Letters from Editors

Spring 2018/The Women’s Issue

J. Sybylla Smith & Glenn Ruga

From the Guest Editor:

My first thought when asked to be Guest Editor of the Women’s Issue was to create a diverse and inclusive voice by harnessing a collective of women photojournalists from as wide a geographic expanse as possible. Working with an amazing jury of women photojournalists, educators, and editors for our Call for Entries, we selected five of the photo essays featured in this issue. As always, in a jurying process, individual choice is blended and a consensus is reached. I thoroughly appreciate the thoughtful consideration of my colleagues and the opportunity to work together.

My next challenge was to arrive at two overriding themes for the issue. Tragically, sexual violence was a repeated narrative with exhibits examining violence against women in war zones, in prostitution and at home. I was awed by the courageous resilience of these women and appreciate all who work to expose and ameliorate this abuse of power. I was moved to contact and include an image by Canadian photojournalist, Anica James, whose self-portrait is on page 24. She is in recovery from a premeditated sexual assault by a male peer while on assignment in Nepal. She received zero support when she reported the incident to the Associated Press, where her assailant freelanced. Her courageous and healing photo essay, After/Shock, can be viewed on SDN.

Another theme with stories from several continents was the innovation and entrepreneurship of women at work. Despite dire working conditions and competing roles as the primary parent or caregiver, women persist and provide for their families while impacting every national economy, worldwide.

I was intent on creating an international perspective when choosing books to review and sourcing writers for the reviews and feature articles. This led me to collaborate with a diverse group of women whose powerful voices are eager to offer interpretation and analysis. My research and writing on the history and current status of women photojournalists were a deep dive into our rich and overlooked history. Interviewing contemporary curators, academics and photographers was enriching and empowering. Expect to hear more from me on this topic.

Thank you for the privilege to amplify these stories captured with breathtaking intimacy, eloquence and compassion. I hope you feel their urgency and conviction to ignite positive change by revealing issues that are both hidden and those which persist in plain sight. Our shared witness yields a greater truth.

J. Sybylla Smith

____________________________

From the Executive Editor:

The idea to publish an all-women issue of ZEKE first surfaced last year when the #MeToo Movement was getting underway in earnest. We were exploring themes for the fall 2017 issue when members of the SDN Advisory Committee suggested doing a women’s issue. Everyone immediately agreed it was the right idea at the right time. We wanted to take a bold stand and acknowledge women for their contributions to the field of documentary and we agreed to devote an entire issue of ZEKE to women photographers and writers. Here it is!

I cannot say enough what an extraordinary privilege it has been to work with J. Sybylla Smith and all the photographers, writers, jurors, and volunteer staff to create this Women’s Issue of ZEKE.

One of the ground rules was that while all the photographers must be women, the themes explored could be anything. But the fact is that most of the work that came in, and two of the three themes in this issue, are women-centric. The take-away for me is that not only is there extraordinary work being done by women (it doesn’t take me to tell you that), but there is extraordinary and important work by women about women. We are thrilled to be able to present both in this issue.

I want to thank all of the women who have lent their insight, skills, creativity, and dedication to bring this issue to fruition. One person in particular, who only has a tiny credit in the volunteer staff list but deserves a bold-faced headline, is Barbara Ayotte—both my life-partner and partner with SDN and ZEKE magazine. You can rest assured that she has read every article and every word in every issue of ZEKE at least three times to make sure we are on message and typo-free. And I also want to make a shout-out to our Advisory Committee and Campaign for ZEKE supporters who make this and every issue of ZEKE possible.

Glenn Ruga

___________________________________

Cover Image

The Women’s Issue cover image is by Dutch photojournalist Marinka Masséus from her SDN exhibit, My Stealthy Freedom-Iran, addressing women’s responses to forced wearing of hijab. With the windows of her Tehran apartment covered with tinfoil to ensure that the flash would not be visible from outside, the women threw their brightly colored headscarves in the air. As it floated back to them, Masséus captured their acts of defiance.

____________________________________________________________________

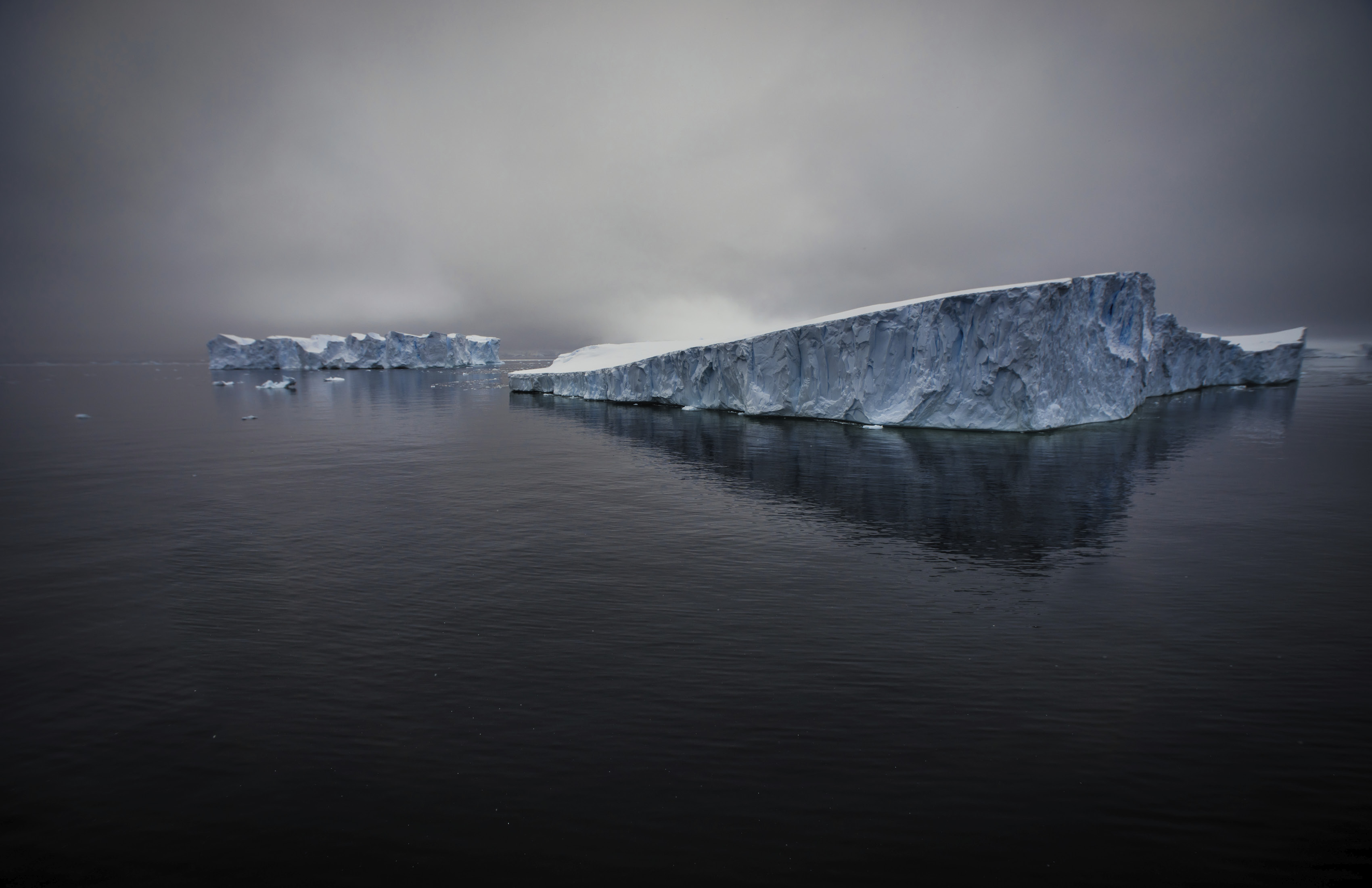

Vital Signs: Climate Change in Antarctic Waters

Photo Gallery

Photographs by Amy Martin

As a documentary photographer, Arizona-based Amy Martin uses her camera’s lens to increase awareness, understanding and compassion across physical and social barriers. Before concentrating on photography, Amy spent years working in international development and relief, including more than two years in the Dominican Republic working on environmental health and women’s health and empowerment. In Guatemala, she worked with indigenous midwives, and in Haiti on medical relief following the devastating 2010 earthquake. She has explored the issues of statelessness of Latino farm workers on the Arizona/Mexico border and the long-term effects of uranium mining on indigenous people and lands.

Martin currently works as a photographer for the Mariposa Foundation that helps to educate and empower adolescent girls living in extreme poverty in the Dominican Republic and also teaches “Identity Through Photography” workshops to children from marginalized communities. Martin is the winner of ZEKE’s recent Call for Entries, Through a Woman’s Lens. In her winning series shown here, “Vital Signs: Climate Change in Antarctic Waters,” she poetically captures the haunting beauty of the ice in every stage of decomposition as a warning and reminder of the ominous shifting in the vital signs of the planet due to human-driven climate change. “… Photography can impassion a wide audience of people by sharing the hidden story behind issues that I advocate — be it health, the environment, gender equality, or social justice. Through the dark and contemplative mood of these images, I hope to allow an exploration of the emotions surrounding these changes, acknowledge their imminent effects on humanity and, thus, provide motivation for action,” concludes Martin.

—Anne Sahler

Fire, Storm & Ice

The Impacts of Climate Change on Nature and Society

By Anne Sahler

Severe floods and wildfires in California, hurricanes in Florida and Houston, winter storms, tornadoes, heavy downpours, extreme heat and cold, and tropical cyclones have left many people dead and homeless. Extreme weather and climate events in the United States and around the globe have significantly increased in recent decades, affecting our planet’s ecosystems and the health of societies around the world

A Human-made Threat

In March 2018, weather data revealed that the Arctic had experienced its warmest winter ever in February with a rise in temperatures more than 45 degrees above normal. Since 1980, these high winter temperatures have become more frequent, more intense, and longer-lasting. What is the reason behind the alarming record-breaking temperatures in the Arctic Sea? The disappearance of sea ice. Arctic sea ice is declining at a rate of 13.2 percent per decade, relative to the 1981–2010 average. 2017 was at least the third warmest year recorded of the earth’s land and oceans since record keeping began in 1880 as well as the warmest year on record for the global oceans according to research conducted by NASA and the World Meteorological Organization.

Thanks to modern technology like earth-orbiting satellites and other technological advances, most climate scientists agree with a probability of greater than 95 percent that the increased levels of greenhouse gases since the mid-20th century due to human activity are the main cause of the current warming trend. Given the fact that greenhouse gas emission reduction plays a significant role in the threat of climate change, 195 countries have signed the Paris Climate Agreement within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Adopted in December 2015 and in force since November 2016, the agreement aims to limit the rise in global temperatures to below 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 34.7 degrees Fahrenheit. While former US President Barack Obama committed to lowering emissions by 26–28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025 and transferred $US 1 billion to the United Nations Green Climate Fund, current US President Donald Trump has pulled the US out of the Paris Climate Agreement for economic reasons, claiming the agreement was too costly for the American people, leaving other signatory countries bewildered.

The Global Effects of Climate Change

It is difficult to predict the long-lasting consequences but there are certain effects that are likely to occur: The earth will become warmer, which will result in more evaporation and precipitation; increased carbon dioxide and other man-made emissions in the atmosphere will create a stronger greenhouse effect; oceans will become warmer; and glaciers and other ice will partially melt, which will result in an increase of sea levels. But climate change has a significant impact not only on nature, but also on society. Most notably it increases volatility and threatens societal efforts to end poverty.

Already, climate change is having a measurable impact on human health, including malnutrition due to a decline in global wheat and rice yields, and the impact of extreme natural disasters forces some 26 million people into poverty each year.

Already, climate change is having a measurable impact on human health, including malnutrition due to a decline in global wheat and rice yields, and the impact of extreme natural disasters forces some 26 million people into poverty each year. The World Bank stated that by 2030, the impact of climate change could push an additional 100 million people into poverty if no urgent action is taken. Low-lying deltas in Asia as well as small island nations and coastal communities in the Arctic are considered “hotspots of societal vulnerability […] and are most certain to be impacted by climate change,” Virginia Burkett, Chief Scientist for Climate and Land Use Change at the United States Geological Survey, points out. She also stresses: “The drivers of climate change and the impacts are all associated with human-induced warming but vary from one region to another. In the US, the temperature of the coldest winter days increased by 4.78 degrees Fahrenheit in the Pacific Northwest compared to 1901–1960. Snowpack is decreasing in the western mountain region, affecting spring runoff available for crops and communities and directly affecting the ski industry. Those living in coastal Alaska are being affected by the collapse of permafrost coupled with the loss of sea ice and the accelerated rise in mean sea level.”

The arid Southwest of the US is also affected by the effects of climate change. Here, climate change has increased the intensity of heat waves and drought events as seen by the wildfires in California last summer that had an economic toll estimated at $US 18 billion. The warming climate is also considered to be the primary cause for wildfires in Alaska, causing some native Alaskan communities to leave their homes behind and move inland, away from the coast. The author of the 2007 Nobel Prize-winning report of the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s fourth assessment report summarizes the most prominent effects of climate change in the US by pointing to Louisiana, where “the sea level rise is contributing to the loss of wetlands, coastal forests and barrier islands that protect coastal communities from storm surge.” And in the Norfolk-Hampton Roads area in Virginia, as well as the US Pacific Islands, “low-lying coastal communities are experiencing chronic ‘nuisance flooding’ associated with sea level rise.”

Looking at all the social and economic effects, adaptation strategies regarding climate change are essential parts of a community’s response to climate change. Several new organizations and public websites such as the US Climate Resilience Toolkit allow communities to share climate change adaptation strategies, successes and failures.

Action Needed Now

Urgent action is required to limit the effects of near-term climate change and long-term global warming as is the need for rapid and radical measures to cut greenhouse emissions. The worst case scenario, according to Burkett, would be an “abrupt climate change. A large-scale change in the climate system that takes place in just a few decades or less, that persists and causes substantial disruptions to human systems and natural ecosystems.”

For More Information

- NASA

- Climate Science Special Report

- Climate News Network

- National Climate Assessment

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- The World Bank

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- US Climate Resilience Toolkit

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

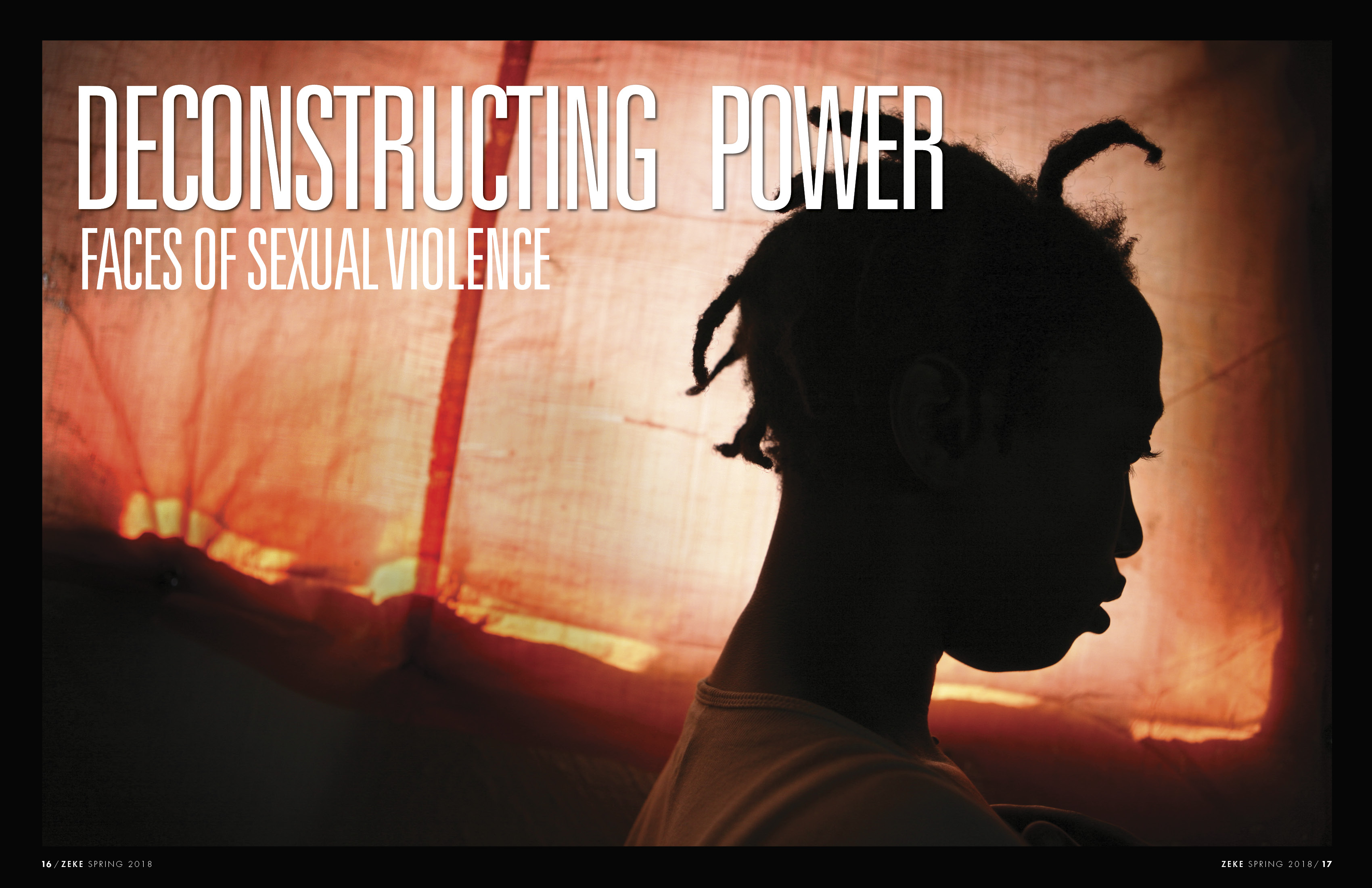

Deconstructing Power: Faces of Sexual Violence

Photo Gallery

Photographs by Diana Zeyneb Alhindawi, Jean Chung, Anica James, and Heba Khamis

“A cosmic frontier splits the planet in two halves,” wrote feminist scholar Fatema Mernissi. “The frontier indicates the line of power.” When we talk about the powerful and powerless, we may consider who is acted upon, and who escapes accountability.

Numerous studies indicate that victims of domestic, sexual, and conflict-related assault are targeted primarily by gender. According to a 2013 global report by the World Health Organization, 35.6% of women have been harmed by an intimate or a stranger, or both. As many as 38% of all murdered women are killed by a partner, compared to 6% of all murdered men. These traumas more than double survivors’ rates of psychological torment and alcohol addiction. With 42% of women who have been physically and/or sexually abused by a partner experiencing injuries as a result of that abuse, gender violence is a global health crisis.

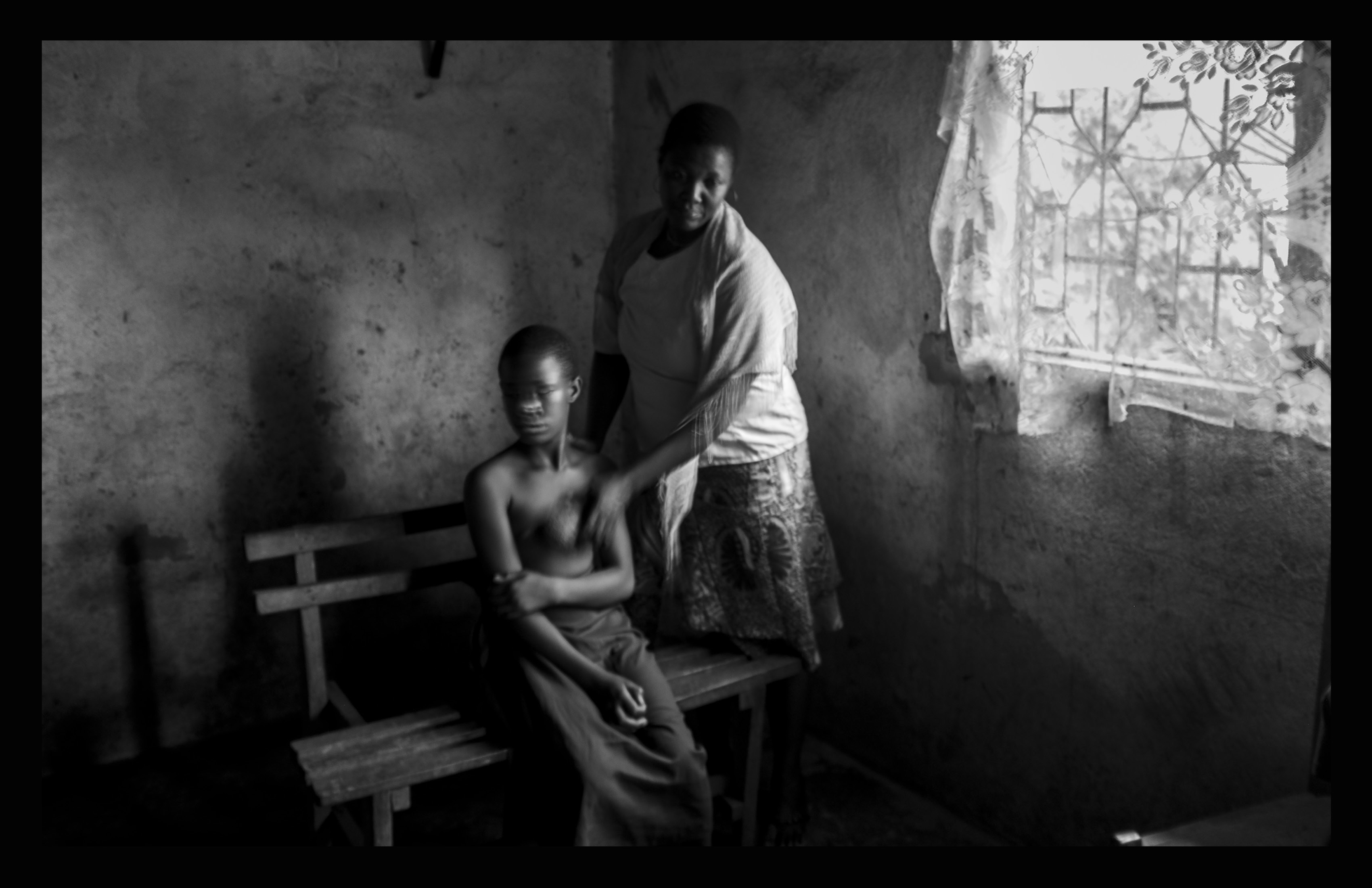

Jean Chung, a South Korean photographer, documents survivors of sexual violence and their children in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Diana Zeyneb Alhindawi, from the United States, follows the brave witnesses testifying in the Minova rape trial in the DRC. Canadian photographer Anica James shares her personal experience of harassment and assault by one of her colleagues, and Egyptian storyteller Heba Khamis renders intimate portraits related to breast ironing in Cameroon.

In these folios, women photographers are deconstructing power and seeking to interrupt descriptions of survivors as invisible, powerless, voiceless, or stripped of their inherent dignity.

—Ladan Osman

A Valley of Echoes

The Global Prevalence of Gender Violence

By Ladan Osman

Gender-based violence is widespread, the statistics staggering regardless of the victim’s age, economic status, or nationality.

In scriptures, poetry, constitutions, and leaders’ pledges to protect all members of the state, women are often listed with children, or others rendered “vulnerable” by circumstance. The woman citizen is imagined as less adult. Is it possible that vocabularies that consider women as objects make a quiet argument that the assault on our person is inevitable? Gender-based violence is widespread, the statistics staggering regardless of the victim’s age, economic status, or nationality.

In conflict-challenged regions, women and children are especially susceptible to attack by assailants who in part consider their bodies part of a territory to conquer. There remains a lack of reliable data on violence experienced by a non-partner, and violence in conflict-affected settings. “When we think of war, we think of it as something that happens to men in fields or jungles,” writes Eve Ensler, artist and founder of V-Day, a movement to end gender violence. “But after the bombing, after the snipers, that’s when the real war begins.”

A Siege on Civilians: the Aftermath of Minova

For ten days in November 2012, soldiers in the Congolese army seized the market town of Minova. In a sequence of attacks that seemed determined to raze the morale of ordinary citizens, at least seventy-six women and girls were raped. It should be noted that other reports estimate hundreds of assaults during those ten days. The findings in a 2013 report by the UN Joint Human Rights Office (UNJHRO) indicate that “rape is used as a weapon of war to intimidate local communities, and to punish civilians for their real or perceived collaboration with armed groups or the national army.” Most of these rapes were committed “during attacks aimed at gaining control of territories rich in natural resources.” There are devastating metaphorical links between women and properties, solidified by social practices around the world. The mythology of the fertile woman becomes tangled with invasions of verdant land.

Following domestic and international outcry, and a demand to apply the government’s zero tolerance policy towards these crimes, fourteen officers and twenty-five rank-and-file soldiers of the Congolese army were put on trial in Goma, the largest rape trial in the nation’s history. Seventy-five survivors gave testimony, veiled by curtains or clothing to protect their identities. The verdict was given by a local military court: while thirty-nine were accused, only two low-ranking soldiers were convicted, each for one assault. Since Minova, there have been incremental improvements in the carriage of justice. According to the UNJHRO report, there were “187 convictions by military jurisdictions for sexual violence between July 2011 and December 2013, with sentences ranging from 10 months to 20 years of imprisonment.” When President Joseph Kabila addressed parliament on October 23, 2013, he vowed to make the Democratic Republic of Congo “an inhospitable land for the perpetrators of these heinous crimes.” On December 12, 2013, President Kabila signed an accord in Nairobi, refusing amnesty for war crimes committed by rebel soldiers. The protocols launched in 2014 were revised in 2017. Although faced with local instabilities and waning international support, organizers and survivors in the DRC continue to lead the fight towards justice and healing. “People think that, after being raped, you are just a victim…life goes on after rape. Rape is not the end. It is not a fixed identity,” said Jeanna Mukuninwa, aged 28, from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“The perpetrators thought that they were untouchable, that nothing would happen to them. The tipping point that we are now talking about is the change of that culture.”Phumzile Mlambo-NgcukaExecutive Director of UN Women

Painful Protections

In 2014, Julie Ada Tchoukou published one of the most comprehensive studies on breast ironing in Cameroon, a mutilating practice “whereby a young girl’s developing breasts are pounded, pressed or massaged with an object usually heated in a wooden fire, to make them stop developing, grow more slowly or disappear completely” in order to protect her from sexual knowledge and attack. The much-cited 2006 report published by German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) (but no longer online) found that “25% of all girls and women had experienced some form of breast ironing in their lives, although the prevalence rates differ depending on location.” Lasting effects include cysts, mastitis, disfiguration, inability to breastfeed, and depression. Tragically, the very act meant to prepare a girl for sexual engagement within acceptable parameters may leave her less emotionally and physically capable of enjoying the pleasures of womanhood. Chi Yvonne Leina, founder of Gender Danger (a grassroots organization aimed at ending breast ironing), relates a particularly disturbing account of a woman named Geneva Ikome who ironed her own breasts in primary school, calling herself “a victim of breast ironing, and a perpetrator, too.”

Tchoukou notes the use of the grinding stone, inferring that guardian women in Cameroon “believe that the preferred tool used in breast flattening can reconstruct breast tissue in the same way it transforms spices.” Absurdly, in Vice’s coverage of this practice in 2015, the magazine mentions Gildas Paré (who made portraits of survivors and breast ironing implements) was a former food photographer. It’s worth stating the difficulty in tracing studies and their methodologies, and too-often ethnographic approaches to documenting this traumatic practice. In recent years, western attention on breast ironing increased when the British Parliament attempted to address the issue within its population. Another factor affecting statistics and narrative framing of breast ironing is a girl’s will to protect her female guardian. The assumed right to protect girls from violence with violence is one response from the defensive positioning many women take in order to stay alive. This vigilance may be a corrupted survival instinct, formed from a long and brutal education.

Revising Culture

Social expectations for girls and women, which emphasize passivity, silence, and innocence, place the burden of assault on the victim. Further, shallow definitions of honor and devoted motherhood are troubled by the effects of this abuse, which more than double survivors’ rates of psychological torment, alcohol addiction, and induced abortion as compared to women who haven’t suffered from this violence. The private spheres evade application of law, and this abuse becomes secret or codified as “culture.”

“The perpetrators thought that they were untouchable, that nothing would happen to them,” Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director of UN Women said in her address in March 2018 to The Commission on the Status of Women. “The tipping point that we are now talking about is the change of that culture.”

Award Winners

Honorable mentions from SDN’S call for entries on “Through a Woman’s Lens”

Jurors: Barbara Ayotte, Aida Muluneh, Amy Pereira, Molly Roberts, J. Sybylla Smith, Deborah Willis, Ph.D., Amy Yenkin, Daniella Zalcman

ZEKE presents these four honorable mention winners from SDN’s Call for Entries “Through a Woman’s Lens.” The jurors selected Amy Martin as the first place winner (see Vital Signs), and the four photographers presented here.

Interview with Aida Muluneh

by Caterina Clerici

Born in Ethiopia, Aida studied film at Howard University in the US and then went on to work as a photojournalist at the Washington Post. Her work has been exhibited throughout the world and is in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art, Hood Museum, and the Museum of Biblical Art in the United States. Aida is the founder and director of the Addis Foto Fest and she continues to curate and develop cultural projects with local and international institutions through her company DESTA (Developing and Educating Society Through Art) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Caterina Clerici: How did you get into photography? Was your passion for photography related to the fact that you lived in so many different places at a young age?

Aida Muluneh: I was interested in photography from an early age. I’ve always been obsessed with images. During high school in Canada, we had a really great art teacher who took a few of us to the darkroom. When the first prints came out, it was almost like a magical moment for me.

As an Ethiopian and having lived in so many different places, people that I encountered always had misconceptions about Ethiopia. Granted, we were going through the famine in the 1980s, but that didn’t really match with the story I heard from my mother: Ethiopia was a far more complex place than the media was portraying it to be. So from that point on, I became aware of the misrepresentation you see in the media, and this triggered my life-long work. I really wanted to share with the world something a little bit different, not only about Ethiopia. I was living in the US and Canada, so I was always focusing on people of color, especially African-Americans and how they are portrayed in the media. That’s basically my journey to photography.

I’ve had great mentors, most of them African-American photographers. Coming back home was basically taking that conversation to Ethiopia. Now I’ve been there 10 years and this is what I’m pushing forward with my work, with the festival and panel discussions. As Africans and people of color, we need to be more engaged: not only producing images, but also writing stories on who we are.

CC: How are you trying to reclaim a different narrative of Africa with your work?

AM: I’m really trying to present work that has universality in it. I cannot deny my roots or my heritage or my culture, which will come into the work, but I’m trying to create bridges across our common humanity.

What I do is very personal work. It’s not something that I’m over-philosophizing about, but rather that I’ve either experienced or encountered along the way when I was working as a photojournalist. It’s about how to share the challenges in a different way, outside the blood, the beheadings and all the gore. I’m trying to make Africa digestible, meaning it’s a very complex place, it’s not so simple, and I’m only one person sharing my experiences. This is to share with the world — but also the continent and my people — that there is a different way of expressing a story, especially through photography.

If you look at the foundation of body painting for instance, you see this traditional body ornamentation in Africa but also in South America, Asia, and the Middle East. I’m taking things of the past and bringing them into the future, but also twisting them in a way that I’m having a different dialogue based on my personal experience that I want to share with all. It’s about raising questions, I’m not here to give solutions. There are many things that need more questioning, in terms of the direction we are going; not as nationalities, or based on borders and colors of our skin, but to look at collectively.

CC: One of the strongest influences of African tradition on your work seems to have been body painting. How did you get into it?

AM: Body painting has a different play depending on the series and the image. If you notice, the models look alike but there is a specific structure I look for in the face. It’s a way to remove race and gender; I’m trying to have a very specific message. The photos are also all women. Somebody asked me why I don’t pick men and that’s because I’m a woman telling the female story.

When I was at Howard University there was a fashion show and they had asked for an image to promote it. I picked two models that were going to be on the runway and I was really trying to show my African roots in my photography — you know, the challenge of duality is that you never fit anywhere — so I thought: “Let me paint the models and put these white dots!” The picture never got picked for the fashion show, but that was the beginning for me. I was shooting analogue at the time, I did three pieces and kept the images for myself. Then a few years later, I was selected for an exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art, a show titled “Ethiopian Passages.” It was the first time I exhibited that work and it became part of the permanent collection.

After that I didn’t do any body painting for a while. I was in the middle of my journalistic work and immersing myself in documentary filmmaking. Many years later Simone Njami asked me to create a body of work for the Divine Comedy exhibition. I was trying to figure out if I should go back to my black and white, or do something completely different, or go back and explore body painting after ten years. I did that and was very insecure about the work, because I thought people didn’t expect that from me, but the reaction was amazing. After that, I started researching body painting globally and started seeing patterns, and I’ve been doing it since.

CC: You left Ethiopia a long time ago; in an interview, you said you moved back “with humility” and have felt like a foreigner in your own homeland. How do you come to terms with these two sides of your identity, and how does that affect your work?

AM: I left when I was five, lived in Yemen, Cyprus, England, all these different places. The only common thread was my mother’s insistence never to forget the homeland. I think the greatest gift that she gave me was that we couldn’t speak English in the house. Going back (to Ethiopia), the big advantage that I had was I could speak the language: I had a better chance to learn and fit into society.

Ethiopia really inspired me: I would not have been producing the same work that I do now if I didn’t live back home. There are so many textures that you don’t see anywhere else, for me this became a motivation to create this work. A lot of images I produce actually have a coding, patterns or references that only Ethiopians can understand. I would have never learned this in the West. Also, the West has a way of hiding certain realities, while here everything is in your face, even difficulties, and you have to find ways to deal with it. There are many challenges, but there is also a lot of grace. I had to learn, as opposed to impose my way of thinking.

CC: How do you think your work is helping change the perception of the African female body, in Africa and elsewhere?

AM: If you look at archival photos from Ethiopia at the turn of the century by European dudes who showed up to take photos of exotic Ethiopians, there is a lot of cultural misrepresentation, because the focus was making things exotic. They would take a photo of a woman with exposed breasts, but as an Ethiopian when you look at that, the cultural references don’t make sense — we know that that’s not the way a woman would be dressed in that region. Exoticising women’s bodies was a trend: with white women in Europe it would be considered pornography, but with black bodies it was accepted, it looked like an ethnological approach. The poses of women are very specific, and to me it’s more to emulate strength and pride of women as opposed to the vanity side.

We are in an extremely conservative society here. I don’t think anyone is yet thinking about the use of women’s bodies in my work. The first conversation is the face painting, then the colors and then the composition. It penetrates in different segments — from the government’s TV program to local hotels who have stolen my work to promote tourism in Ethiopia. So if it reaches that wide of an audience, it’s fascinating. How do I make an impact on the everyday person? That’s what matters: not teaching photographers, but teaching everyone else what the role of photography is in society. You have to educate before you can even get to the tougher conversations about how you document and what stories go out.

CC: How did the idea for the Addis Foto Fest come up and what is the aim?

AM: I arrived in Addis in 2007, after the Bamako Biennale, which was eye-opening: I had spent most of my life thinking that I was alone in my quest for changing the image of the continent. Meeting all these photographers from all over Africa and the world in Bamako and having this conversation with them was really inspirational.

I had been thinking about the festival as a way to connect photographers in Africa and the diaspora, because I saw that the conversation they were having in Africa and among African-Americans in the US was a similar one: it was about misrepresentation. They had just never met in one space to have this conversation together. When we started in 2010 that was the concept: have a global interaction to shift the conversation. We wanted to create the space and give them a different idea of Africa, so they could take it back to their own communities. Unless you’re on the ground, you won’t understand the fuller image.

CC: Is there a growing space for women photographers in Africa?

AM: I’ve been seeing a rising number of female documentary photographers, especially thanks to the festival, but we need to push more for the female voice. I was on the jury of the World Press Photo and you know, 83,000 submissions and only 15% are women. This is still a very male-dominated industry, regardless of whether you’re looking at Africa or Europe or the world. To me, the challenges are based on my own personal perceptions and limitations, but I found that being a woman has more advantages and it gives you more access to whatever you’re trying to express. I’ve seen some improvement, but it’s still not enough.

Women Work

Photo Gallery

Photographs by Casey Atkins, Delphine Blast, Joan Lobis Brown, Vidhyaa Chandramohan, Susan Kessler, Valerie Leonard, Maranie Staab, and Beata Wolniewicz

According to UN Women, nowhere in the world has women’s participation in the labor force reached parity with men. While women are increasingly well-educated, labor markets still channel them disproportionately into work considered traditionally acceptable for women. Too few reach upper-level positions in management and leadership. According to the International Labor Office, women earn 77 percent of what men earn. These gaps are linked to the undervaluation of the work that women undertake and the need for women to take career breaks to attend to unpaid childcare and household family responsibilities.

Around the world, women are resilient, dedicated, and putting in a hard day’s work. Adrienne, in Joan Lobis Brown’s exhibit “Women of an UNcertain Age” worked 100 hours a week as a nurse practitioner to buy the equipment for her practice while she raised three kids. In “Women of the Congo: Farmers, Harvesters, Mothers,” photographer Maranie Staab highlights the strength and grace of Congolese female farmers. Despite their demanding activities, women who work the fields are still considered the inferior sex yet they continue to move ahead with quiet determination to positively impact their future.

In “Women’s Worth” by Casey Atkins, Nicaraguan women challenge the male-dominated economy by owning their own businesses. Women thrive through food production, an industry which allows for flexible hours and the ability to work from home. This convenience of home-based ventures gives low-income women the opportunity to provide for their families.

Photojournalist Beata Wolniewicz, in her exhibit, “Tough Life, Strong Women,” captures the labor of women in Ghana, subject to difficult and often times dangerous conditions in the production of cocoa oil. Despite challenges these women find joy and gracefully accept their responsibilities.

In “Peruvian Weavers,” Susan Kessler documents women weavers in the Andes Mountains of Peru who support themselves financially while retaining their traditional way of life.

For a dollar a day, women break coal from the mines in the State of Jharkhand, in northeast India. Valerie Leonard’s exhibit “Black Hell” depicts the toxic environment as women sacrifice their lives for economic development. Around the world, women are migrating to seek work and better lives. In “Transnational Mothers,” Vidhyaa Chandramohan captures the challenges migrant workers encounter while working in a foreign land, far from their children.

—Ezinne Ukoha

The Economic Power of Women

by Ezinne Ukoha with contributions by Wendy McDowell

With advancements in technology, female entrepreneurs are discovering new opportunities to be competitive with their male counterparts in the international arena.

Many of the world’s women hold dual roles as workers and as mothers/caregivers, but their important contributions to the global economy are downplayed and undervalued. Though women contribute to the economic viability of their families, communities, and nations, the stereotype persists that “breadwinner” men are more valuable members of the workforce. In addition to their paid work, women throughout the world engage in a remarkable range of unpaid housework and care work each day. This includes fetching water, preparing food, and caring for the young, old, sick, and disabled.

When paid and unpaid work are combined, women work more than men the world over. This disparity is particularly stark in developing countries. According to an International Labour Organization (ILO) report Women at Work: Trends 2016, other important factors that underscore the inequities at work include: a higher share of women in part-time employment, and more women than men underemployed against their wishes.

Women are also more likely than men to work in the care economy, in jobs that are too often underpaid, unregulated, and do not offer worker benefits. The ILO estimates that over 100 million workers survive through the care economy, over 90 percent of whom are women and migrants. Migrant women are the most vulnerable, often subject to long hours, low pay, and unregulated working conditions, without access to benefits or legal protections that might mitigate these harsh realities. Migrants often remain dependent on their employers for basic amenities, living arrangements, and to shield them from deportation.

Women are essential to agricultural production, especially in the developing world, but this work also tends to be informal, unpaid, and invisible. A report from Global Volunteers notes that “women comprise 43 percent of the world’s agricultural labor force—rising to 70 percent in some countries.” UN WomenWatch points out that “Rural women play a key role in supporting their households and communities in achieving food and nutrition security, generating income, and improving rural livelihoods and overall well-being.” Yet this report also notes that “globally, and with only a few exceptions, rural women fare worse than rural men and urban women and men for every Millennium Development Goal indicator for which data are available.” This is due to lower education and literacy rates among rural women, a lack of services and infrastructure, and their underrepresentation in politics and decision-making groups.

Progress Made but More Needed

There has been some progress during the last 20 years. The number of women engaged in informal work has decreased (down by 17 percent); the amount of time women spend on unpaid work has narrowed (mostly due to a reduction in time spent on housework); and the number of women engaged in entrepreneurial enterprises has increased. A 2016/2017 Women’s Entrepreneurship Report from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) estimates that “163 million women are activating new businesses while about 11 million are responsible for the operations of already established ventures,” and notes a 10% increase in overall female TEA (total entrepreneurial activity) in the past two years.

With advancements in technology, female entrepreneurs are discovering new opportunities to be competitive with their male counterparts in the international arena. However, in parts of the world crippled by underdevelopment, women still do not have the tools and technological capacity to compete. Other systemic problems stymie women business owners, including a lack of supportive civic organizations and commercial lending systems that tend to be biased against women.

Even if female entrepreneurs were to be fully supported, this would not improve the lives of most women at work given widespread “occupation segregation”—in the US, for example, four out of ten women work in lower paying occupations where at least 75% of the workers are female. According to a 2015 poll of more than 9,500 women in the G20 countries, “work-family balance” was the top work-related issue for women (equal pay and harassment came in as the second and third respectively).

Legislation Needed to End Inequality

Governments need to tackle these issues of inequity head on by developing national women’s economic development strategies that help level the playing field and empower women workers. At the least, policies must be enacted to provide protection and recourse for exploited workers, requiring employers to engage in wage transparency, provide adequate job training, and institute nondiscriminatory job reviews. The ILO concludes that work-family policies are the most important ingredient; they are “the missing link to more and quality jobs for women.” Thus, the ILO calls for the adoption of international labor standards “promoting non-discrimination, equal remuneration for work of equal value, social protection, maternity protection and support to workers with family responsibilities.”

To facilitate these changes, already established women’s trade organizations and unions need to be supported and new ones need to be formed. One example is the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) in India, a trade union which makes visible the typically invisible work of poor, self-employed women (94% of working women in India work in the “unorganized sector”). There are also effective NGO programs and partnerships that can be expanded and replicated, such as “Better Work,” a joint project of the ILO and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) to increase gender equality in the garment industry. Appointing more women to key economic positions is important, as well. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, a Nigerian economist and the first female minister of finance in the region, was responsible for initiating programs to help women and children such as the Growing Girls and Women in Nigeria Programme (GWIN) and the Youth Innovation program (YouWin).

If work opportunities and conditions improve for women, it is not only women who will benefit. Each country, and the entire global economy, will see growth. A 2016 McKinsey Global Institute study calculated there would be a whopping $12 trillion added to the global annual GDP in a “best in region” scenario “in which all countries match the rate of improvement of the fastest-improving country in their region.” In a “full potential” scenario in which women play an identical role in labor markets to that of men, the study concludes “as much as $28 trillion, or 26 percent, could be added to global annual GDP by 2025.”

Hopefully the challenges women face as workers will be recognized and wide-ranging solutions will be found. When women are championed, they contribute, create, innovate, and become forces of economic sustenance and power for their families, communities, and the world.

Through a Woman’s Lens

By J. Sybylla Smith

The historiography of women’s photojournalistic work, while still sparse, has gained ground in the past thirty years, due to the stellar and consistent work of female photographers, academics, museum curators, and editors. The fields of photojournalism and documentary photography reflect the political, social and cultural configurations of predominant ideologies.

Our understanding of what is history-making and newsworthy has been predominately defined and captured through a patriarchal lens. We need to know and understand our own history.

This article illustrates the myriad ways in which women photographers have always been in the picture despite historically inequitable access—seeking truth, bearing witness and making invaluable contributions. We look back to reclaim history and honor the creative strategies of these women. We also look at innovative storytelling by contemporary women whose practices illustrate how seeing the world through a woman’s lens concurrently informs and transforms photojournalism and our understanding of the truth.

Witness: A Historical View

Women photographers have witnessed and chronicled our world since the camera was invented in the mid-19th century. Unlike other fine art forms, women were introduced to photography in tandem with men. In 1893, the Eastman Kodak Company targeted the use of their newly invented hand-held camera to women. Their highly successful marketing campaign featured the “Kodak Girl,” an independent camera-carrying world traveler. At the same time Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864–1952) set up her Washington D.C. studio and became the first woman press photographer in the United States. She covered the White House and published an article, “What a Woman Can Do With a Camera,” in 1897.

Journalist Elizabeth Bisland made this observation in 1890: “Women with their cameras surpass all traditions and stand as the equals of men in their newly found and now more ardently practiced art…Indeed it seems as though for six thousand years women have been nurturing a talent to which she could give no expression with paint, brush or sculpture…Our greatest painters have been men, have we not a right to expect that our most famous photographers will be women?” This quote was featured on the wall of the 2015 exhibition “Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers? 1830–1919 and 1918–1945” held jointly at Musee de L’Orangerie and Musee D’Orsay in Paris.

“Our greatest painters have been men, have we not a right to expect that our most famous photographers will be women?”

— Elizabeth Bisland, 1890

The exhibition highlighted women photographers’ positive impact on the outcome of the suffrage movement while acknowledging their important coverage of World War I. The catalog states; “This was the time when they covered the struggle for women’s civil rights and the events of the Great War — a time when, through various forms of social commitment, the history of photography and the history of women joined forces…By the start of the First World War, the medium had enabled women, for the first time in their history, to control their public and political image.”

Meanwhile, groundbreaking documentary work was being made in America by pioneering photojournalist Alice Austen (1866–1952). Austen chronicled her native New York City’s response to the immigrant influx for a decade beginning in the 1890s. She photographed the quarantined migrants, the medical laboratories and the equipment used to clear immigrants for entry. Austen has 150 of her photos copyrighted with the Library of Congress, many of which were exhibited in Buffalo at the Pan American Exposition in 1901.

Hilary Roberts, the Research Curator of Photography at the Britain’s Imperial War Museums, adds immensely to our historical knowledge. In A Woman’s Eye: British Women and Photography during the First World War, she introduces us to Christina Broom (1862–1939) and Olive Edis (1876–1955), professional photographers working to support their families in 1903. Broom was given an official military appointment in 1904 and is recognized as Britain’s first female press photographer. Though denied access to the battlefield, Edis received official permission to travel and documented the end of WWI in March 1919.

Val Williams, in her book, The Other Observers: Women Photographers from 1900 to the Present, notes the significant role that women photographers have consistently had: “Many women took their cameras with them when they traveled abroad to become war workers, and the intensity of this new experience resulted in photographs which firmly established women as social documentarists.” A common strategy women utilized to gain access to the front lines was by providing auxiliary health services. Elsie Knocker (1884–1978) and Mairi Chisholm (1896–1981) established a medical post in Belgium in 1914. As amateur photographers they photographed their surroundings and those of the soldiers. Roberts describes their intimate portrayal of death and destruction as “entirely unsentimental documentation.” While working as a Red Cross nurse, Florence Farmborough (1887–1978) documented the trenches, troops and the dead soldiers on the Eastern Front in 1915 Russia.

Another strategy used to enter the predominantly male field was to assume an androgynous name. Gerda Taro (nee Pohorylle, 1910–1937) initially submitted work for consideration using the spelling of her name backwards. Taro was instrumental in changing the life course of her partner, Endre Friedmann (Robert Capa), when they met as emigres in Paris in 1934. Both assumed pseudonyms and one went on to become a revered photojournalist. Author Jane Rogoyska details the transformation in Gerda Taro, Inventing Robert Capa. Her deep commitment to covering the Spanish Civil War led her to Madrid in 1936. At 26, she became the first known woman photojournalist to be killed on assignment. It remains a matter of debate whether images credited to Capa were actually her work.

Following in Taro’s footsteps of intrepid and impassioned eyewitness coverage of conflict was the work of American photojournalist Dickey Chapelle (1919–1965). She is noted for having defied naval command to gain access to the battlefield in World War II and is credited with capturing the iconic and heralded image of the wounded at the Battle of Iwo Jima. In 1956, she was imprisoned while working in Hungary. She wrote a memoir in 1961, What’s A Woman Doing Here?. Shortly after, she dove into coverage of the Vietnam War. She was the first American female war correspondent killed reporting for the National Observer in 1965.

Women photojournalists in the late 20th century, while still a small minority, were beginning to be recognized for their contributions. The first woman to be awarded the coveted World Press Photo of the Year Award was French photographer, Françoise Demulder (1947–2008), who won the 1st Prize Singles, Spot News in 1977. She covered conflict in Vietnam, the Middle East, Cuba, Pakistan and Ethiopia. Another French photojournalist, Catherine Leroy (1944–2006), was a trained parachutist and jumped in Operation Junction City with the 173rd Airborne Brigade in Vietnam in 1967. Her resulting image became a Life magazine cover and she wrote the accompanying feature article.

Journalist Elizabeth Becker, author of America’s Vietnam War: A Narrative History, wrote a 2017 New York Times article, The Women Who Covered Vietnam, in part as tribute to “what has been glossed over in the annals of conflict.” She and other female correspondents were not dispatched by “enlightened newsrooms” in 1960, but paid their own way to Saigon, including one reporter who entered a quiz show to earn her one-way fare. Becker’s article ended with a rhetorical question. “Did it make a difference having women report war? Absolutely. Considering our small numbers—a few dozen, over the course of a decade, spread across three countries—we had an outsize impact.”

Truth: Today

Progress toward parity is incremental. Legislation addressing gender equity in the workplace has occurred in some countries, however social and cultural norms lag far behind. Women photographers’ perseverance and creativity have diligently given voice to truth through witness. Writer and historian Rebecca Solnit reflects in Hope in the Dark: “How the transformation happened is rarely remembered, in part because it’s compromising…and it recalls that power comes from the shadows and the margins, that our hope is in the dark around the edges, not the limelight of center stage.”

Photographer Daniella Zalcman, recognizing the gender disparity in photojournalism, created Women Photograph last year, a website that contains a database of women photojournalists. According to Zalcman, in an interview with the New York Times, “the issues that female photographers face are complex but include gender prejudice, hiring practices, a possible confidence gap between men and women, strains on personal lives, sexual harassment, and a general decline in the media industry.”

The photojournalism field is currently in public discourse on gender equity following the announcement of the all-male awardees for the 2018 World Press Photo’s Photo of the Year award. Out of 51 award categories, women are represented in only five of them. An examination of the constructs which perpetuate discrimination within the field of photojournalism needs further analysis. Women’s equity in this field calls for proactive measures to ensure non-discriminatory practices and protection from all forms of sexual violence. In January 2018, photographers Justin Cook and Daniel Sircar posted an open letter on PDN (Photo District News) signed by more than 410 men in the photography industry, calling for an end to sexual harassment, sexual coercion, sexual assault and abusive behavior in the industry, sending the letter to workshops, conferences, and leading organizations in photojournalism. Several professions are coming to a reckoning with their inherently discriminatory constructs. As Solnit reminds us, “We write history with our feet and with our presence and our collective voice and vision.”

Women photojournalists have been rewriting the narrative of documentary photography in a remarkable manner despite the existence of sexism. Canadian photojournalist, Rita Leistner, believes women have turned a disadvantage to an advantage, “I’ve had the door shut in my face for being female.” She states that while exclusion continues it is in less overt forms. Lack of access and funding led Leistner to illegally walk into Iraq from Turkey in 2003. In Baghdad, without military clearance, she began a visual narrative of the inpatients in Al Rashad Psychiatric Hospital. After fighting surrounded the hospital, her former disadvantage became an advantage as the staff and families gave her access and protection. Leistner was awarded the 2018 World Press Photo Digital Storytelling Award in Innovative Storytelling for From Janet With Love.

Women photographers have explored the truth and bared witness with profound effect. Photojournalist Stephanie Sinclair’s investigation of immolation uncovered the practice of forced marriage by children, some as young as five. Her decades-long project led to an international non-profit organization to protect girls’ rights and prevent child marriage. Her transmedia campaign, Too Young to Wed, has led to widespread awareness, advocacy and action.

Documentary photographer, filmmaker and journalist Sara Terry is the Founder and Artistic Director of the Aftermath Project, a grant-making, educational non-profit founded on the premise that “War is Only Half the Story.” Commenting on the value system used to define news, she notes, “The feminine point of view, which men can have, has not been prioritized. It has been marginalized and judged to not be considered a decisive factor for a feature story.” Aftermath just celebrated its 10th year, in spite of not receiving mainstream financial backing or news coverage.

A wave of women photojournalists tell their stories as insiders and challenge existing discriminatory power structures in their respective countries. Newsha Tavakolian, the youngest photographer to cover the 1999 Iranian student uprisings when she was 18 years old, is now a Magnum Associate. Her portrait series, Listen: Giving Voice to Iranian Women, gives voice to restricted Iranian women singers. Images from this series were included in a retrospective of her work at the Atlas Sztuki Art Gallery in Poland. ”For me, a woman’s voice represents a power that if you silence it, imbalances society, and makes everything deform. I let the Iranian women singers perform through my camera while the world has never heard them.”

Indian storyteller, artist and activist, Poulomi Basu, challenges taboos with her advocacy for humane conditions for women in Nepal. Her multimedia project, Ritual of Exile, exposed the harsh and dangerous reality of the ritual of Chhaupadi, which forces menstruating women to live alone in mud huts away from their families each month. Basu witnessed the declining health of a 16-year-old new mother and arranged a life-saving trip to the nearest hospital. The young mother survived and Basu’s work is seen as contributing to the 2017 legislation criminalizing this degrading practice.

”For me, a woman’s voice represents a power that if you silence it, imbalances society, and makes everything deform. I let the Iranian women singers perform through my camera while the world has never heard them.”

—Newsha Tavakolian

Women are profoundly impacting photojournalism and documentary photography. No longer in the shadows, our storytelling is creating necessary change and questioning the structures of power, challenging constructs which exclude women. As British scholar and classicist, Mary Beard, proclaims in Women and Power: “If women aren’t perceived to be within the structure of power, isn’t it power itself we need to redefine?” Seeing through a woman’s lens captures an inclusive and humane truth, free from binary interpretations.

ZEKE Book Reviews

BOOKS REVIEWED IN THIS ISSUE:

- Welcome to Camp America: Inside Guantánamo Bay by Debi Cornwall

- MFON: Women Photographers of the Africa Diaspora co-edited by Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and Adama Delphine Fawundu

- Transcendents: Spirit Mediums in Burma and Thailand by Mariette Pathy Allen

- On the Frontline by Susan Meiselas

- Traces by Weronica Gęsicka

- Human Tribe by Alison Wright

Welcome to Camp America: Inside Guantánamo Bay

by Debi Cornwall Radius Books, 2017 Essays by Moazzam Begg and Fred Ritchin 190 pp./$50.00

At the United States military prison camp known as Guantánamo Bay detention camp, visiting photographers were welcomed, as long as they complied with pages of rules. No photos of faces or locks. Photographers were always accompanied by military escorts, who would sometimes move them and their cameras until something that should not be seen was out of view. During nightly reviews of memory cards, the authorities deleted any images that broke the rules, stated or unstated. The photographs that were left showed only views consistent with the prison’s mission statement: “Safe, Humane, Legal, Transparent.”

Debi Cornwall, a lawyer turned photographer, found brilliant ways to evade these restrictions of “transparency.” Her book, Welcome to Camp America, sketches the outlines of what cannot be shown by juxtaposing photographs of the areas of Guantánamo that hold detainees and “Camp America,” the recreational facilities for their guards. Stools pulled up to a tropical-themed bar contrast with a chair, laden with restraints, used during the force-feeding of hunger-striking detainees. A red plywood sleigh spray-painted with “Happy Holidays” perches on the roof of a life-sized gingerbread house, reinforcing the barrenness of a metal cage in detainee housing, holding only a folded prayer rug and a spray-painted arrow pointing towards Mecca. A sign printed with a reminder to call 911 “in case of emergency” hangs poolside, below a palm tree, reminding us that the detainees have no such recourse to aid.

The book also contains text, including excerpts from court documents in which guards have described the horror of detainee conditions. The photographs offer commentary on this text, as when the description of a cover-up of abuse is accompanied by an image of cleaning supplies. A photograph of the American flag printed on a trash can is even more bitter.

Photographers visiting Guantánamo could see detainees only during tightly controlled media tours. Conditions varied, but Cornwall reports that she saw detainees only through a two-way mirror. The military escort handed out bits of tape to the photographers to cover their cameras’ focus-assist light, which might otherwise let the detainees know they were being photographed. Rather than cooperating with depicting these detainees as “the worst of the worst,” Cornwall pointed out that hundreds of the men who were detained and tortured at Guantánamo were released after military commissions determined that they had been arrested by mistake or without any supporting evidence. She travelled to visit some of these former detainees, photographing them in collaborative creation, with their permission and in places of their choosing.

Cornwall visited Guantánamo during the Obama Administration. Since President Trump took office, the words “legal” and “transparent” have been omitted from the prison’s mission statement. Photographers who wish to follow in Cornwall’s footsteps must find new ways to show Guantánamo, one that no longer maintains even the pretense of being visible.

— Erin Thompson

MFON: Women Photographers of the Africa Diaspora

Co-edited by Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and Adama Delphine Fawundu Eye & I Inc., 2018 $40.00

MFON: Women Photographers of the Africa Diaspora is a revolutionary anthology of work dedicated to the memory of Mmekutmfon ‘Mfon’ Essien, a young, sharp and visionary Nigerian-American photographer who passed away in 2001. It is the beginning of an initiative that includes an annual publication and the establishment of the ‘MFON Legacy Grant’ which will be awarded to emerging black women photographers of African descent. The closest black women photographers have had to this in the past thirty years is Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe’s 1986 Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers that documented the contributions of black female photographers in the United States. ‘MFON’ goes further and broader by encompassing women photographers of the African diaspora all around the globe and including essays written by women scholars, journalists and artists.

The result of this is an impressive record of photographers of ages ranging from 13 to 90, from Madagascar to Arkansas, Johannesburg to London, Stockholm to Chicago, working across different genres from fine art to commercial photography. It is, however, not a comprehensive survey or a complete history of black women photographers, and neither was it intended to be. Instead, it includes a cross-section of images selected to frame stories about freedom, justice, belonging and repossession of selfhood. Roaming through the over 100 photographs included in this anthology is the gaze of the black woman in diaspora, revealing what she sees, the questions she asks and the ways she imagines and reimagines the world. Many of the women in this book focus their cameras on their own bodies, families and communities, and some of the rites and rituals that come with these possessions from religion to motherhood, food, sexuality and the subject of black hair, beauty and fashion. Some look out, interrogating the boundaries of blackness and others look at celebrity figures and socio-political phenomena shaping our world today. These are essays and photographs bearing voices that are often ignored, not taken seriously, or not given the opportunity to develop and their presentation evokes links across the African continent and diaspora. This is an anthology that understands that who we are depends on how we see and are seen.

Agency, community and possibility are the currents running through this book and it pulls on this current by anchoring its focus on self-portraiture: the practice of including one’s self and history in the well of narratives, literally and symbolically. Beside the inspiring talent it showcases, this book is important because representation matters, especially when it’s one brimming with possibility; one that squarely says, especially to women photographers of the African diaspora: “you can be, be and be better.” It is “a love letter to lovers of photography, black women, women of African descent, those who show up, those who are present, lens folk,” as Laylah Barrayn says in her editor’s note.

—Immaculata Abba

Transcendents: Spirit Mediums in Burma and Thailand

By Mariette Pathy Allen Essay by Eli Coleman, PhD. Preface by Zackary Drucker Daylight Books 142 pp./$45.00

For Transcendents, her fourth book exploring the lives of gender non-conforming people, Mariette Pathy Allen turns her lens on the spirit mediums of Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand.

Allen is an artist and activist who has been documenting gender variance for decades. Her first book, Transformations: Crossdressers and Those Who Love Them (E.P. Dutton) was published in 1989. Since that time, she has continued to focus on the transgender community, and brings to her work the benefit of a decades-long immersion. As such, her images are not voyeuristic, nor do they seek to be sensational. In the preface, Zackary Drucker, transgender LGBTQ activist and producer of the television series “Transparent,” notes that the power of Allen’s documentation of trans and gender nonconforming lives is in the way it quietly shows “trans folk living among their fellow country-people, fully integrated into the fabric of their communities and living openly…”

In the communities in Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand that Allen photographed over the course of four trips, she captured individuals who serve as mediums to the spirit world. The two countries share a similar culture of Animist spirit worship that coexists with the predominantly Buddhist culture. Mediums are the messengers to and of the spirits—who are called upon for guidance and favors. Transgender and gender nonconforming men are increasingly stepping into the esteemed role of medium that traditionally was held by women. In so doing they find a means of expressing their gender identity while also earning the respect of their families and communities.

Burma and Thailand share a traditionally homophobic and transphobic culture. It is all the more powerful, therefore, that these individuals have found a role within the context of their cultures that allows them to flourish and to be fully integrated into their communities. Allen’s collaborator, Eli Coleman, PhD., professor and director of the Program in Human Sexuality at the University of Minnesota, remarks on the way in which Allen’s photographs “show how the status of transgender individuals is socially constructed and more or less stigmatizing, depending on the context.”

Allen has an MFA in painting and has brought this sensibility to her photographic work: She seems to delight in layered, saturated color. Transcendents contains 75 plates, which are a mix of portraiture and documentary-style photographs of mediums mid-ceremony. These are punctuated by a handful of still lifes and landscapes that are intended to put the other images in the context of their geographic and cultural setting. The portraits have a certain formality to them; they are not intimate, but rather, are politely distant and respectful. You sense that the subjects had a hand in composing them. There are only a few photographs that capture in-between moments—a medium painting their nails on the seat of their motorcycle, applying makeup, or enjoying a glass of wie. These glimpses add another dimension to the story, and leave the viewer wanting more of them.

Taken together, the photographs of Transcendents tell a story of both the unique mystery of the mediums’ spirituality and—equally important—of the mundane and unrmarkable apects of their everyday lives as members of their communities.

—Jenna Mulhall-Brereton

On the Frontline

by Susan Meiselas Aperture 2017 256 pp./$29.75

Susan Meiselas’s On the Frontline is not so much a photo book as an illustrated consideration of what photographs can and should do, framed by the career of a hugely influential photojournalist, writer, activist, curator, and educator. Some of Meiselas’s images have entered popular memory as archetypes and symbols. She has long held leadership roles among the people and institutions that link documentary practice with social justice. Meiselas’s thoughtful description and analysis of her practice is the result of some 40 years of making pictures and thinking about them, while also trying to make sense of the larger world and her responsibilities to it.

The book’s opening images show the forensic unearthing of mass graves that Meiselas documented in Kurdistan in 1991. As front matter, they resonate as metaphor for the relentless digging into the past that characterizes Meiselas’s work. Her pattern of returning over decades to a place she photographed is a way of recognizing that photographs are slippery and the story is ongoing, but it also lets her acknowledge that her past work there is now a part of multiple histories of a place that merit continuous re-consideration.

The bulk of the book is a careful blending of words and images that investigate the idea of narrative as the link between Carnival Strippers and Kurdistan, Prince Street Girls and the Dani, Nicaragua and scenes of domestic violence. Each story is told of and with the people the photographs depict, but these stories extend well beyond the frozen photographic moment to include past and future and multiple perspectives. From her earliest photojournalism to recent experiments in publication and installation, Meiselas has sought ways to help those who are often voiceless tell their stories. On the Frontline is notable because it affirms both why and how this must be done.

Everything about this book encourages us to weight words and pictures equally. The book is small and in vertical format, to be held in the hands rather than displayed on a coffee table. A third of the pages are text; her photographs, while thoughtfully chosen and sequenced, are de-emphasized by reproductions that demand less attention than the lavish prints we have come to expect in art books. Meiselas’s words are direct, open, conversational, and considered, a tribute to the interview format from which the essay is derived, and the skill, sympathy and intelligence of Mark Holborn, interviewer and editor.

I can’t think of another photographer’s memoir that so rigorously considers picture-making as a practice with intellectual, aesthetic and moral dimensions. This is an essential book for photographers, theorists, historians and others who care about pictures, not just for what they look like but for what they do.

—Alison Nordström

Traces

By Weronika Gęsicka J. & W. Ge˛sicka, M. Sokalska, 2017 64 pp. / $35.00

Somewhere along the way we collectively decided that the 1950s and 60s were the heyday of the American Dream. Despite the fact that the era was rife with racism, sexism, war, and myriad other issues, photographs of that time conjure up notions of suburban idealism: two-parent households with freshly scrubbed kids, cold glasses of milk, and warm slices of apple pie.

Traces by Weronika Gęsicka upends such rosy-colored memories, slicing them apart and rearranging them so the fragments become a Frankensteinian version of history—a monstrous reimagining of a sugar-coated past. Using stock photographs from the 1950s and 60s, Gęsicka deftly manipulates the content, reworking mundane commercial imagery of happy families and young lovers in a variety of situations—mowing the, lawn, roasting marshmallows, and sitting around the dinner table—into surreal tableaus that underscore the fear and anxiety that permeated the time.

Post-war America may have been prosperous and victorious, but the specter of WWII still loomed over the country and fear of Communism, homosexuality, desegregation and civil rights, and the war on drugs permeated the nation’s conscious. Anxiety was at the forefront of the medical and psychiatric fields, and self-medication was rampant given the accessibility of alcohol, tobacco, and prescription drugs (not to mention the use of illegal drugs like heroin and marijuana). However, along with these anxieties came the rise of American commercialism, which promoted ideals such as the nuclear family and the American Dream as existing in symbiosis with luxury cars and household goods. In the midst of a sea of uncertainties, the obvious antidote seemed to be spending money.

Gęsicka’s photographs dissect the relationship between ideological consumerism and societal ills. In one photograph, soda shop patrons are swallowed up by the shop’s interior, engulfed by the countertop and the interior’s wood paneling and wallpaper. In another, children run down the front sidewalk of a house toward their father’s outstretched arms, except a portion of the sidewalk is missing, indicating that they are instead running towards their deaths. The images are at once funny and haunting, the sort that make you chuckle and shake your head while sending shivers down your spine. Through her darkly playful reimagining, Gęsicka exposes the machinations of the collective desire to escape the terrifying traces of our past. Do we even know who we are or where we have come from, or are we better off pretending we are something else?

—Danielle Avram

Human Tribe

by Alison Wright Schiffer Publishing, 2017 180 pp /$29.99

Alison Wright’s fifth photography book, Human Tribe, takes viewers through an immersive journey into the unified experience of human life around the globe. With every turn of the page, viewers are confronted with a new face from a different part of the world. Wright writes in the introduction of the book that her intention with these portraits is to reflect the complexity and beauty of humanity, while highlighting our common desires and needs as humans on earth.

Wright has a distinct documentary style, producing frames that lend each portrait a unique character. Each person shares a part of themselves. Their eyes communicate a story—some warm, some intense, some vulnerable, but each shared with intention. The colors maintain a vibrant thread throughout the book. Whether through a beaded necklace, a cigar hanging out of an older man’s mouth, or luminescent water reflecting in the background, each person’s story is amplified by the colors captured in the frame.

The author compliments her stunning portraits by positioning the photos with nuanced coordination, continuing a narrative and conversation between the subjects. On page 68 and 69, Wright positions a photo of a toddler leaning into another baby’s crib in juxtaposition with a middle-aged man and woman dancing in Buenos Aires, mirroring the posture of tango. Aligned together, these two narratives of movement explore the ways we express human energy. Page 48 and 49 show a middle-aged man posing in a straight-on portrait in Lanzhou, China opposite a young boy from Omo Valley, Ethiopia. Each gazes straight into the viewer’s eyes. While the older man wears big circular glasses made with smoothened plastic and glass frames, the young boy’s similar round glasses seem to be self-made of styrofoam and wire—both are looking through a lens to view the world. Wright’s intentional sequencing of bold colors magnifies the synchronicity and unity of human experiences.

Human Tribe furthers Alison Wright’s unique ability to reveal individual essence and offer insight into our shared human experience. She accomplishes her goal of capturing the diversity of human life and she does so with an exquisite eye.

—Nayo Sasaki-Picou

Contributors and Resources

Photographers

Casey Atkins currently works in the Boston area as a freelance photographer and filmmaker. She is a member of both the Boston Press Photographers Association and the National Press Photographers Association, as well on the board for the New England chapter of the American Society of Media Photographers.She is also a director of Women’s Worth, Inc., a nonprofit which provides business skills training to low-income women in Nicaragua.

Delphine Blast is a French documentary and portrait photographer, based in Bolivia. She works on various issues related to development with a strong focus on women’s issues in South America.

Amber Bracken is a member of Rogue Collective and a lifelong Albertan. Her interest is in the intersection of photography, journalism, and public service with a special focus on First Nations People.

Joan Lobis Brown is a photographer whose portrait projects highlight segments of our society that have been subjected to intense stigma.

Vidhyaa Chandramohan is an editorial & documentary photographer from India, currently based in Abu Dhabi. Her long-term projects delve into women-related projects/issues, human rights and gender identity.

Jean Chung is an award-winning photojournalist based in Seoul, South Korea who gained international recognition with her series of photo-reportage in Afghanistan and Africa.

Anica James is a documentary photographer and photography instructor currently based in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada. She is a member of Muse Projects and Women Photograph.

Susan Kessler is a practicing architect turned documentary photographer who is most passionate about photographing for organizations that positively impact the lives of women and children in developing countries.

Heba Khamis is an Egyptian storyteller whose work concentrates on social issues that are often ignored.

Valerie Leonard travels the world following her theme, “Labours of Hercules,” a series of photographs that attempts to show with utmost respect the dignity of women and men living and working in hostile environments.

Amy Martin uses her camera’s lens to increase awareness, understanding and compassion across physical and social barriers.

Marinka Masséus’s photography revolves around people and is a constant reflection of her passion and fascination for human nature and the way we live our lives. Topics concerning injustice and gender inequality are a driving force behind her work.

Emily Schiffer is a photographer and mixed media artist interested in the intersection between art, community engagement, and social change.

Maranie Rae Staab is a Pittsburgh-based, independent photographer and journalist working to document human rights and social justice issues, displacement and how violence and war affect individuals and societies.

Danielle Villasana is an independent photojournalist whose documentary work focuses on women, identity, human rights, and health. She is currently based in Istanbul and contributes to Redux.

Beata Wolniewicz is a Polish photojournalist and documentary photographer, who has travelled to many countries including Georgia, Ghana, Israel, Lebanon, USA, Poland and many European countries.