the management of the basin. The NBI may be progressing slowly, but it is a genuinely positive development in regard to regional peace.(20,21,22)

This is not to say that everything is for the best on the blue planet. Rather, one should not reason in hydrocentric terms and ‘[ ] conceptually jump from the necessity for water in human life to water as the determining factor in all decision-making and political choices23‘. There is no particular reason to focus on water scarcity as one of the main risk factors for future wars. Worse, framing water as a ‘national security issue’ can only nourish mistrust and rigidity between states and distract us from the actual consequences of water scarcity: socioeconomic hardship and ecological degradation.24 These problems are serious and urgent enough without any extra sensationalism.

This article received second prize in the Global Water Forum 2013 Emerging Scholars Award.

For list of references, following link at the top of this article.

Although, the chances of widespread water wars are much less likely than the media suggests, as the following excerpt from a UN report notes, the impacts of Climate Change on water resources will complicate already tense regions. From this excerpt you should recognize:

- Climate change is increasing security risks, including the risk of conflicts of water resources.

- Addressing climate change-related water resources issues offers opportunities for increased cooperation between and within countries.

- Climate change, water, and human security represent a nexus of very complex interactions that make it difficult to predict how climate change’s impact on water resources will affect human security.

Excerpt from: CLIMATE CHANGE, WATER CONFLICTS AND HUMAN SECURITY

https://www.zaragoza.es/contenidos/medioambiente/onu/1034-eng_climate_change_water_conflicts_and_human_security.pdf

Climate change has and will continue to have far-reaching impacts on environmental, social and economic conditions, which people and governments will be forced to adapt to. Increasingly, climate change and the associated increase in the frequency of extreme weather events such as floods, droughts and rising sea level is recognized as not only having humanitarian impacts, but also creating political and security risks that can affect national/regional stability and the welfare of people. This has led to increased political interest in the influence of climate change on water availability and human security. Specifically, whether climatic and hydrological changes and increasing variabilities trigger and multiply conflict at various scales or induce cooperation between and within countries and how this affects human security remains contested. There is a growing consensus in the climate change and conflict literature that climate change can be considered a threat multiplier for existing tensions. Besides climatic factors there are underlying causes such as poverty, weak institutions, mistrust, inequalities and lack of information and basic infrastructure that may also contribute to these tensions. In comparison, functional and well-adapted institutions can facilitate cooperation and conflict resolution and are therefore considered as threat minimizers that help to maintain human security. Climate change may impact directly or indirectly on any of the dimensions of human security. People and governments can adapt to these impacts, but their capacity to do so varies; it is dependent on a multitude of factors such as access to assets, knowledge, institutions, power relations, etc. Due to the complexities within the natural system and its interlinkages to the social, economic and political spheres, a highly complex nexus has evolved that connects climate change, water conflicts and human security. However, this complexity has made it difficult for researchers to measure the effect of climate change on conflict and human security.

END OF MODULE 10