Two years ago we pooled our experience as nongovernmental observers of the U.S. Military Commissions at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba—the most important terrorism cases in our country’s history—and developed a set of practical, bipartisan proposals for fairly and transparently expediting the halting pace of the proceedings [1].

We were motivated then, as we are now, not by a desire for a particular result by a particular date. Our concern remains the process—its integrity, its defensibility—and the degree to which chronic delays at Guantánamo risk undermining public faith in the American legal system.

The victims of these atrocities deserve a clear path forward—as a nation of laws, we all do.

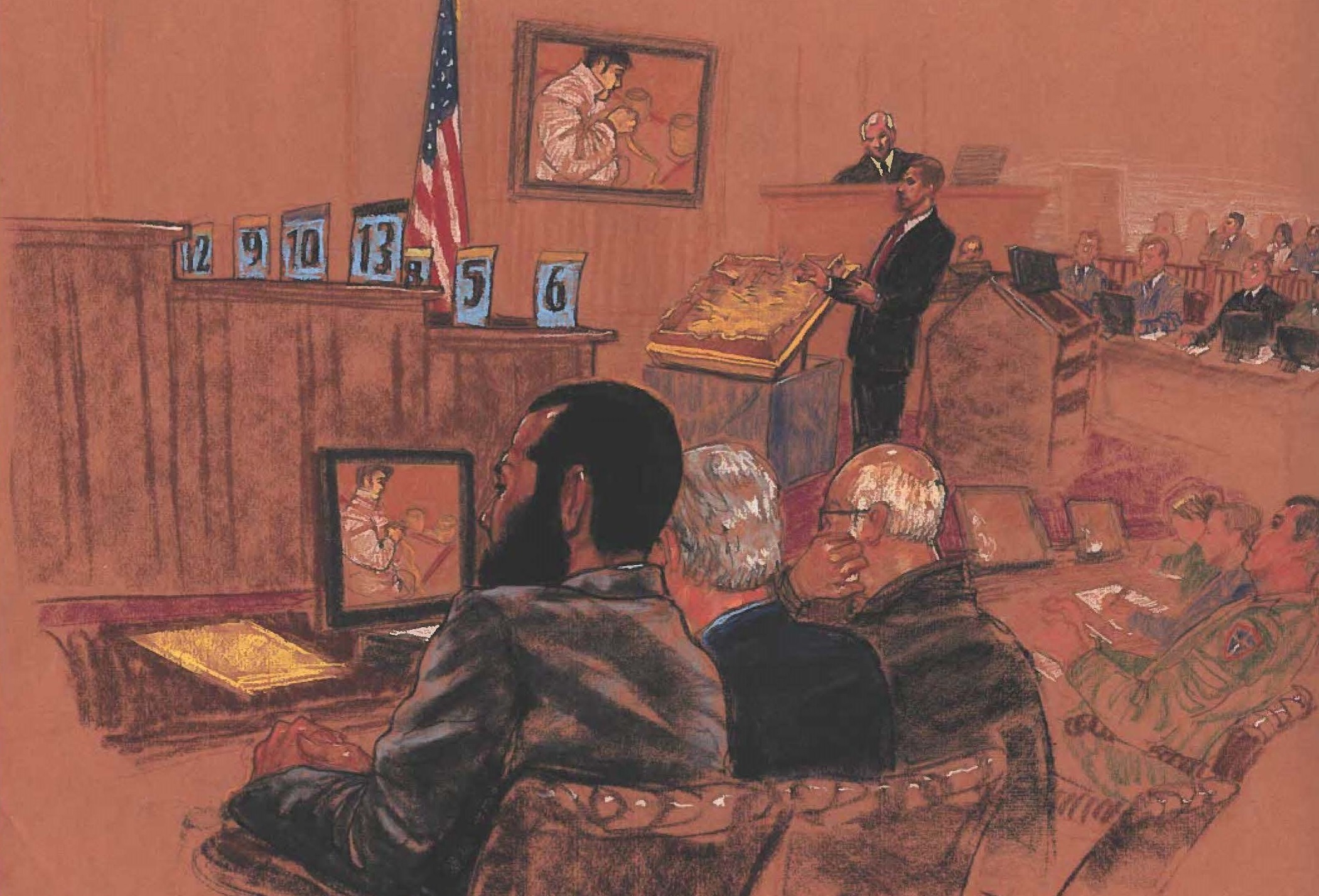

These are the issues—victims and values—that have prompted us to reconvene and try again to point the way toward an expeditious resolution of Guantánamo’s two ongoing death-penalty cases: Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) et al. and Abd al Rahim al Nashiri. Over the past two years, we have continued to observe the Guantánamo proceedings—50 of us have now spent a collective 255 days at Camp Justice—and we have grown only more frustrated by the roadblocks that thwart something as basic as a trial date. To reach the 17th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks without even knowing what year the 9/11 trial is expected to begin, after six years of pretrial jockeying and sparring, is an affront to the surviving families’ anger, pain, and right to an adjudicated outcome. It is also an affront to our system of, commitment to, and reputation for justice—at home and abroad.

Under the current statutory regime, however, there is still no mechanism for ending the procedural skirmishes, holding both sides accountable, and propelling these proceedings toward trial. As long as Guantánamo’s judges lack the will to enforce deadlines and the authority to impose meaningful consequences, the cases will not reach trial within any tenable timeframe, if ever at all. This uncertainty hurts not just the victims but everyone involved. We continue to believe that the principal recommendation of our 2016 report, Up to Speed, in which we recommend that federal judges are sent to Guantanamo——offers a pragmatic, nonpolitical solution to getting these cases on track. But we now go a step further.

Our task force is in unanimous agreement that federal judges should be sent to Guantánamo with expanded powers, including the authority to issue binding orders on discovery and, to the extent necessary, sanction parties that do not or will not comply.

This tool would be both statutory and psychological: we cannot ask judges to be more resolute if they know their orders lack teeth. To assist with the enormous burdens of discovery, the Guantánamo judges should also have the latitude to appoint a magistrate and electronic discovery specialist, just as Article III judges routinely do in complex litigation stateside. From the beginning of these proceedings, the overwhelming obstacle has been the tug-of-war over classified information related to the CIA’s Rendition, Detention, and Interrogation (RDI) program—evidence caught between the government’s legitimate interest in protecting national security and the defense’s right to investigate and defend against the charges.

With the death penalty looming over these cases, the question of what is discoverable and what isn’t has even greater ramifications. If the prosecution hopes to convict KSM and his cohorts—and carry out their executions—it will need to permit a judge to privately review documents related to the defendants’ experiences in the CIA’s secret prisons and either turn over those documents the court deems relevant or provide a satisfactory substitute, i.e., a summary or written admission of what the relevant evidence contains. If the defense, on the other hand, wishes to gain access to RDI-related evidence, it will need to establish that each discovery request is legally necessary—that the information is relevant, noncumulative, and helpful to its case and that the proffered summary or admission is inadequate. If the government, for whatever political, military, or logistical reason, won’t produce relevant discovery, or if the defense won’t tailor its requests to evidence that satisfies the standard for legal relevance, then there truly may be no end in sight. Allowing the parties to wrangle indefinitely, without establishing deadlines or levying consequences, undercuts the whole point of this process.

If these cases are to move forward, Guantánamo’s judges need to establish boundaries and enforce timetables for all parties. That could mean ending discovery and setting a trial date sooner than the defense would like, a remedy already within the court’s discretion. Or—to ensure the court’s powers are symmetrical—it could mean limiting the punishment that the prosecution is entitled to seek at sentencing, even removing the death penalty from consideration.

We take this position without passing any judgment on the merits of the death penalty or its appropriateness in these cases. Nor are we addressing the legal and moral dimensions of the RDI program. Our task force encompasses a wide range of opinion on these subjects. What we agree on is that, as a practical matter, the death penalty will never be imposed on any of these defendants unless the discovery process is expeditiously and fairly concluded. It is time that we all come to terms with the fate of these trials if the evidentiary standoff is not addressed. Again, we think that federal judges are ideally suited for deciding those questions, and we remain optimistic that narrow amendments to the Military Commissions Act, which we describe below, can equip them to propel the Guantánamo cases toward a fair and final conclusion.

The Evidentiary Stalemate

It has been 15 years now since suspected 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was captured, 11 years since he and his four codefendants were transferred to Guantánamo, and six years since their arraignment. Still, no trial date has been established, and none is on the horizon. Indeed, based on the hearing dates proposed for 2019—and the abrupt retirement of the judge, Army Col. James L. Pohl, who is stepping down September 30 after presiding over the case since 2012—there is no chance that a trial could even start until 2020 [2]. (The case against al Nashiri, the alleged USS Cole bomber, has been derailed by an alleged breach of attorney-client confidentiality—and the judge there, Air Force Col. Vance Spath, is also retiring [3]. ) While many factors have contributed to the glacial pace, from geographical isolation to the particularities of military law, the overarching obstacle is, has been, and likely will continue to be discovery: the battle over classified documents and witnesses related to the U.S. government’s treatment of the individual defendants.

The volume of sensitive information at issue is extraordinary—more data than the Library of Congress’s entire collection of printed materials. Simply collecting it all has been a herculean undertaking for the prosecution, especially since the information resides in the hands of multiple agencies, some of which do not fall under the Department of Defense’s control. Reviewing it has been an even more daunting task. The government is understandably protective of the sources and methods it employed in the worldwide pursuit of those who perpetrated the September 11 attacks. Producing these materials risks compromising classified tools; it also risks revealing details of what the defendants were subjected to in secret prisons.

For the defense, meanwhile, that RDI evidence is potentially a matter of life and death—as their treatment in detention forms the centerpiece of their efforts to avoid execution. The principles governing access to such evidence have been enshrined in decades of legal precedent. If, for instance, key materials have been intentionally destroyed, such as the videotaped waterboarding of detainees, the government may be in violation of its discovery obligations [4]. If a detainee made statements that were unlawfully coerced, such testimony (and its fruits) may be inadmissible at trial against him [5]. And if defense counsel can establish that a client has endured inhumane treatment, a jury that in its fact-finding role votes to convict may in the penalty phase view the government’s conduct as mitigating evidence—what the U.S. Supreme Court has called the “reasoned moral response” that makes capital cases different—and vote to spare his life [6]. Assuming a judge determines the evidence is relevant, noncumulative, and helpful [7], it is well established that the defense is entitled to the information it is seeking in some form; even those accused of the most barbarous acts have a right to exculpatory evidence [8]. In capital cases, it is left to the judge to decide what evidence is mitigating for purposes of the penalty phase. We note, however, that Rule for Military Commissions 1004 grants the accused “broad latitude to present evidence in … mitigation [9].”

But we also recognize that the defense counsel have met the prosecution’s rigid secrecy with broad requests and relentless objections, deluging the Military Commissions with hundreds of motions. Because each of the five 9/11 defendants has his own team of lawyers, their written pleadings and oral arguments often overlap—sometimes creating a round robin of protestations that can dominate the hearings. Together, defense counsel has sought access to the entire 6.2 million-page trove of classified documents that formed the basis for the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s study of the RDI program [10]. While the government has produced some responsive information [11], the defense continues to insist that more is required. In the first few months of 2018 alone, the defense has filed motions to compel the production of witnesses, interrogator statements, phone bills, black site locations, and information related to intelligence agency monitoring of the prison camp—to name a few examples.

The prosecution has resisted most of these efforts, arguing that the defense already has proof of what it seeks. “We have given them discovery that describes in vivid detail in many cases the treatment of the accused,” said prosecutor Jeffrey Groharing at an April 2018 hearing. “They can offer any piece of that, and we’re not going to dispute it.” The defense, in turn, has argued that the government’s case will collapse if the defense is denied its right to thoroughly investigate. “[E]very ineffective assistance of counsel case, every capital case that’s been reversed by the Supreme Court, has involved a lawyer who just took the discovery that the government gave and then didn’t do anything else,” KSM attorney David Nevin said at the same hearing. “These cases go down because lawyers don’t investigate.”

In short, even under the best of circumstances, moving these cases forward would be a challenge.

But, as currently constituted, the Military Commissions lack the tools and resources to break the impasse. That judicial vacuum allows every party to righteously express frustration. It invites each to accuse the other of gamesmanship. The longer discovery drags on, the more each side purports to claim the moral high ground for itself. Meanwhile, for the families who travel back and forth to Guantánamo in hopes of seeing justice administered, each passing year brings only more uncertainty—the prospect of trial, verdict, and finality no less elusive today than when these proceedings began.

A Renewed Call for Federal Judges

When we last endeavored to diagnose the delays plaguing Guantánamo, we coalesced around a structural, commonsense remedy that united the various viewpoints of our group: put federal judges in charge. More than ever, we think their special combination of constitutional powers, management skills, and lifetime tenure makes them ideally suited to expedite the two death-penalty cases. As we noted then, many of us have appeared in U.S. District Courts across the country and have witnessed firsthand the time-tested expertise and gravitas of the federal judiciary. We know from experience what they will and will not put up with. And unlike military judges, who report to the Pentagon, federal judges are free to call their own shots. Having no superiors, they will not be susceptible to perceptions of undue command influence [12].

We believe that people on both sides of the aisle have come to share our view.

Indeed, the families of four young Americans killed in Syria by the Islamic State have pleaded with the U.S. government not to take the recently apprehended suspects to Guantánamo. “Our first choice would be to try them in a federal criminal court, where they belong because their victims were Americans,” the parents of James Foley, Kayla Mueller, Steven Sotloff, and Peter Kassig wrote in a February op-ed. “Give them the fair trial that makes our nation great.” President Trump, who last November demanded the death penalty for Uzbek-born Sayfullo Saipov after eight people were mowed down with a rented truck in New York, recognized that Guantánamo could not deliver the “quick justice” he desired. “Would love to send the NYC terrorist to Guantanamo,” the President tweeted, “but statistically that process takes much longer than going through the Federal system [13].”

He is right, of course. The federal courts—and the independent, experienced, no-nonsense judges who preside over them—have successfully resolved hundreds of cases related to jihadist terror or national security since 9/11. To be clear, our task force is not advocating for the transfer of the Guantánamo cases to the U.S. mainland; we want federal judges to take the bench at Guantánamo. If U.S. District Judges were to bring their sound judgment to bear on the Guantánamo proceedings, we remain optimistic that they would help propel the Military Commissions to fair, final conclusions.

To that end, we previously proposed a simple amendment to Section 948j of the Military Commissions Act of 2009 (MCA), requiring the appointment of current or former U.S. District Judges for assignment to Military Commission cases. While we recognized that this revision would require congressional approval—always an ambitious proposition in this highly partisan climate—Congress’s embrace in the FY2018 defense bill of two of our more modest recommendations has encouraged us that functional, concrete remedies for Guantánamo’s on-again, off-again proceedings can bring together diverse coalitions.

Today, we not only renew our call for sending federal judges to Guantánamo but also propose equipping them with powers more commensurate with those of an Article III court.

Because Guantánamo’s military judges have lacked sufficient resources to sift through the staggering volume of contested evidence, we believe that federal judges assigned to Guantánamo should at a minimum have the statutory authority to appoint a magistrate judge to manage discovery and other pretrial matters. And, as necessary, the magistrate should have the discretion to appoint an electronic discovery specialist to help process that data.

As a group mostly of lawyers, many of us litigators, we have a keen appreciation for how our increasingly digital world has turned the discovery process into a costly, high-stakes slog through terabytes of electronically stored information (ESI). Overseeing the preservation, collection, review, and production of that evidence—while also safeguarding privileged communications—can quickly swamp and exhaust the capacity of the court. Under 28 U.S.C. § 631 et seq., U.S. District Judges are authorized to appoint magistrates to assist with those issues, and hundreds of them are currently serving as discovery experts. Magistrates establish ESI protocols for the parties; they adjudicate discovery disputes, including motions to compel and claims of spoliation; and they conduct in camera reviews of confidential information to determine whether it must be disclosed. Given the technological hurdles of searching and cataloging so much data, magistrates, in turn, often enlist the services of electronic discovery specialists.

While we do not underestimate the volume or sensitivity of the evidence in dispute at Guantánamo, we feel confident that a U.S. District Judge would inherently be better positioned to evaluate the millions of pieces of classified information that have thus far ensnared the cases in years-long discovery disputes.

If that judge were to also have the benefit of frontline discovery specialists—a standard feature of complex litigation in our federal courts—the impact on the Guantánamo proceedings would be immediate. Even if military judges remain in charge, they ought to at least be equipped with the same case-management resources that enable U.S. District Judges to efficiently administer the discovery process.

Authorize Federal Judges to Enforce a Timetable

If we are serious about breaking the Guantánamo logjam, we need to do more than send federal judges and equip them with expert help. In their own courtrooms, they enjoy the statutory authority to issue binding orders on discovery and sanction parties that do not comply—ultimately, the threat of fines, adverse jury instructions, or even termination of the case is what keeps a court’s scheduling orders from being more than mere suggestions. Without the power to set and enforce a timetable at Guantánamo, we fear that even formidable, fiercely independent U.S. District Judges might have difficulty bringing these cases up to speed.

The problem, as we see it, is that neither side is especially eager to try its case. The defense, obligated to fight for its clients’ lives, has every incentive to run out the clock. The prosecution, meanwhile, does not want the biggest mass-murder trial in the nation’s history to be overshadowed by a blow-by-blow account of the government’s own conduct. So, as if following a script, the parties repeat the same pattern month after month, year after year: the defense casting a wide net, and the government embarking on a time-consuming review of what it will and will not share.

A judge needs to intervene and assert control. Regardless of how essential or peripheral a defense motion may be, the government has faced no consequences for its inability or unwillingness to make timely productions of evidence.

The defense, likewise, has not been seriously forced to contemplate the reality that discovery must be relevant and must reach an end. A litigant in a federal court would eventually be subject to an order to show cause requiring the party to explain, justify, or prove why it should not be sanctioned for its failure to meet a particular deadline. Not at Guantánamo. Properly empowered, a federal judge would be able to call the question—conduct in camera hearings, determine relevance, establish a discovery cutoff date, and then hold everyone to that schedule.

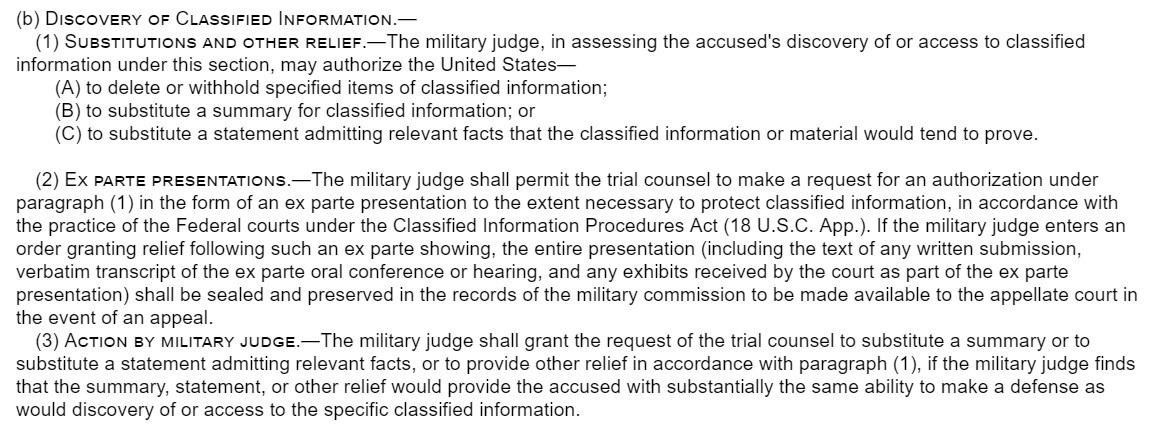

Section 949p-4(b) of the MCA provides for the “discovery of, and access to, classified information by the accused,” but as shown below, it is silent on the sort of remedial authority that would enable a judge to end the seemingly indefinite wrangling over pretrial discovery of classified material.

We therefore propose amending Section 949p-4(b) so that federal judges, if empaneled, would be granted the authority to impose discovery sanctions, including limiting the maximum penalties that may be sought at sentencing. Our suggested revision would add a fourth subsection:

By giving the court a cudgel to enforce its discovery orders, we believe that the Guantánamo proceedings would take a dramatic, and more realistic, turn. If the government can make responsive productions (or summaries/admissions in lieu of production) to valid RDI-related requests, then it should say so and be required to adhere to a strict timeframe. If, on the other hand, the government is unable or unwilling to ever produce the requested evidence in any form, then it should also be required to say so. As long as the parties circle each other, rather than chart a course to trial, the prosecution will never have an opportunity to impose a death sentence anyway. That is true regardless of the discovery sanctions available to the presiding judge. Our proposed amendment merely crystallizes and accelerates the inevitable. And it looks to the court, not the parties, to decide what is and is not relevant, and what summaries and/or admissions might supplant the need to turn over relevant classified material.

We can imagine this playing out in a few ways. Assuming the defense in the 9/11 proceedings will continue to seek as much RDI-related information as possible, we would expect the prosecution to respond, as it has previously, that it is doing its best to collect and evaluate highly sensitive documents but cannot predict when that process will be finished. Perhaps, after months or years of partial productions, discovery remains incomplete. Or perhaps, as has occurred more recently, the government deems discovery complete, but the defense argues that relevant information has been withheld. Under our proposal, a judge would have the authority to cut to the chase.

If the court determines that the prosecution still owes the defense more discovery, it would be able to demand that the government choose a date for completing production. Whatever timeline the prosecution were to offer, at least there would be a plan. Taking the prosecution at its word, the court would be able to schedule an end to discovery and get a trial date on the calendar. If the price for running afoul of those scheduling orders were the end of its capital case, the prosecution would have a strong impetus for meeting every deadline. Alternatively, if the prosecution were unable or unwilling to propose a reasonable timeline, then an amendment to Section 949p-4(b) would allow the judge to take the death penalty off the table right then and there. The prospect of such a severe sanction might inspire the prosecution to devise a schedule it can stick to. Or it might serve as a reality check: foreclosing the death penalty, streamlining the proceedings, and perhaps setting the stage for a plea agreement. Either way, empowering a judge to make that call would likely break the impasse that has kept a trial date out of reach.

Conclusion

While we believe that the recommendations described here would have an immediate effect on the Guantánamo proceedings, our proposal is not limited to the current moment. These amendments could have altered the course of the pending trials years ago, and they will remain applicable well into the future—whether for these cases or for cases not yet brought. Our task force spans a diverse range of perspectives, but we all share a commitment to the transparency and integrity of the American system of justice, which means taking steps now to construct a fair and predictable path forward. We should do so both for the victims and for our values.

The Pacific Council’s GTMO Task Force includes 23 members, all of whom have traveled to Guantánamo as official civilian observers.

GTMO Task Force Co-Chairs

Mr. Richard B. Goetz, Partner, O’Melveny & Myers LLP

Ms. Michelle M. Kezirian, Attorney at Law

GTMO Task Force

Mr. Robert R. Begland, Jr. Partner, Cox, Castle & Nicholson LLP

The Honorable Robert C. Bonner, Senior Principal, Sentinel HS Group

Dr. Lyn Boyd-Judson, Director, Levan Institute for Humanities & Ethics, USC

Mr. Joe Calabrese, Partner, Latham & Watkins LLP

Mr. Charles Gillig, Supervising Attorney, Neighborhood Legal Services

Dr. Jerrold Green, President & CEO, Pacific Council on International Policy

Ms. Carol Leslie Hamilton, Attorney, Law Office of Carol Leslie Hamilton

Ms. Perlette M. Jura, Partner, Gibson Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Mr. Michael Kaplan, Co-Partner, ARKA Properties

Mr. Victor I. King, University Legal Counsel, California State University, Los Angeles

Mr. Harry J. Leonhardt, Senior Vice President, General Counsel, Chief Compliance Officer & Corporate Secretary, Halozyme

Ms. Melanie Monestere, Trusts & Estates Attorney (retired)

Mr. John F. Nader, General Counsel, Data Society

Ms. Tara Paul, Attorney at Law, Water Practice Group, Nossaman LLP

Dr. K. Jack Riley, Vice President & Director, RAND National Security Research Division

Mr. John Stamper, Litigation Partner, O’Melveny & Myers (ret.)

Mr. Harry Stang, Senior Counsel, Bryan Cave LLP

Mr. Steven Stathatos, Attorney, Buchalter Nemer

Mr. Paul J. Tauber, Partner, Coblentz, Patch, Duffy & Bass LLP

Mr. Todd Toral, Partner, Jenner & Block LLP

Ms. Carole Wagner Vallianos, Principal, Law Offices of Carole Wagner Vallianos & President & CEO, Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute (ret.)

Staff

Mr. Jared R. Ginsburg, Litigation Associate, O’Melveny & Myers LLP

Mr. Jesse Katz, Editor, O’Melveny & Myers LLP

Ms. Ashley McKenzie, Senior Officer, Delegations, Pacific Council on International Policy

Ms. Marissa Moran, Senior Officer, Communications, Pacific Council

Mr. Justin Chapman, Officer, Communications, Pacific Council

Ms. Madison Jones, Associate, Communications, Pacific Council

Ms. Cynthia Tan provided report design. Ms. Carol Hamilton, Mr. Michael Kaplan, and Mr. Harry Leonhardt provided photos.

This report was published in September 2018. Download a printable version of this report here.

Endnotes

1. Our 2016 report, Up to Speed, urged Congress to send federal judges to Guantánamo to preside over the military trials. We also recommended that: counsel be permitted to appear by videoconference for pretrial matters; each judge be required to set a feasible trial date; surviving families be invited to provide victim impact statements without waiting until sentencing; and proceedings be broadcast or streamed for the public. The latter two ideas captured the attention of Congress, which amended the FY2018 defense appropriations bill to: (i) encourage Guantánamo’s military judges to take recorded testimony from the families of victims wishing to memorialize their losses, and (ii) order a study of the feasibility and advisability of making Military Commission hearings available for public viewing over the internet.

2. Carol Rosenberg, Army judge not planning for 9/11 trial at Guantánamo in 2019, MIAMI HERALD, June 13, 2018, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo/article213108769.html; Carol Rosenberg, Sept. 11 judge quits terror trial, names successor as he announces retirement, MIAMI HERALD, August 27, 2018, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo/article217385995.html.

3. Carol Rosenberg, Frustrated USS Cole case judge retiring from military service, MIAMI HERALD, July 5, 2018, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo/article214354414.html.

4. See Illinois v. Fisher, 540 U.S. 544, 547-48 (2004) (a failure to preserve potentially useful evidence constitutes a denial of due process if a criminal defendant can show bad faith on the part of the government) (citing Arizona v. Youngblood, 488 U.S. 51, 58 (1988)). The rules for unavailable evidence in Rule for Military Commissions (R.M.C.) 703(f)(2) are consistent with, but broader than, the due process jurisprudence related to the preservation of evidence. R.M.C. 703(f)(2) provides a “critically important to a fair trial” test.

5. See Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U.S. 278, 286 (1936) (a conviction obtained by confessions procured through the use of torture is not the commission of mere error, but of “a wrong so fundamental that it mak[es] the whole proceeding a mere pretense of a trial and renders the conviction and sentence wholly void”); Rabbani v. Obama, 656 F. Supp. 2d 45, 54 (D.D.C. 2009) (“[E]vidence that coercion, abuse or torture were used to obtain inculpatory statements from [a] defendant at any point during his detention must be produced.”) (quoting Lyons v. Oklahoma, 322 U.S. 596, 603 (1944)). See also 10 U.S.C. § 948r(a) (“No statement obtained by the use of torture or by cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment…whether or not under color of law, shall be admissible in a military commission under this chapter…”) (But a statement of the accused may be admitted in evidence in a military commission only if the military judge finds— ‘‘(1) that the totality of the circumstances renders the statement reliable and possessing sufficient probative value; and ‘‘(2) that— ‘‘(A) the statement was made incident to lawful conduct during military operations at the point of capture or during closely related active combat engagement, and the interests of justice would best be served by admission of the statement into evidence; or ‘‘(B) the statement was voluntarily given. 10 U.S.C.§948r(c)).

6. See Skipper v. South Carolina, 476 U.S. 1, 4 (1986) (a sentencer in capital cases may not refuse to consider or be precluded from considering “any relevant mitigating evidence”) (quoting Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104, 114 (1982)). See also 10 U.S.C. § 949j(b)(3) (Trial counsel in a military commission “shall…disclose to the defense the existence of evidence…that reasonably may be viewed as mitigation evidence at sentencing.”).

7. See 10 U.S.C. § 949p-4(a)(2); Rules for Military Commissions (R.M.C.) 701 and 703; see also United States v. Yunis, 867 F.2d 617, 622 (D.C. Cir. 1989).

8. See Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14, 19 (1967) (every accused defendant has a right to a robust factual record, and to obtain witnesses and evidence to present a complete defense); Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83, 87 (1963) (suppression by the prosecution of evidence favorable to an accused violates due process where the evidence is material either to guilt or to punishment).

9. See Rule for Military Commissions (R.M.C.) 1004.

10. Only the SSCI’s 500-page executive summary has been made public. The full 6,700-page report, as well as the millions of underlying operational cables, intelligence reports, internal memoranda and emails, briefing materials, interview transcripts, contracts, and other records, remains classified.

11. According to Chief Defense Counsel Brigadier General John G. Baker, the government has produced 17,269 pages of more than 6,200,000 pages of known RDI materials as of February 23, 2018.

12. While we do not express any view on the circumstances that led to the replacement of the two most recent full-time Convening Authorities—Harvey Rishikof (who was dismissed in February 2018) and Retired Marine Maj. Gen. Vaughn Ary (who resigned in March 2015)—their answerability to the Pentagon only underscores the need to appoint federal judges shielded from a chain of command.

13. On May 2, 2018, under a January 30 executive order signed by President Trump, Secretary of Defense James Mattis delivered to the White House an updated policy “governing the criteria for transfer of individuals to the detention facility at U.S. Naval Station Guantánamo Bay.” While the Pentagon has not publicly disclosed the substance of the recommendations, the subject matter does not address the pace of Guantánamo’s pending cases or provide a mechanism for moving them to trial.

About the Pacific Council

The Los Angeles-based Pacific Council on International Policy is an independent, nonpartisan organization committed to building the vast potential of the West Coast for impact on global issues, discourse, and policy. Since 1995, the Pacific Council has hosted discussion events on issues of global importance, convened task forces and working groups to address pressing policy challenges, and built a network of globally-minded members across the West Coast and the world.

The Pacific Council is governed by a Board of Directors chaired by Mr. Marc B. Nathanson, Chairman of Mapleton Investments, and Ambassador Rockwell A. Schnabel, former U.S. Ambassador to the European Union. Dr. Jerrold D. Green serves as the President and CEO. The Pacific Council is a 501c(3) non-profit organization. Its work is made possible by financial contributions and in-kind support from individuals, corporations, foundations, and other organizations.

Learn more at pacificcouncil.org.