Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1 Flowing Toxins in Bangladesh and Indonesia Richard C. Paddock, Debbie M. Price, Larry C. Price

Chapter 2China’s Dirty Pollution SecretHe GuangweiFred de Sam LazaroChapter 3India’s Contaminated Water and Poisoned LandscapeSean GallagherChapter 4Fire and SmokeMakenzie Huber, Nathalie Bertrams, Ingrid Gercama, Michelle Nijhuis, Lynn Johnson

Chapter 5Polish Gold: Coal’s Deadly TollBeth Gardiner

Chapter 6Legacy of LeadCaitlin Cotter, Yolanda Escobar, Richard C. Paddock, Larry C. Price

Chapter 7Pollution in the U.S.Debbie M. Price, Larry C. PriceResourcesContributorsCredits

Introduction

It affects the air we breathe, the water we drink, the soil that helps produce the food we eat. Pollution is everywhere.

Pulitzer Center grantees circumnavigated the globe to study pollution—its risks, the health implications, potential remedies, and means of prevention. Their work has been published in a wide range of outlets: Undark, National Geographic, Yale Environment 360, China Dialogue, PBS NewsHour, Bloomberg Businessweek, TakePart, The Guardian, VersPers, The New York Times, and Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health Magazine.

Toxic Planet brings together their stories, brilliant and heart-wrenching photography, and video to form a more complete picture of the challenges the world faces and of the profound impact of toxic chemicals on all humans, most noticeably on babies and children. Many of the portraits of families are intimate and deeply troubling.

Documentary photographer Larry C. Price, journalist Debbie M. Price, and foreign correspondent Richard C. Paddock report from Southeast Asia on the effects of pollution from tanneries, the textile industry, and small-scale gold mining. Men, women, and children are exposed to the chemicals in untreated sewage and solid waste from factories and to the mercury vapors released in artisanal mines. They suffer the health consequences, and many die young.

In China, He Guangwei, investigative reporter for the Chinese newspaper The Times Weekly, exposes the threat of soil pollution to health, a subject often overlooked by the media. In some industrial areas the soil has become so contaminated that local farmers will not eat the crops they grow. Regional cancer epidemics have occurred giving rise to “cancer villages”—as many as 450 across China, civil society experts say. In a PBS NewsHour video, Fred de Sam Lazaro, director of the Under-Told Stories Project, focuses on air pollution in China—and how an environmental group is working to hold companies accountable for sustainable manufacturing and sourcing.

Photojournalist Sean Gallagher travels to India to create visual stories of the damage caused by pesticides, chemicals used in the textile and leather industries, and the recycling of electronic waste. Here too “cancer villages” are a common phenomenon where toxic chemicals are most prevalent.

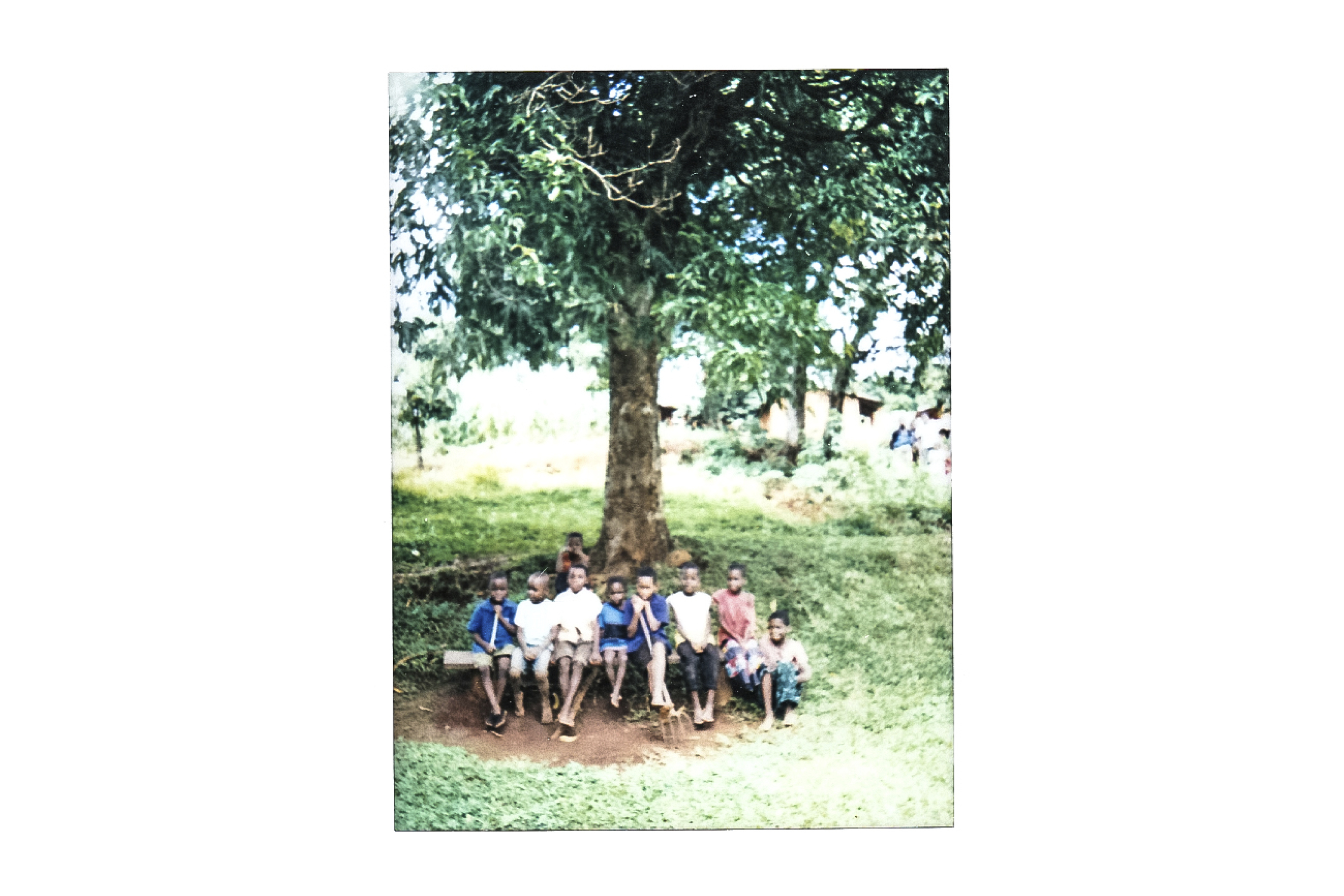

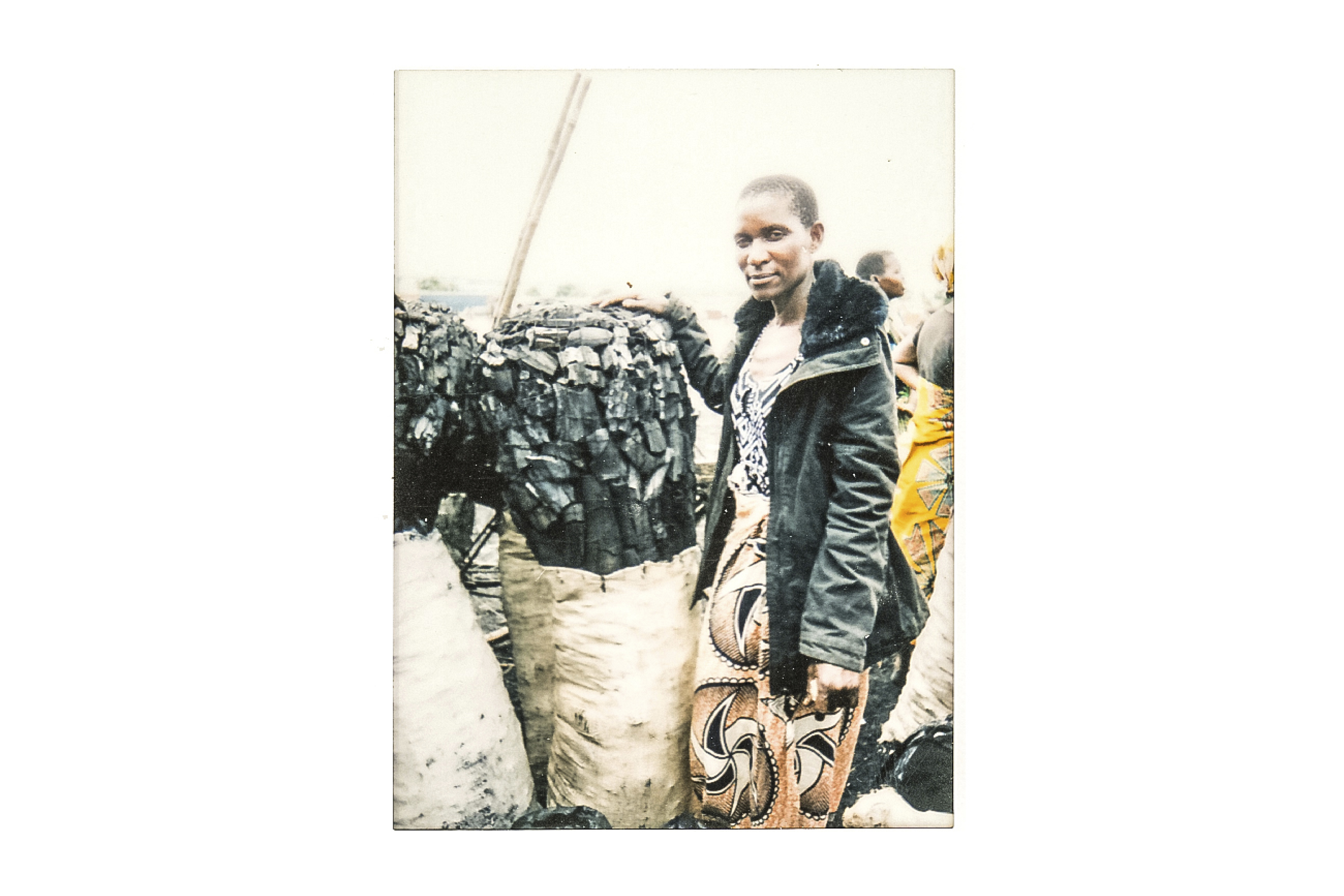

Reporting from the Dominican Republic, Malawi, and Guatemala, Makenzie Huber, Nathalie Bertrams, Ingrid Gercama, Michelle Nijhuis, and Lynn Johnson look at cookstoves and show how wood, coal, charcoal, and dung cause severe health effects. An open fire puts children at risk of burns—and every year cooking smoke results in the death of 4.3 million people a year. That’s more than HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria combined‚ and yet the risk receives far less attention from the public health community.

Environmental journalist Beth Gardiner discusses coal’s “deadly toll” in Poland, a country dependent on coal for 90 percent of its electricity. Its use produces air pollution, soot particles, and carcinogens that force the elderly and children to stay indoors.

Ceramic tile makers in Ecuador, rock crushers in Zambia, and battery recyclers in Indonesia pay a heavy price. As Caitlin Cotter, Yolanda Escobar, Larry C. Price, and Richard C. Paddock report, their work puts them and their families at risk, exposing them to lead that can have a devastating effect on the body, including the nervous system and brain development.

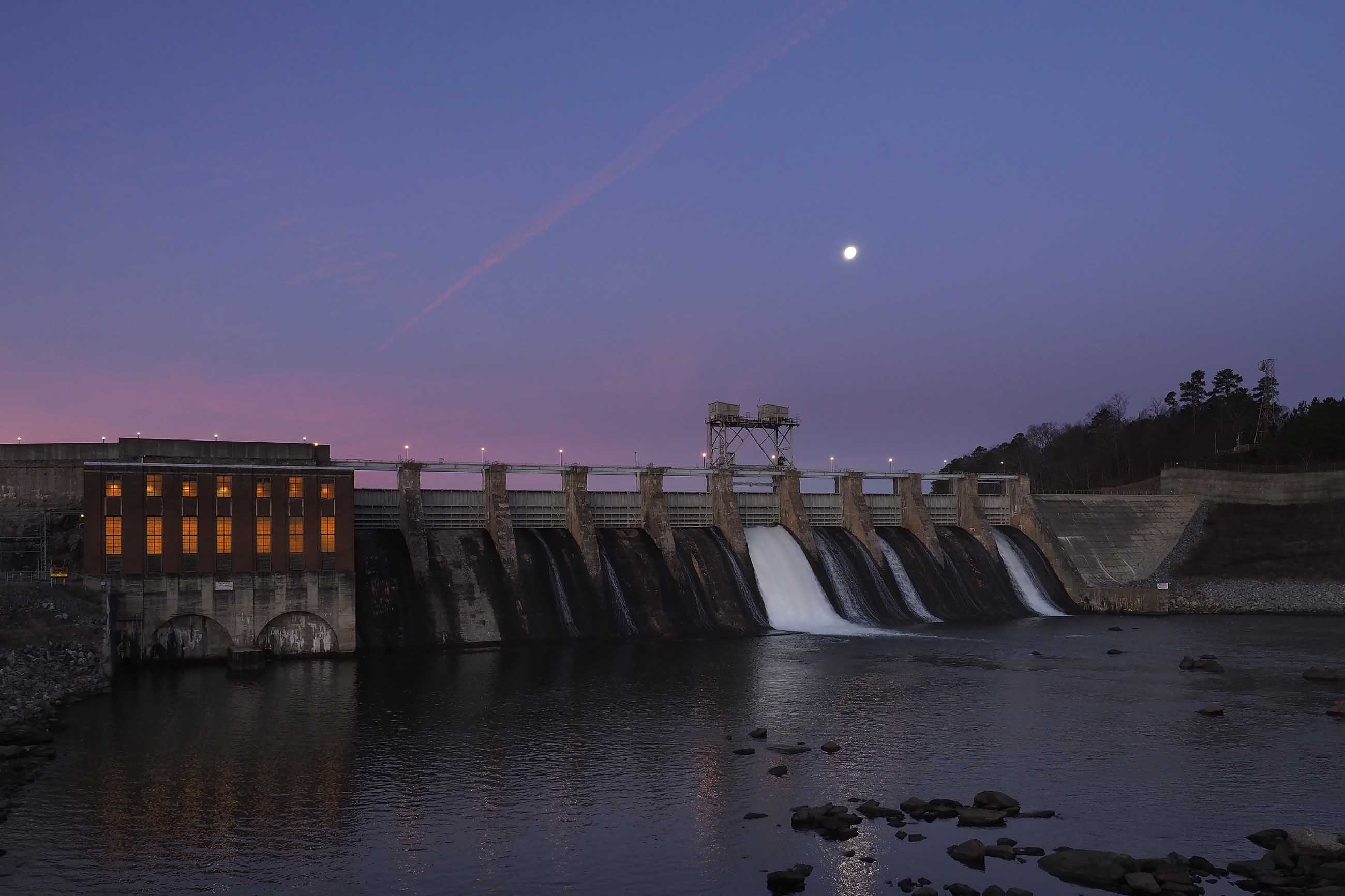

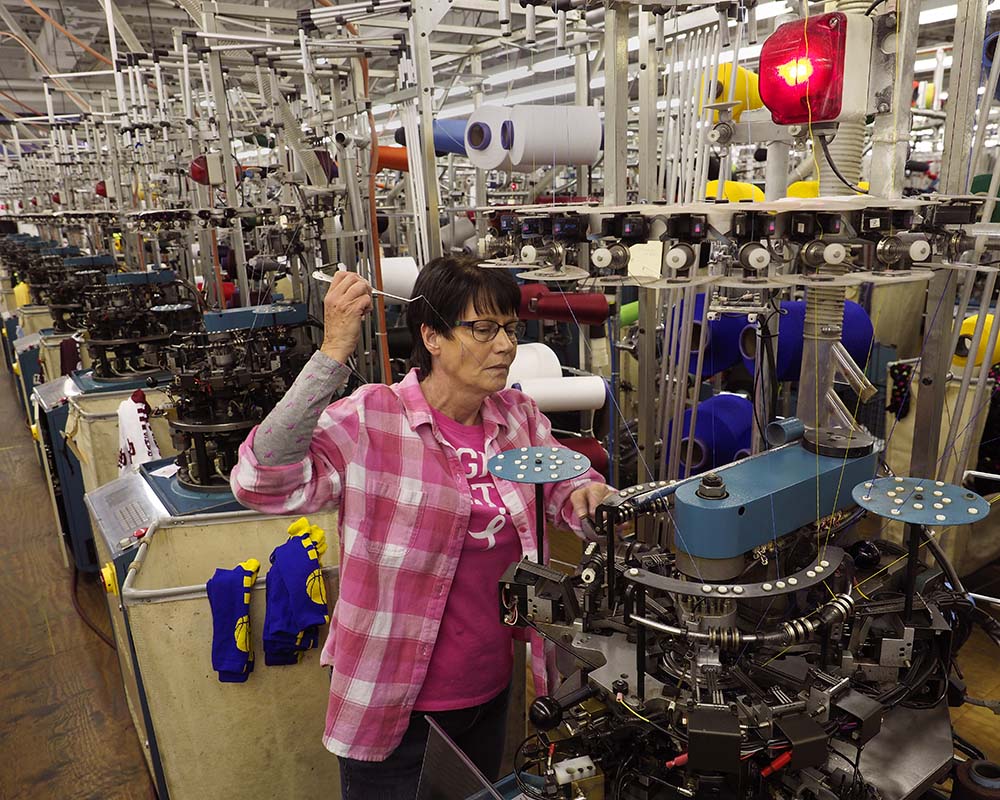

Debbie M. Price and Larry C. Price take us to the United States as they examine the resurgence of Gloversville, New York, the former leather capital of the world. New forms of processing are in place resulting in far less toxicity. The same is true for the textile industry in North Carolina. A greater demand for “Made in America,” rising wages in China, and higher shipping charges have led to an increase in textile production at home—with the added dividend of an industry that is today more environmentally and socially conscious.

Toxic Planet highlights the health risks and challenges we face as well as possible solutions—providing hope for change in government policies, better working conditions, waste treatment programs, and river clean-up projects. Innovations that are making a difference include solar ovens, improved cookstoves that are more efficient and also less toxic, the development of genetically modified crops that produce chemicals to kill pests, and more effective effluent treatment plants. New environmental awareness campaigns may well lead to behavior change.

The Pulitzer Center grantees, whose work is featured here, give voice to scientists, engineers, economists, politicians, factory workers, miners, and activists. They ask what role can we, as consumers, play. What is the footprint we leave behind? How do we clean up the damage we’ve caused?

Toxic Planet is a call to action—and a reminder that if we are to act it must be now.

Kem Knapp Sawyer

Map of the World

Countries highlighted in this map are included in the e-book.

Chapter 1: Flowing Toxins in Southeast Asia

Photographer and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Larry C. Price and journalist Debbie M. Price introduce us to Hazaribagh, home to Bangladesh’s tannery industry: “The stench of the place smacked us in the face: rotting animal flesh, garbage, raw sewage, auto exhaust and acrid chemicals mingled together in a nauseating stew.” The city’s tanneries pump almost 5.8 million gallons of untreated effluent a day into open canals and generate more than 100 tons of solid waste in the form of raw hide scraps, flesh, and fat.

This chapter examines the pollution produced by tanneries in both Bangladesh and India and by the textile industry in Indonesia. Clothing factories in West Java have helped make the Citarum, which provides drinking water for more than 25 million people, one of the world’s most contaminated rivers. Some parts of the river are now “thick and dark as motor oil.” Also in Indonesia, foreign correspondent Richard C. Paddock and Larry C. Price document small-scale gold mining—an industry that produces $5 billion in gold a year, while releasing hundreds of tons of mercury into the water, soil, and air. Mercury poisoning, although difficult to diagnose, can cause severe birth defects and developmental delays in children.

Their reporting illuminates the complex problem of reforming these industries and restoring waterways that have been polluted for decades. Is change imminent?

Recent court decisions in Bangladesh, India, and Indonesia—together with pressure from American and European companies—have given activists hope for better working conditions, waste treatment programs, and river cleanup projects.

-R.K

Skin Deep: Feeding the Global Lust for Leather in Bangladesh

Debbie M. Price. Images by Larry C. Price.February 2017

As 2016 marched to a close, rumors and panic raced through the leather tanneries in the Hazaribagh neighborhood of Dhaka. After years of extensions and delays, the government would finally require the remaining 150 or so tanneries in this historically unregulated and polluted corner of Bangladesh’s capital city to shutter. Any tanners who wanted to remain in business would have to relocate to a planned industrial park in Savar, a community roughly 14 miles away.Authorities vowed to cut off utilities, blockade roads to prevent shipments of raw hides from entering Hazaribagh, go door-to-door to roust disobedient tanners, and revoke the licenses of all who defied their orders.

Days before the deadline, Mohammad Shohorab Hossain Jhony, a director of FFM Leather Complex, scrolled through his smartphone to show a friend photographs of his new facility under construction at the Tannery Estate Dhaka at Savar—a concrete slab, two walls, no roof, just 40 percent completed. Weighing the loss of his license against six months of lost production while the Savar building was finished, Jhony said he would be forced to close, at least temporarily, putting 70 to 100 men out of work. If they chose not to follow him to the industrial park, a six-hour round-trip commute in bumper-to-bumper Dhaka traffic, some might never return to FFM.

On December 30, 2016, the blockades went up, and then on January 1 the government stood down, extending the deadline again by telling the tanners they would have to stop processing wet animal hides on January 31, without exception. They would have until March 31 to move their entire operations. “This is the final decision,” Mosharraf Hossain Bhuiyan, the Bangladesh industries secretary, told the local press.

So it has gone for years, as the Bangladesh government attempts, in fits and starts, to make good on promises to clean up its leather processing industry and propel what is, in effect, a 19th-century operation into the 21st century.

About 90 percent of Bangladesh’s leather is tanned in Hazaribagh. And the country’s economy depends heavily upon leather and the manufacture of leather goods—which explains in no small measure the government’s reluctance to crack down on polluters. In 2015 and 2016, Bangladesh produced about $1.5 billion in leather and leather goods, most of it exported, according to the Bangladesh Board of Investment.

Leather and leather goods represent the country’s second largest export, after garments. Turmoil in Hazaribagh threatens to upend the country’s efforts to increase its tiny share of the more than $200 billion global leather market.

Should that come to pass, it would be just one more step in a long journey for the tanning industry, which has spent decades hopscotching across the globe, assiduously fleeing regulation and rising labor costs and leaving long-lasting toxic footprints at each stop.

So far, fewer than 40 of Hazaribagh’s tanneries have moved to Savar, and an abrupt shutdown of the remaining tanneries could put thousands of people instantly out of work. That would almost certainly provoke civil unrest and deal a major blow to the country’s leather industry—just when the government is trying to grow exports and fend off competition from China and Vietnam. On the flip side, as The Dhaka Tribune reported in September 2016 negative publicity about conditions in Hazaribagh is scaring away international buyers and driving down finished leather exports, which fell by 30 percent last year, according to government figures.

In fact, the international shaming of Bangladesh’s leather industry could succeed where government decrees have failed. It has been seven years since the Bangladesh High Court ordered the government to move or close Hazaribagh’s tanneries. Almost 14 years have passed since the Bangladeshi government announced plans to develop an industrial park with a shared effluent treatment plant for tanneries. Yet

Hazaribagh remains arguably one of the most intensely polluted places on the planet.

By official estimates, the tanneries of Hazaribagh pump almost 5.8 million gallons of untreated effluent a day into open canals that pour into the Buriganga River and generate more than 100 tons of solid waste in the form of raw hide scraps, flesh, and fat. The tannery effluent, laced with chromium (III) sulfate, sulfuric acid, salts, lime, surfactants, degreasers, ammonium sulfate, and many other chemicals, contaminates the water and river bed and kills aquatic life. Numerous studies have found highly elevated levels of chromium and other chemicals in the soil and water of Hazaribagh. For years, government officials, citing the planned move to Savar, have openly admitted that they do not enforce environmental regulations in the district.

The Buriganga itself, once the main source of drinking water for Dhaka, has become so polluted by tannery and other industrial and human wastes that it is widely regarded as unsafe for human use—even as the greater metropolitan area of more than 17 million people struggles with episodic droughts and depleted groundwater supplies. Leather scraps accumulate in rotting heaps six feet high along the canals.

Chickens—a staple of the Bangladeshi diet—are often fed tannery scraps, and Dhaka University chemistry professor Mohammad Abul Hossain, Ph.D., and his colleagues have found high levels of chromium in the bones, brain, and muscle of the birds. Residents who ate 250 grams of chicken a day, about a quarter of a bird, would consume up to four times the recommended amount of dietary chromium, according to Hossain’s research. Chicken-feed producers officially ceased using tannery scraps after his report came out, but unregistered factories abound and locals still boil the waste and feed it to their household poultry, he says.

While chromium (III), also known as trivalent chromium, is far less dangerous than the carcinogenic compound chromium (VI), or hexavalent chromium, long-term and direct exposure to chromium (III) is known to cause serious skin and respiratory irritation. Hossain and others have also found that when leather scraps are exposed to high heat under certain conditions, some of the trivalent chromium converts to hexavalent chromium, posing more serious risks.

Chrome tanning is the leading method used worldwide, and most argue that chromium (III) sulfate can be used safely as long as workers are properly protected and the factory effluent is captured and treated. But many of the more than 30 chemicals used in tanning animal hides also have their own dangers. Some of the workers photographed had blackened and peeling skin on their hands and feet from long exposure to tanning chemicals. Others coughed almost constantly.

In Hazaribagh, worker protections are scarce and child labor is common, as the nonprofit group Human Rights Watch documented in an extensive 2012 report.

“Tanning is an industry that is extremely hazardous, which means two broad things in terms of labor,” says Richard Pearshouse, the author of the Human Rights Watch report and a frequent visitor to Hazaribagh. “You need to take reasonable steps to protect your workers—protective equipment, masks, gloves, aprons, to protect against chemical burns—and you do not employ children.”

A few of the workers photographed for this essay did wear boots and gloves. Most, though, worked with their bare hands, stood barefoot in chemicals on the tannery floor, waded into tanks filled with tanning solutions, and climbed into drums to retrieve the wet blue leather, literally bathing themselves in a soup of caustic and potentially toxic chemicals. Young boys carried water and hides and operated stretching machines, while smaller children tended pieces of leather soaking in open vats.

“If they don’t address the problems of worker safety and working conditions and child labor, they are just moving the problem from Hazaribagh to Savar,” says Pearshouse.The turmoil today in Hazaribagh is reminiscent of the situation in Kolkata, India, in the 1990s and of the collapse of the century-old tannery industry in Gloversville, New York, in the 1980s. In Gloversville, competition from cheaper labor coupled with tougher local and federal environmental laws forced one tannery after another out of business. The town and surrounding county have spent the decades since rebuilding the economy and cleaning up pollution the factories left behind.

In Kolkata, the Supreme Court of India ordered all tanners out of the city almost two decades ago. In response, the government built the Kolkata Leather Complex with a common effluent treatment plant. About 300 tanneries located in the complex today produce about 25 percent of India’s leather. Environmental controls are better at the industrial park than at the old Kolkata tanneries. Labor oversight, authorities say, also has improved, although horrific accidents still happen. In December 2015, three workers died from inhaling toxic fumes while cleaning out a holding tank without protective gear.

India, one of the world’s leather giants, exported $5.92 billion in leather and leather goods between 2015 and 2016, with about 14 percent of that going to the United States, according to the India Brand Equity Foundation. Roughly 60 to 70 percent of the country’s leather and leather goods is produced in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, where tanneries still look a lot like those in Hazaribagh.

Here women—wrapped in plastic to protect their brightly colored saris—sit or stand for hours plucking hair from softened goat skins stretched over frames, while the men tend the drums filled with hides and chemicals.

Despite efforts at reform, human rights groups continue to find widespread pollution and horrendous working conditions in the tanneries of Tamil Nadu. A joint study in 2015 by Norwegian and Indian organizations found workers, particularly migrants, unprotected and unaware of the hazards. In January 2015, 10 migrant workers were killed where they slept when a wall of a Ranipet tannery collapsed and released a torrent of slurry upon them. It was one of India’s most horrific tannery accidents.

Tamil Nadu also is beset with serious environmental contamination caused in part by abandoned tanneries and factories that made chemicals for the leather-processing industry. More than 20 years after the Tamil Nadu Chromates & Chemicals Ltd. factory closed, the grounds of the abandoned factory on the SIPCOT Industrial Complex outside Ranipet remain covered in 165,000 tons of chromium-bearing waste. Government agencies and international environmental groups have been studying the site and developing remediation plans since the late 1990s. Meanwhile, the bright-yellow runoff has contaminated land 1.5 miles south of the plant with hexavalent chromium, a 2010 study shows.

Bangladesh authorities, too, will face a monumental environmental cleanup when the tanners finally leave Hazaribagh. Mizanur Rahman, treasurer of the Bangladesh Tanners Association and executive director of Samota Leather Complex, said the association and tanners will contribute to the efforts to restore Hazaribagh out of “social responsibility.”

So far, though, the government has yet to announce official plans to address lingering pollution. Pearshouse says that when he asked a government official last year about remediation plans, the official told him a cleanup would not be necessary because “all the pollution would be washed away.”

“They have no idea who would actually fund [a cleanup],” Pearshouse adds.

Shipping records compiled by Datamyne, a provider of international trade data, provide a snapshot of Bangladesh exports to the United States. From January through the end of October 2016, Datamyne reported $52.24 million worth of individual shipments of leather and leather goods to companies in the United States. Very little of that was processed leather shipped directly from Hazaribagh tanneries. Most of the shipments contained finished leather goods bound for major U.S. and European fashion retailers. There is virtually no way for consumers to know where the leather in those shoes, purses, or belts came from unless the companies themselves reveal their supply chains.

According to the Datamyne records, more than a dozen fashion and shoe companies imported products made in Bangladesh through November 2016. The largest of these include Michael Kors, Timberland, Hugo Boss, C & J Clark America, Puma, and the Gap Inc. brand Banana Republic.

Timberland, Hugo Boss, Puma, Clarks, and Gap each told Undark that their companies do not use leather from Hazaribagh in their products manufactured in Bangladesh. Timberland provided the most explicit information, including photographs of shipping cartons and invoices, to verify that the leather used in its products made in Bangladesh came from a Vietnamese tannery rated “gold” by the Leather Working Group, an international association that audits tanneries and promotes best practices for the industry. A company spokeswoman said that Timberland employs numerous checks and balances to ensure the integrity of its supply chain and audits its manufacturing partners and suppliers at least annually to ensure that the companies treat their workers fairly and meet the company’s standards for environmental quality.

“To ensure the integrity of our products and brand, we have to be vigilant about our leather supply chain. Not to mention, of course, it’s the right thing to do,” said Colleen Vien, the company’s sustainability director. “One way we ensure that we are sourcing the best leathers, in terms of quality as well as sound manufacturing practices, is only using tanneries that are rated gold or silver by the Leather Working Group. No tanneries in Bangladesh today meet our stringent standards.”

Puma said that 90 percent of its leather comes from tanneries rated by the Leather Working Group. The Bangladesh factory that makes shoes for Puma was last audited in November 2016, the company said. “We are aware of the challenges related to leather production in Bangladesh,” they said. “Therefore Puma does not source any leather from Bangladesh and as far as we are aware, our suppliers are also not sourcing any leather from Bangladesh.”

Clarks, a founding member of the Leather Working Group, said the company conducts “social audits” at tanneries supplying 80 percent of the leather for its products, and that it sources more than 75 percent of its leather from LWG-rated tanneries. About 20 percent of the leather comes from tanneries in regions considered at low risk for social abuses, the company said, and tanneries that have not achieved LWG medal-rated status are closely monitored to ensure that they are making progress toward meeting the higher standards.“Clarks has never specified leather from tanneries in Hazaribagh,” wrote Anthea Carter, the company’s global head of corporate responsibility, in an email. “Prior to 2013 the Clarks business sourced a small proportion of footwear from Bangladesh through agents. Due to the commercial arrangements with those agents Clarks did not specify or have visibility of the sources of the leather used in that production. From the information available, we have not found any links to sourcing from Hazaribagh tanneries prior to 2013.”Michael Kors, which, according to Datamyne, received more than 200 shipments from Bangladesh factories in 2016, did not respond to repeated telephone and emailed requests to discuss its leather supply chain.

Dozens of companies now have statements on their websites espousing support for ethical sourcing, human rights, and sustainable manufacturing processes. But few disclose detailed information about their suppliers. As conditions in Hazaribagh and other tanning centers of the world become more well known, consumers are asking whether the leather in their boots or bags was produced by tanneries that pollute and expose workers to hazardous conditions. Pearshouse maintains that companies have an obligation to answer those questions.

“If there are large companies that are importing from Bangladesh, the question of ‘where did your leather come from’ must be known,” says Pearshouse. “It’s no longer adequate for a company to say ‘We don’t know,’ or ‘We don’t say.’”

“Leather companies should be on notice,” he adds, “that if they’re importing from Bangladesh, this is the most notorious tanning area in the world.”

[This story was published in Undark on February 21, 2017. Reprinted with permission.]

Worse for Wear: Indonesia’s Textile Boom

Debbie M. Price. Images by Larry C. Price.February 2017

With the first light, men in long boats are on the Upper Citarum River, filling their hulls with bottles, cans, and bits of broken plastic—anything that can be recycled for a few rupiahs. Everything anyone might throw away is here.Smashed styrofoam coolers, broken toys, clothes, food containers, a deflated soccer ball, even car batteries and metal tools, buoyed by the bits of plastic below, float along on the current. At bends in the river, the detritus coalesces into mats of trash, tight and strong enough for a man to walk across. The water itself is as thick and dark as motor oil, coursing with sewage, agricultural runoff, and chemicals flushed into the river by the factories that line its banks.

It was not always this way on the Citarum—routinely named one of the world’s most polluted waterways. Old-timers tell of a healthy river full of fish until the late 1970s when Indonesia’s manufacturing sector—animated in large part by textile producers and other companies fleeing rising labor costs and environmental regulations in West—began to grow and dump their effluent into the water. With the boom came a deluge of factory workers, which quickly overwhelmed municipal waste disposal systems, further stressing the river.

Today, Indonesia ranks among the top 10 textile and apparel producing countries in the world, with more than $12.7 billion in exports, including $3.96 billion to the United States in 2014, according to World Integrated Trade Solution, a trade database of the World Bank. Three million people work in the garment and textile industries, according to Indonesia Investments, an investors’ news service that covers the country’s economy.

For residents of the West Java province near Bandung, this economic growth has come at a steep price with the ruin of the Upper Citarum River and the destruction of rice fields contaminated with heavy metals in industrial effluent. Now, a recent Indonesian court ruling, if upheld, could give environmentalists a small victory in the fight to clean up the Citarum River—and at the same time, possibly imperil thousands of jobs. It is a story that has played out time and again around the world, from the Hazaribagh neighborhood of Dhaka, Bangladesh, to Gloversville, New York, as environmental regulations catch up with polluting industries.

In December 2015, two local community organizations, Pawapeling and WALHI (Indonesian Forum for the Environment), with the support of Greenpeace Southeast Asia Indonesia, sued the Sumedang Regency government and three factories permitted to dump into the Cikijing River, a tributary of the Citarum. The named plaintiffs alleged that the government had not monitored the factories’ discharge and had failed to conduct environmental impact studies before issuing the wastewater permits. Greenpeace and Padjadjaran University’s Institute of Ecology also released a report in April 2016, one month before the court ruling, in which they alleged that industrial wastewater used for irrigation had contaminated 2,300 acres of rice fields with heavy metals, and caused economic losses of about $866 million over two decades.

The Bandung court concurred with the plaintiffs’ arguments and ordered the Sumedang district government to “suspend, revoke, and cancel” wastewater discharge permits for PT Kahatex, PT Five Star Textile, and PT Insansandang Internusa, the three named textile factories. “It is clear that they violated the principles of good governance by granting those companies wastewater permits,” the plaintiffs’ attorney Agus Rasyid said of the Sumedang Regency’s failure to monitor wastewater permits.

In October 2016, the Jakarta High Court upheld the lower court ruling. The defendants appealed that decision to the Indonesian Supreme Court in December. “This indicates that there are judges who still have a conscience,” said Anang Sudarna of the West Java Environmental Agency. “We all know that if they had to comply with standards of waste treatment,” he added, “we wouldn’t see today’s destruction to the rivers and fields.”

Dwi Widi Nugroho, the lead lawyer for Kahatex, said that his client, which manufactures polyester fibers, yarn, fabrics, and garments, spends $451,000 a month to successfully remove chemicals from its wastewater. The three companies, Nugroho said, feel that they have been unfairly singled out and penalized for the actions of dozens of other upstream factories, which pump untreated effluent into the river. Both lower courts rejected these arguments, Nugroho said.

Losing the wastewater permit, he said, would be a death sentence for Kahatex, which by his estimate employs 90,000 people and sources 60 to 70 percent of its raw materials from smaller factories in West Java. “If we lose, of course we will comply with the court decision and close down,” he said. “Then the government must think about this and take care of these tens of thousands of workers.”

Environmentalists dismiss talk of closure and mass firings as scare tactics. Ahmad Ashov Birry, a toxic campaigner with Greenpeace, said that their hope is that the court ruling, if upheld, will establish a precedent. “We could ask for the government to repeal all discharge permits,” Birry said. “That’s the idea actually. We start small.”

It’s true that the Indonesian court ruling could give environmentalists the ammunition they need to force government and industry to develop and enforce effective wastewater treatment standards for the textile and apparel industry throughout Indonesia. And this, in turn, could threaten the livelihoods of thousands of people who live along its banks—even as the Indonesian textile industry is facing increased competition from China and other emerging markets in Southeast Asia.

By some estimates, there are about 2,000 industrial and manufacturing facilities in the Citarum River basin, including at least 200 textile and apparel factories near Bandung. For decades, the government has permitted factories to flush wastewater into the river, provided the effluent does not contain any of about four dozen banned industrial chemicals. Stricter wastewater discharge standards and enforcement likely would force smaller companies to close.

Factory effluent is not the only contaminant pouring into the Citarum, which irrigates crops and provides drinking water for more than 25 million people, including residents of the greater Jakarta region. A 2013 Asian Development Bank report found that most of the Upper Citarum River’s water quality parameters were far outside allowable limits. Fecal coliform bacteria—likely from manure fertilizer and sewage—was 5,000 times the mandatory limit in some locations. Municipal sewage systems and solid waste disposal in communities along the Citarum are woefully inadequate and funds to modernize are scarce.

The Asian Development Bank approved a $500 million, multi-year loan in 2008 as part of a long-term effort to restore the river. ADB funds have supported several river improvement projects, including a re-engineered canal in Bekasi to improve water quality for the greater Jakarta area. But in West Java, efforts to address the massive pollution have been sporadic at best. The Indonesian government has proposed filing civil suits against polluters, admitting that criminal prosecutions have been ineffective. Local officials have taken baby steps to curb trash.

Bandung Mayor Ridwan Kamil has imposed a ban on styrofoam packaging for all food sold in the city. Berita, the official website of the West Java Province, announced in October that the government would form a task force to work with more than 300 known polluters in Bandung to help them remediate waste and implement water treatment facilities. At a 2015 festival highlighting a four-year cleanup of the Citarum, West Java Vice Gov. Deddy Mizwar admonished the crowd, “Perhaps we no longer need the Citarum, so we make it as a waste bin and toilet stool.”

Greenpeace, for its part, is keeping up its Detox campaign to pressure the fashion industry to stop using hazardous chemicals and sourcing from polluting factories. The group’s 2013 “Toxic Threads” report blasted some of fashion’s biggest names for buying clothing from a company that owns a factory it accused of pumping untreated effluent into the Citarum. The environmental group said that it found nonylphenol (NP), nonylphenol ethoxylates (NPEs), which are used as detergents and surfactants, tributyl phosphate (TBP), antimony, which is a metalloid used in polyester manufacture, and wastewater with a pH of 14—high enough to burn the skin—from the outflow spouts at the PT Gistex Textile Division factory on the Citarum near Bandung.The report, which publicly detailed the textile chemicals in Citarum River factory effluent propelled Greenpeace to the forefront of the fight to clean up the river.

Several of the companies named in the organization’s report are members of Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals, an international group of clothing and footwear brands that have pledged to eliminate hazardous chemicals from their products by 2020. And most have sustainability statements on their websites. A few of the companies named in the Greenpeace report also still source clothing from one of the Gistex Group’s Indonesian factories, according to Datamyne, a Miami-based firm that collects global trade data for market research records.

Gap Inc. and its brands, Old Navy and Banana Republic, received well over 100 shipments in 2016 at locations throughout the U.S. from a Gistex-owned facility, according to records compiled by Datamyne. In response to questions from Undark, a Gap spokeswoman provided a version of a statement that the company has issued on occasion since Greenpeace’s original 2013 report. The statement acknowledged that the company sources from PT Gistex Garmen, which is owned by the PT Gistex Group, but asserted that the company “does not source” from the Gistex facility near Bandung that was singled out by Greenpeace. Gap has also “reiterated to the Gistex Group the importance of adherence to our Code of Vendor Conduct, including provisions regarding environmental health and safety and chemical restrictions,” the statement said. The company did not respond to specific questions about how it ensures that its suppliers are adhering to its conduct codes.

Puma, another company named in the 2013 Greenpeace report, also confirmed that PT Gistex Garmen is an active supplier. Puma said its most recent audit of Gistex was in April 2016.

“All direct Puma suppliers are regularly audited for social and basic environmental compliance through the Puma Sustainability department. These audits contain checks on the relevant environmental permissions as well as proper treatment of wastewater and waste,” the company said. Puma also said that it regularly asks all its suppliers with wet processing facilities to perform wastewater tests and publish the results through the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, a Chinese non-governmental organization.

“We have just started expanding our audits into the core material and component suppliers as we recognize that improvements are necessary,” Puma said. “This expansion into the lower tiers of the supply chain is a long-term effort.”

On its website, Gistex promotes its “Go Green” program and says that the company built a water recycling program in 2012 and in 2015 received certifications and met standards established by the International Organization for Standardization for quality and environmental management. With the certifications as a foundation, PT Gistex said it hopes “to continue with improvements in all areas,” according to a statement on the company’s website.

Several American and European companies also source from PT Kahatex, according to Datamyne. None of those companies contacted by Undark responded to interview requests.

People’s health and lives depend on companies fulfilling their commitments and cleaning up their supply chains, Birry wrote in a blog post hailing the court ruling against the factories.

“Millions depend on the health of Indonesia’s rivers, water, and land,” he added. “We won’t stop fighting.”

[This story was published in Undark on February 23, 2017. Reprinted with permission.]

The Toxic Toll of Indonesia’s Gold

By Richard C. Paddock. Images by Larry C. Price.May 2016

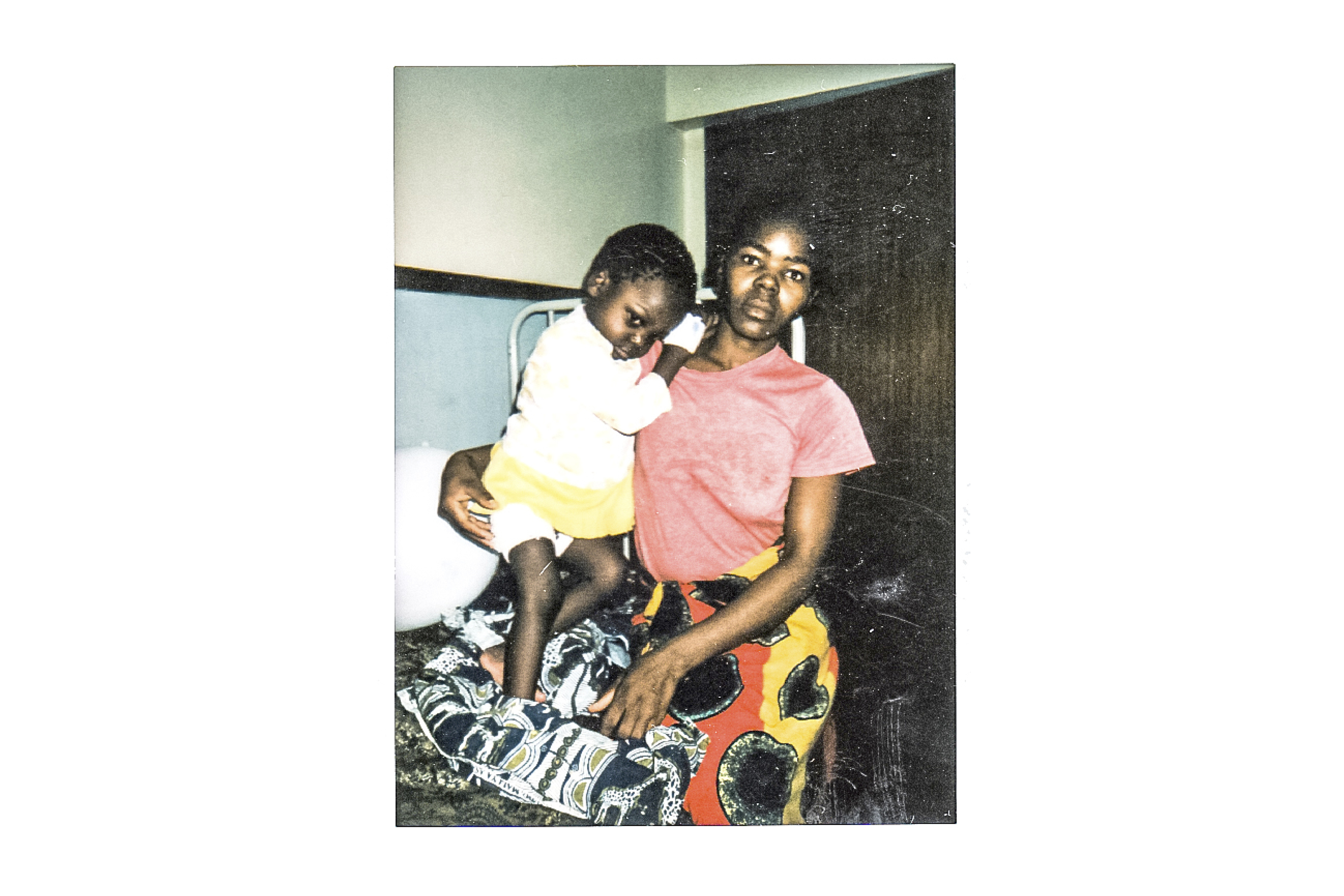

JERENGJENG, Indonesia—Ipan is 16 months old and suffering his third seizure of the morning. His head is too large for his body and his legs are as thin as sticks. He arches his back, and his limbs stiffen. He cries out in pain.

His mother, Fatimah, tries to comfort Ipan but there’s not much she can do. A dukun, or shaman, says his soul was invaded by the spirit of the monkey, bat, and octopus. On his advice, Fatimah and her husband Nursah changed the boy’s name from Iqbal to Ipan and fed him tiny rice balls mixed with octopus.

“The dukun says this is why Ipan’s legs look like a monkey’s legs,” Nursah says. “Actually, I don’t believe that, but I will try anything.”Doctors say the real culprit is more down to earth: mercury poisoning. His parents are gold miners who used the heavy metal to process gold for years before Ipan was born, including while Fatimah was pregnant.Millions of people in 70 countries across Asia, Africa, and South America have been exposed to high levels of mercury as small-scale mining has proliferated over the past decade. The United Nations Environment Programme estimates that at least 10 million miners, including at least 4 million women and children, are working in small-scale or “artisanal” gold mines, which produce as much as 15 percent of the world’s gold. In Indonesia, more than 1 million small-scale miners scratch out an illegal living digging for gold in at least 850 hotspots, says Yuyun Ismawati, a 2009 winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize who has conducted extensive research on illegal mining. Ipan is one of at least 46 suspected victims of mercury poisoning in impoverished southwestern Lombok, a tourist island next to Bali. Doctors have found another 131 suspected victims in three other mining districts.Some miners heat mercury in their kitchens, where the vapors can reach concentrations that are quadruple the amounts considered safe under World Health Organization standards.

High doses of mercury, which is a neurological poison, are a well-documented cause of birth defects, including crippling deformities and nervous system disorders. The most notorious episode of mercury poisoning occurred in Japan in the 1950s when a factory dumped the heavy metal into Minamata Bay. More than 2,000 people were poisoned by the bay’s seafood, leading to deaths as well as a generation of children suffering severe birth defects.Mercury poisoning is “a serious health problem” in Indonesia, says Stephan Bose-O’Reilly, a pediatrician and environmental health expert at the University of Munich. “Prenatally, methyl mercury can harm the fetus, resulting in Minamata disease with severe birth defects and developmental delays,” he says.

Mining With Mercury

Small-scale gold mining began to take hold in Indonesia after the 1998 fall of Suharto, its longtime military ruler, and has flourished in an ensuing era of lax governance. Nearly all artisanal miners use mercury to extract gold even though the practice is banned by the government.Indonesia, with the world’s fourth largest population spread across a vast archipelago of 17,500 islands, has among the highest incidence of illegal mercury use, says Bose-O’Reilly during a recent trip to Indonesia to examine mercury victims in the gold fields.“Indonesia is a real global hotspot,” he says. “I haven’t seen anything worse than here.”Indonesia’s small-scale miners produce $5 billion in gold a year, according to Atmadji Sumarkidjo, a special assistant to Coordinating Security Minister Luhut Pandjaitan. That is about 7 percent of the country’s total gold production. By contrast, Indonesia’s gross domestic product was about $888 billion in 2014.Miners have released hundreds of tons of mercury into the water, soil, and air, often in poor, remote areas, contaminating food and wildlife.In the Central Java city of Wonogiri, where illegal gold miners have operated for more than 15 years, residents were alarmed two years ago when the local environmental agency tested guava, cassava, papaya, and banana grown in the area and found them to be highly contaminated with mercury. Doctors working with the environmental group BaliFokus Foundation, including Bose-O’Reilly, identified the 177 cases of suspected mercury poisoning on the islands of Java, Lombok, and Sulawesi, says Ismawati, a co-founder of the group. The figure includes 57 children and 59 victims who have died since they were examined.Ismawati calls it “a public health emergency.”“Children in the mining areas have been exposed to mercury since they were in the womb and some are born with deformities,” she says. “When they grow up, they inhale contaminated air, drink contaminated water, and eat contaminated rice.”

Indonesia’s Gold Rush

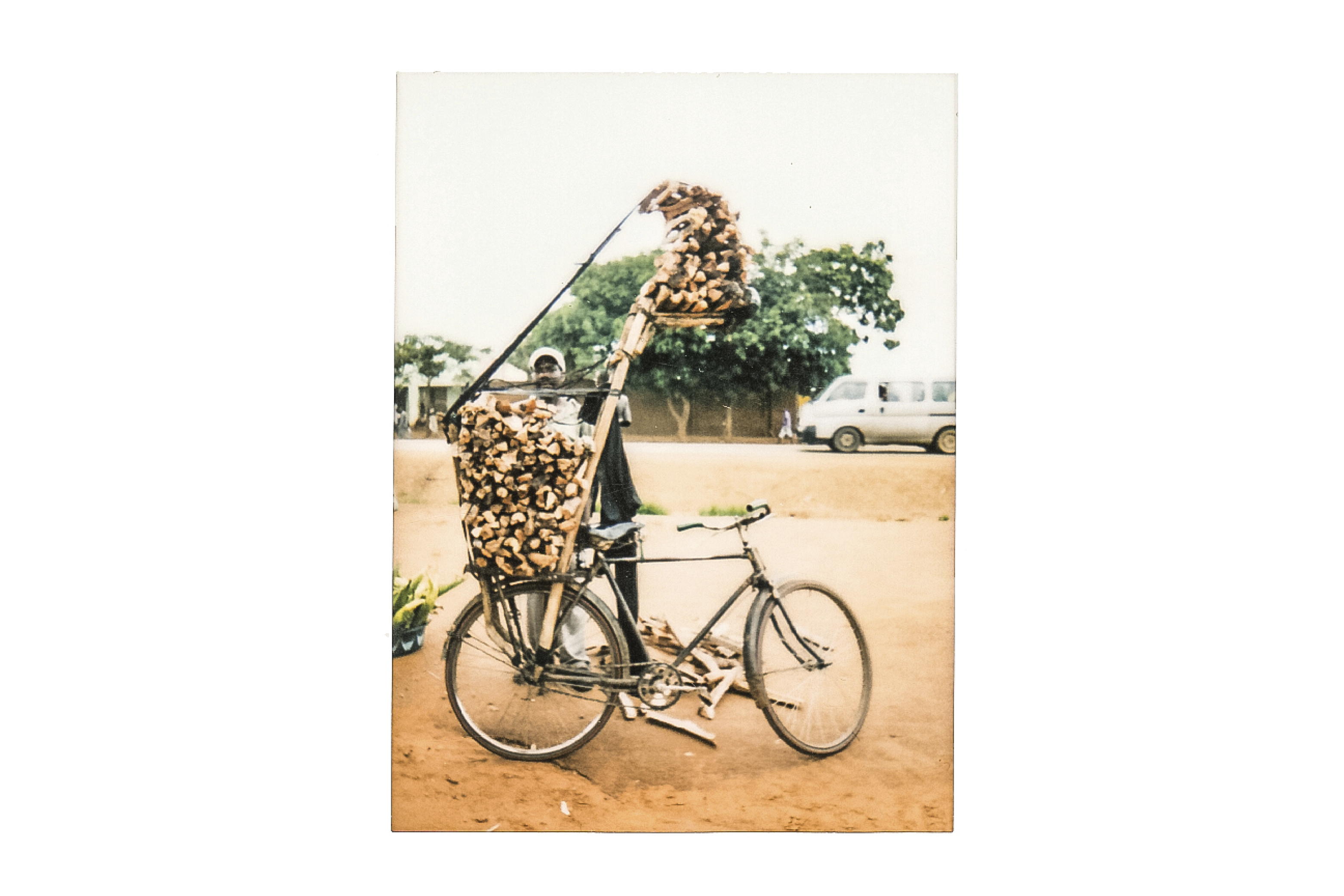

In Indonesia, miners flock to newly discovered gold fields, often in national parks or on other public land, where they operate without legally required permits. They dig deep mine shafts, tear apart mountains, dredge rivers, destroy forests, and poison the environment.

Noisy tumblers known as ball mills operate almost continually in mining communities, often next to homes, grinding the ore along with mercury and water to extract the gold. As the tumblers rattle and spin, the rock breaks down and flecks of gold bind to the mercury. Afterwards, the miners drain off the liquid and recover some excess mercury, but much of it becomes vapor and pollutes the air or flows onto the ground and into waterways.In some villages, families use mercury-laced mine waste as the foundation for their homes or to surface their yards and walkways.In the final stage of extracting the gold, the miners typically heat their mercury and gold with a blowtorch, sending poisonous mercury vapors into the air.

Child labor is common in the gold fields, with boys as young as 8 digging the ore and as young as 12 burning the mercury-gold amalgam. Mujiburrahman, 14, who lives in the West Lombok village of Luang Baluk, says he began torching mercury two years ago. “I burn the amalgam two or three times a week,” he says. “I never wear protective clothing.”The smoke, he says, simply “disappears.”Doctors have identified 24 children in mining villages in the Sekotong district in southwestern West Lombok with birth defects or ailments caused by mercury.

Among them is Lailatul Azwa, who was born in September without a left hand. Like Ipan, she suffers frequent seizures.

Six-year-old Aida was born with deformed fingers on both hands. Nyimas, who suffered from an enlarged skull and other serious deformities, died earlier this year at the age of 8. She was in a near-vegetative state all her life. Gold miners use mercury in its elemental form, which is liquid at room temperature. Inhaling the vapors produced by burning the amalgam is the most dangerous exposure, doctors say.

“Mercury vapor is very toxic to the brain, especially during development, and exposures may therefore be detrimental to pregnant women and small children,” says Harvard environmental health professor Philippe Grandjean, a leading expert in the effects of mercury exposure.

Cooking Mercury

Karto Paimin, 67, lives with his family in the placid hills above Wonogiri in a wooden, Javanese-style house with a high peaked roof and a large living area. The family has tunneled about 50 feet into the hillside below the house to find ore, which they process with mercury in their ball mill in the garden.

After many hours of labor, Paimin has produced a small lump of mercury and gold, which he takes to the kitchen at the far end of the house. The room has a dirt floor, woven bamboo walls, and a rudimentary wood stove with no chimney. Two large pots of soup simmer on the fire at mid-afternoon.

Paimin brings out a piece of pipe, which is about 18 inches long and closed at one end. He slips the mercury-gold amalgam into the sealed end of the pipe and places it in the fire. He rests the other end of the pipe in a small dish of water on the floor. His daughter, Yuni, 33, and grandson, Galang, 9, squat nearby to watch.

As the pipe heats up, the mercury melts and most of it flows into the dish. But some evaporates and the fumes escape into the room. Krishna Zaki of the group BaliFokus has lugged a portable vapor analyzer into the kitchen and tests the air. He detects about 4,000 nanograms of mercury per cubic meter, four times the World Health Organization’s safety threshold of 1,000.

When the process is complete, Paimin retrieves a hot two-gram pellet of gold, which he can sell for the equivalent of about $75.

Outside, Paimin’s wife, Dinah, 55, has been complaining of headaches and difficulty breathing. Ismawati gives her simple coordination tests, including touching her nose with her finger and moving her wrists simultaneously. She does poorly and Ismawati recommends she get tested for mercury exposure. Dinah is shocked. She and her husband had no idea mercury was harmful.

“Now I know,” Paimin laments. “But before today I didn’t know and I cooked the mercury in the kitchen.”

“Like an Iceberg”

Since Roman times, when slaves worked the cinnabar mines, mercury has been known to cause a wide range of symptoms, including headaches, tremors, drooling, difficulty walking, and eventually death. But mercury poisoning can be difficult to diagnose because it has many symptoms in common with other ailments.

The extent of mercury-related health problems in Indonesia is only now emerging as BaliFokus, volunteer doctors, and a few government officials search out victims and test for mercury in the air, food, homes, and water.

Ismawati, who is spearheading the effort, says the discovery of more than 140 mercury victims is a sign that Indonesia faces one of the world’s worst mercury disasters.

She believes that many victims have died without ever being diagnosed and that many more suffer unnoticed in remote mining communities. The cases identified so far only scratch the surface, she says. Grandjean agrees: “I’m sure that the number of poisonings is underestimated,” he says.

Erick Gunawan, a public health service doctor in Sekotong, has held two screenings in mining communities with BaliFokus’s help and found dozens of potential mercury victims. He believes there are many more who have been poisoned and hopes to hold more screenings.

“It’s like an iceberg,” he says. “You only see what’s on top but you can’t see what’s below.”

Claims of Extortion

The slow-growing environmental disaster has begun to attract attention from top officials in the administration of President Joko Widodo.

Pandjaitan, the coordinating security minister, recently cited illegal mining as one of the security challenges facing the country. Sumarkidjo, his aide, says the minister was referring in part to the illegal miners who destroy the environment and spread mercury in their communities.

He says the minister was particularly concerned by the rapid destruction and widespread use of mercury by miners on remote Buru Island, the site of a former prison in the Maluku Islands where a gold rush has drawn many thousands of miners since 2012.

“It’s not small-scale when you look at Buru Island,” he says. “It will take years to clean up the mercury.”

Gatot Sugiharto, founder of the Indonesian People’s Mining Association, says miners are forced to give as much as half their earnings to corrupt police and soldiers who control access to mining areas and demand payment. He alleges that billions of dollars go into the pockets of officials who should be enforcing the law against using mercury.

“The miners lose about 50 percent of their product to pay the extortion,” he says. “Sometimes police take it all.”

Sumarkidjo agrees that the miners’ illegal status makes them vulnerable to extortion and acknowledged that the police and military take a significant share.

“Our office does not have proof of how much they take,” the minister’s aide says. “But you can’t do these illegal things without the understanding of the authorities—the police and the local military. Everyone takes the opportunity to take something.”

Sugiharto, a former miner, advocates legalizing the small-scale miners and argues it is the only way to end mercury use.

Operating outside the law means the miners pay no taxes, depriving the government of much-needed revenue. If they were legal, he says, the government could teach them to use non-mercury methods, regulate their activities, and collect taxes to pay for health care, mercury cleanup, and land rehabilitation.

“Being illegal, all activity is uncontrolled,” he says. “They use mercury inside their houses, hiding from the public or from the officers. It’s very, very dangerous because sometimes they burn the mercury in the kitchen or in their rooms.”

Global Action

The extent of mercury contamination around the globe has prompted international action.

In 2013, 128 nations signed the Minamata Convention, named after the Japanese disaster, which aims to limit the trade and use of mercury worldwide.

The UN convention doesn’t ban mercury in small-scale gold mining but requires the signatories to “take steps” to reduce its use and eliminate it “where feasible.” Countries are required to draft detailed action plans for eliminating amalgam burning and educating the public on mercury’s dangers, among other steps.

Indonesia signed the pact but is not among the 25 countries, including the United States, that have ratified it so far. It will take effect once 50 nations ratify it.

Tuti Hendrawati Mintarsih, director general of hazardous waste in Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry, says her agency is developing the country’s action plan. But in tackling the mercury problem, she says the government is hampered by overlapping jurisdictions and a lack of funds to locate victims, provide care, and clean up contamination.

In the meantime, mining continues uninterrupted.

Resti Fauzia, 2, has never spoken a word. She stopped walking at 18 months, says her mother, Ocih. She can’t grasp objects or stand without help. When she sleeps, she has seizures.

Her family lives in the village of Pangkal Jaya near Pongkor Mountain, about 60 miles southwest of Jakarta. Illegal miners have been digging for gold there since at least 2000. More than 10,000 miners work there today.

For 15 years, Resti’s family has operated a ball mill just outside the kitchen door. Volunteer doctors working with BaliFokus examined the girl and concluded she was suffering from mercury poisoning.

On the day the medical team examined her, mercury levels outside the kitchen measured 20 times higher than the WHO safety threshold.“No one ever told us that mercury is dangerous,” Ocih says.

[This story was published in National Geographic on May 24, 2016. Reprinted with permission. Copyright © 2016 National Geographic Partners, LLC.]

Chapter 2: China’s Dirty Pollution Secret

He Guangwei is an award-winning journalist who has worked for numerous publications, including Time Weekly, New Weekly, Ta Kung Pao, and Jingzhou Daily. In China, He Guangwei has been covering the soil pollution crisis in Jiangsu and Hunan provinces and its implications for the country’s different local communities.

In both Jiangsu and Hunan, factories are causing unsafe, even deadly, levels of pollution to China’s soil, food and crops. Factory laborers in Jiangsu are dying from cancer at an alarming rate. The pollution has even seeped into the water—local officials say it looks like “soy sauce.”

Shuangqiao in Hunan Province is known as “Cadmium Village” for its factories’ emission of the toxic chemical. The municipal government closed a factory and arranged for health checks of the villagers—four died during the investigation in 2009. The people of Jiangsu and Hunan, recognizing the dire need to stop pollution, have begun to fight back. In Jiangsu, the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development is attempting to help lower the rates of environmental pollution by putting pressure on the local government. Social unrest in Hunan has led citizens petition to their government.

He Guangwei provides an account of China’s pollution crisis and its efforts to control it. But, unfortunately, the problem in China might take years, even decades, to fix.

Also in this chapter, you will find a PBS NewsHour video showing how an environmental group is trying to clean up China’s pollution. It is produced by journalist Fred de Sam Lazaro who reported on air and water pollution in Beijing.

-A.J.

China’s Boom Poisoned Soil and Crops

By He Guangwei for Yale Environment 360June 2014

When Zhang Junwei’s uncle died in February 2012, he was only fifty. In the three years that he had endured the cancer that would kill him, surgeons had removed both his rectum and his bladder. “Perhaps he was better off dead,” said Zhang, reflecting on his uncle’s ordeal. “It was a release.” Two years after his uncle’s death, Zhang still refuses to name him, afraid that even now, talking about how his uncle lived—and died—could bring trouble down on the family.

Zhang’s uncle lived in Fenshui, in Central China’s Jiangsu Province, a village of some 7,000 people that straddles a network of waterways on the western shore of Lake Tai, China’s third largest freshwater lake. Lake Tai boasts 800 square miles of fresh water, shared between Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, and has been celebrated throughout Chinese history for its abundant fish and beautiful limestone landscape.

But as China’s industrial boom gathered speed through the 1990s and the early years of the 21st century, a new, metalled road connected the once sleepy village of Fenshui to the major highway networks being built across China. Factories began to cluster along the lakeshore and the village’s traditional single-story whitewashed houses, with their signature black-tiled roofs, were steadily replaced with two and even three-story houses, as factory wages brought a surge of prosperity to Fenshui. Zhang’s uncle, like many of his neighbors, had found work in one of those factories.

His illness hit the small family hard. His only son was serving in the army when his father fell ill, and the soldier’s wage was too small to cover the medical bills. Zhang’s aunt took a factory job herself to support her sick husband, making the difficult choice to leave him unattended during her working day. The cancer was to consume the family’s savings entirely, all spent in a fruitless effort to save his life. The patient struggled through his final days at home, getting up to see to his own needs until the day he finally collapsed while fetching a drink of water. He died later that day.

Zhang Junwei (whose name has been changed to protect his identity), believes that the cancer that ended his uncle’s life was caused by soil pollution, a subject so sensitive in China that Zhang himself is still afraid to discuss it openly. Zhang has just turned 40 and, like his uncle, has lived all his life in Jiangsu, near the lake. His village of Zhoutie is just five miles from Fenshui and less than 40 miles from the county town of Yixing, in the heart of the Yangtze Delta, today China’s biggest regional economy. For more than 1,000 years, Yixing and its surrounding countryside was an important source of grain for China, celebrated in poetry as far back as 960 A.D. for its benign climate and fertile soil, and famous for the manufacture of a dense, brown pottery that is still highly prized in China as the ideal material for teapots.

But today Yixing and the land around it sit in China’s new industrial landscape. Since the 1990s, nearly 3,000 factories have been built on the once-beautiful shores of the lake. The chemical boom made Yixing one of China’s richest county-level towns, with a GDP that reached $17.06 billion in 2012.

It is also still an agricultural area: the road from Fenshui to Zhoutie runs between flat, regular fields of vegetables, these days more profitable crops than grain for farmers who live close to urban markets. But many local farmers have given up eating the crops they grow. They know that their vegetables are planted in soil polluted with cadmium, lead, and mercury, heavy metals that are dangerous to human health. Zhang confessed that he rarely eats local produce either. “There’s too much soil pollution,” he said.

Soil pollution has received relatively little public attention in China. Despite the fact that it poses as big a threat to health as the more widely covered air and water pollution, data on soil pollution has been so closely guarded that it has been officially categorized as a “state secret.”

Until recently, the Chinese government also resisted media efforts to draw attention to local epidemics of cancer in China’s newly industrial areas. It was not until February 2013 that the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) finally admitted that “cancer villages” existed in China, and released a list that included the area around Lake Tai and the villages of Fenshui and Zhoutie. Some civil society experts have estimated that there are 450 cancer villages in China, and they believe the phenomenon is spreading.

The story of the cancer hotspot of Yixing is characteristic: In the rush to develop that engulfed China from the 1990s, local officials were eager to invite factories and chemical plants into the area, and their already weak environmental controls were often disregarded entirely. “Government officials just care about GDP,” Zhang complained. “They were happy to welcome any polluting firm.” So, for a time, were the villagers who found jobs in the new factories.

The first real signs of the troubles to come were in Lake Tai itself, and were the subject of a long campaign by another resident of Yixing township, the fisherman turned environmentalist, Wu Lihong. In the early 1990s, Wu grew worried about the deterioration of Lake Tai’s once famously pure waters. He organized a local environmental monitoring group that he called Defenders of Tai Lake, to collect water samples from the lake and its feeder rivers.

For 16 years, Wu campaigned to draw attention to the lake’s declining health, despite harassment from local officials and police, and by appealing to senior government officials, he succeeded in forcing more than 200 factories to close. But his campaign abruptly ended on April 13, 2007, when he was arrested and then sentenced to a four-year prison term on charges of extortion and blackmail. The following month, the Ministry of Environmental Protection named Yixing a “National Model City for Environmental Protection.” Five days later, a toxic algae bloom turned the waters of Lake Tai into foul-smelling green sludge.

That episode, in the high summer of 2007, attracted international attention and was a major embarrassment for the national as well as the provincial government. According to the Lake Tai Basin Authority, more than 30 million people draw their drinking water from the basin’s 53 water sources. A Zhoutie local official admitted to the government newspaper People’s Daily that the algae bloom had caused a “water supply crisis,” and said the lake’s water “looked like soy sauce.” The authorities finally acted.

At the end of 2006, Yixing had been home to 1,188 firms producing chemicals. By October 2013, after six years of “rectification,” 583 had been closed down, merged or reopened as other types of businesses, as were 104 chemical plants in Zhoutie and 57 in neighboring Taihua township. In late 2013, Yixing started a new round of chemical industry cleanup, with plans to deal with an additional 52 chemical firms over the next two years.

It all came too late for the campaigner Wu Lihong. He has now completed his prison term and his wife and daughter have moved overseas, but Wu himself remains subject to restrictions, including a ban on talking to the media. His harsh treatment is a reminder to other villagers that environmental activism carries a high cost.

Pollution remains a highly sensitive subject in the district. Most interviewees were too frightened to give their names, worried about how local officials might react. Others complained that official secrecy about pollution meant that they could not discover what dangers Zhoutie’s toxic legacy might pose to their own health and that of their families. Zhang Junwei recalled that, when the pollution was at its worst, even people’s sweat was discolored. “Several of my relatives died from cancer very young,” he said.

Although the local government has now closed the worst of the factories, the pollutants those factories had released in their wastewater or sludge ended up in the soil, and the toxic waste from those polluting years continues to threaten the health of the people of the area and beyond.

Zhang Junwei and villagers like him are well aware that cancer rates in their district have risen, and they suspect that pollution was the cause. They say the number of cancer victims started to increase 10 years ago, when local farmers began to fall ill and die. Their suspicions were well founded: When crops are grown in soil contaminated with cadmium or other heavy metals, the grain absorbs the toxins. But even today, despite this awareness of what pollution can do, local farmers have little choice but to continue to plant. These are families that reaped no direct benefit from industrialization and still have few alternative sources of income. The poorest still eat locally produced food, knowing it is contaminated.

Establishing a clear connection, however, between pollution and cancer is scientifically challenging. At Hohai University, in Jiangsu Province, Chen Ajiang, a sociologist who heads the university’s Institute of the Environment and Sociology, admitted that the link between pollution and cancer is extremely complex, and it is difficult to pin down cause and effect.

In 2007, Professor Chen won a government grant to study the interaction of human and water environments in the basins of Lake Tai and the Huai River. For five years, he and his four researchers carried out field studies in the provinces of Henan, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Jiangxi and Guangdong, looking for evidence of the health impacts of water pollution. Professor Chen believed that pollution-related illness was damaging economic development, keeping villagers in poverty, or driving them away from their native villages altogether. Although he admits that the medical world has not yet identified an undisputed link between pollution and cancer in the villages he studied, his team established beyond doubt that cancer villages exist and that the lives of those who live in them are severely impacted.

The pollution that chemical factories released in gas and sludge, and in the wastewater they discharged into Lake Tai and other local waterways, has now accumulated in the surrounding soil, but the government has been reluctant to acknowledge the scale of the problem. In April 2013, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development awarded Zhoutie a “Habitat Environment Prize,” an award, like the accolade given to Xining, that seems out of tune with the real state of Zhoutie’s environment.

In the same month, the Jiangsu Geological Survey published part of a report that showed that heavy metal pollution in the Wuxi, Suzhou, and Changzhou areas has increased continuously since 2004, with once-isolated spots of pollution from cadmium and mercury now expanding and merging to form larger, continuous areas. The report revealed that between 2005 and 2011 increasing levels of cadmium were found at 37.5 percent of the sites sampled, with average increases of 0.03 milligrams (mg) of cadmium per kilogram (kg) of soil. At its highest, the annual average increase was 0.2 mg.

Continuous monitoring revealed an escalating pattern of pollution. In one unspecified area, researchers reported, cadmium levels higher than 0.4 mg per kilogram of soil were found only in relatively isolated patches in the land surrounding industrial development. But by 2012, large stretches of nearby farmland were polluted to the same levels, and rice and wheat produced in the area were contaminated.

It also described one case—later identified as the township of Dingshu, 18 miles to the southwest of Zhoutie—where, due to a cluster of township enterprises that were dumping their waste, cadmium levels in the river silt had reached 1500 mg per kg, and that rice produced on nearby land was contaminated with cadmium to levels of more than 0.5 mg per kg. China’s food safety standards rule that rice can contain no more than 0.2 mg/kg of cadmium, and the international limit is 0.4 mg/kg. Rice from Dingshu has long been in breach of those limits.

Dingshu is the center of Yixing’s ceramics industry, home to many glazed tile factories, teapot factories, and clay workshops. Yixing’s stoneware is an important source of revenue, but the factories have also badly damaged the local environment and contribute to the area’s soil pollution. Yixing launched a crackdown on ceramic factories in early 2011, but by June 2013 only 300 had been fully shut down.

The area’s problems illustrate the high price China is paying for 30 years of rapid economic development and the risks China’s increasingly serious soil pollution poses to its food. Official estimates say that China produces 12 million tons of heavy-metal-contaminated grain a year, with an economic cost of more than $3.2 billion.

China’s official approach to soil pollution has been characterized by secrecy and obfuscation. Even now, a picture of the scale and severity of the problem must be pieced together from disparate reports.

In 2010, for instance, a report on soil protection policy from the international expert body, the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), warned that overall trends in China’s soil pollution gave no cause for optimism. Quoting China’s official 1997 Report on the State of the Environment in China, it characterized the pollution of China’s arable land as “rather severe,” with pollution affecting an estimated 10 million hectares of land. By the year 2000, according to that year’s report on the state of the environment, 36,000 of the 300,000 hectares of basic farmland monitored for harmful heavy metals were found to be more than 12 percent above the standard.

CCICED’s researchers were no more optimistic about China’s system of supervision and management of soil, finding that investment in soil pollution prevention and control was too low. They stressed that soil pollution reduces the quality of crops and recommended legislation to protect the soil and to control pollution, as well as improvement in China’s environmental soil standards.

There are now signs that gravity of the soil pollution problem is belatedly forcing the Chinese government to begin to deal with a problem that has accumulated over many decades, and to reconsider its policy of pursuing economic growth at the expense of the environment. In July 2007, the Ministry of Land and the National Bureau of Statistics launched a nationwide soil survey. It was completed in 2009, but partial results were not published until December 2013. In April 2014, the government released partial results of a second soil pollution survey, conducted from April 2005 to December 2013, and covering 243 square miles of farmland. The survey reported that about 16.1 percent of China’s soil and about 19.4 percent of farmland were contaminated.

China has 135 million hectares (334 million acres) of arable land in total, but the amount of available high quality arable land has been dropping due to advancing urbanization and pollution. According to the recently released data, the government classifies more than 3 million hectares of arable land as moderately polluted. How much of that is contaminated with heavy metals is still not clear, though in 2011, Wang Bentai, then chief engineer of the State Environmental Protection Agency (now the Ministry of Environmental Protection) put lead, zinc and other heavy metal pollution at 10 percent of China’s arable land.

By official estimates, pollution cuts China’s harvests by 10 billion kg every year. In addition, official estimates say China produces 12 million tons of heavy-metal-contaminated grain a year, resulting in annual direct economic losses of over $3.2 billion.

Rising public concern about the impacts of pollution have begun to force a change in government attitudes, but changes at the top can take some time to percolate down to lower levels of government. In November 2013, delegates to the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Chinese Communist Party Central Committee—an important party meeting—adopted a key strategy document that set out the government’s priorities for the immediate future.

The document, prosaically entitled “Decision on Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reforms,” promised that environmental protection would be given more importance in the performance evaluation of local and national officials, and that local officials would be considered directly responsible for pollution. Economic growth would no longer guarantee promotion for local officials. The government also promises to put in place the legislation and powers to allow polluters to be heavily punished, a promise that began to take shape in the new environmental protection law, approved in April 2014, which removed the caps that had kept fines for polluters low.

However, Zhuang Guotai, the head of the MEP’s Department of Nature and Ecology Conservation, has said that cleaning up soil pollution is a difficult and lengthy process that will require huge investment. In some cases, he explained, the pollution the ministry had identified in soil samples could be traced back decades: pollution from the pesticide benzene hexachloride, for instance, a substance banned in the 1980s, was still in evidence.

Mr. Zhuang promised that an action plan to deal with soil pollution will pull together both central and local government and businesses, using market mechanisms to promote soil restoration, with rewards systems in place to encourage public participation. A new law on soil pollution is also promised. But soil remediation is expensive and complex, and there are no easy answers to a pollution nightmare that has brought early death to the afflicted villages, reduced harvests, and rendered much of China’s homegrown food toxic.

[This article was published on Yale Environment 360 and also published on China Dialogue on June 30, 2014. A Chinese translation is available on the China Dialogue website.]

Soil Pollution Cleanup: A Daunting Challenge

By He Guangwei for Yale Environment 360July 2014

Luo Jinzhi is 52 and lives in the village of Shuangqiao, in China’s Hunan Province. For the last several years, Luo has been a petitioner, one of millions of Chinese people who find themselves appealing directly to higher authorities in the hope of resolving a problem. Some petition to rectify a legal injustice or to expose local corruption. Luo is petitioning on behalf of her fellow villagers for a remedy for the catastrophic pollution that has afflicted her home village.

Petitioning is a demanding and difficult process in which success is not guaranteed: It involves a long and expensive journey to the nation’s capital, where petitioners are frequently sent on fruitless journeys from one unresponsive official to another. Luo Jinzhi made the thousand-mile journey, most recently this April, to plead for action with the Bureau for Letters and Calls, the first stop for petitioners in the capital, and the Ministry for Environmental Protection, only to be told to go home and wait for the local government to take care of her complaints. She has yet to hear from any of them.

For Luo and her neighbors, the first sign of a serious problem in Shuangqiao was on June 28, 2009, when Luo Bolin, a worker at the Xianghe Chemical Factory, died of cadmium poisoning. When he died, his left leg was marked by large purple contusions; he was only 44. The list of cadmium-related deaths in Shuangqiao has since grown longer, and evidence is mounting of a national pollution crisis that has contaminated China’s soil and food crops and threatens to overwhelm efforts to put it right.

The Xianghe Chemical Factory, where Luo had worked, opened in 2004, on a site just 50 meters from the Liuyang River. The Liuyang flows directly into the Xiang River and is celebrated in Chinese Communist mythology as the symbol of an historic milestone in the party’s long struggle for power. It was here, in September 1927, that Mao Zedong led the first armed Communist revolt, the brief Autumn Harvest Uprising, and set up the short-lived Hunan Soviet, an episode still commemorated in songs in praise of the river.

The factory employed 50 Shuangqiao villagers and produced an annual total of 3,000 tons of powdered and pellet zinc sulphate, an animal fodder additive. In 2006, apparently without government approval, it began to produce indium, a rare metal more valuable than gold, but the processing of which produces cadmium as a by-product. Starting in April 2008, the villagers of Shuangqiao began to notice small, but troubling changes: The local well water began to taste oddly of rust, Luo recalls, and saucepans used to boil water changed color.

On June 27, 2009, the day before Luo Bolin’s death, the government of Liuyang municipality suddenly closed the factory and arranged health checks for more than 3,000 villagers who lived within 1.2 kilometers of the plant. Five hundred were found to have high levels of cadmium in their bodies, and another four were to die during the government investigation. Shuangqiao became known nationwide as a “cadmium village.”

Luo Jinzhi has collected what she believes to be a still incomplete list of the names of the dead in Shuangqiao and the neighboring villages of Dongkou and Puhua, starting with Luo Bolin. In all, she says, she has identified 26 deaths from cadmium-related illnesses between 2009 and 2013.

Although the government paid compensation of between $1,600 and $9,000 to the victims’ families, it has never admitted a link with cadmium or other metals that have affected the villagers. In December 2008, for example, Luo Jinzhi’s five-year-old nephew began to have breathing difficulties and became listless. He was found to be suffering from lead poisoning, and 14 more cases in children had been identified by March 2009.

When the deaths began, the villagers started to protest. On July 29, 2009, hundreds of them went to the township government to complain that the factory’s cadmium pollution still threatened their lives. The next day, thousands surrounded the government building, and Chen Run’er, the party secretary from the provincial capital, Changsha, had to be called in to address them. He promised the villagers that their complaints would be investigated, but on August 5, the Liuyang authorities ordered in hundreds of police with dogs. The confrontation finally ended when the head of the plant, Luo Xiangping, was arrested, the factory was permanently shut down, and the director and a deputy director of the Liuyang Environmental Protection Bureau were fired.

Although the factory has now been shut for good, the pollution is still affecting the village. The nearly 10-acre site that the shuttered business occupied is surrounded by a six-foot wall. Behind it lies a large pile of toxic sludge. When it rains, contaminated water seeps from the sludge into the Liuyang River, just 50 meters away. Around the plant, 659 acres of land have been polluted with cadmium, and any crops grown there are contaminated. The villagers believe that moving elsewhere offers their only guarantee of safety, and they have asked Luo Jinzhi to negotiate their relocation with the township government.

Liu Bo—who is coordinator of the liaison office of the European Union-Asia Environmental Support Chengde Project, a EU-funded group focusing on urban river pollution—investigated the factory site in January 2014. He, too, concluded that “the pollution is continuing to do harm,” damaging the local land and soil and threatening the Liuyang River basin. The basin includes Changsha, as well as the Xiang River, the source of drinking water for some 20 million people.

Hunan Province is an important center for heavy metal production. In 2011, the province’s 1,003 non-ferrous metal companies produced 2.66 million tons of ten different metals—the third highest production in China and worth $60 billion. Several years ago, the government said it hoped to turn Hunan’s Xiang River into the “Rhine of the East”: beautiful, clean, and prosperous.

But in a report to an NGO conference in January 2014, Chen Chao, an official with the Hunan Non-Ferrous Metals Management Bureau, admitted that the Xiang basin also had nearly 1,000 sludge sites or tailings stores, which contained 440 million tons of solid waste that is contaminated with lead, mercury, and cadmium. Chen Chao’s report revealed that Hunan accounts for 32.1 percent of China’s emissions of cadmium, 20.6 percent of arsenic emissions, 58.7 percent of mercury emissions, and 24.6 percent of the lead, in its wastewater, tailings, and waste gases.

The scale of this ecological disaster is daunting, and the potential scale and cost of any remediation or cleanup effort is mind-boggling. According to a geochemical survey conducted by the Ministry of Land and Resources between 2002 and 2008, 794 square miles in the area is polluted by heavy metals, an area that stretches from Zhuzhou, on the Xiang River, to Chengjingji. The survey report revealed that the area’s rice and vegetables—as well as reeds and mussels in its waterways—all contained elevated levels, mostly of cadmium.

Liu Shu—who is chair of the Shuguang Environmental Protection Organization, an NGO founded in 2013 in Changsha that works on soil pollution—has investigated soil pollution in Zhuzhou, Changsha, and Xiangtan. Her group found cadmium levels 49.5 times the limit in soil samples taken from the vicinity of a smelting plant in the municipality of Changning. At another site, an industrial park by the Xiang River in Henghan County, they found levels 331 times the limit.Liu is concerned, too, about the deep-rooted social conflict between local people and government that soil pollution has caused—conflict that she predicts will worsen if not resolved. In the case of the Xianghe factory, Liu and her team noted, the villagers continue to hold out for compensation and relocation.