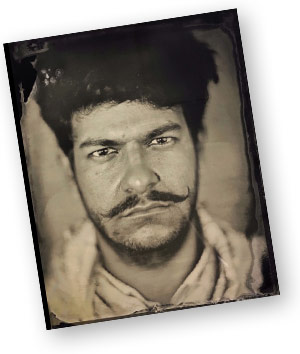

Interview with Furkan Temir

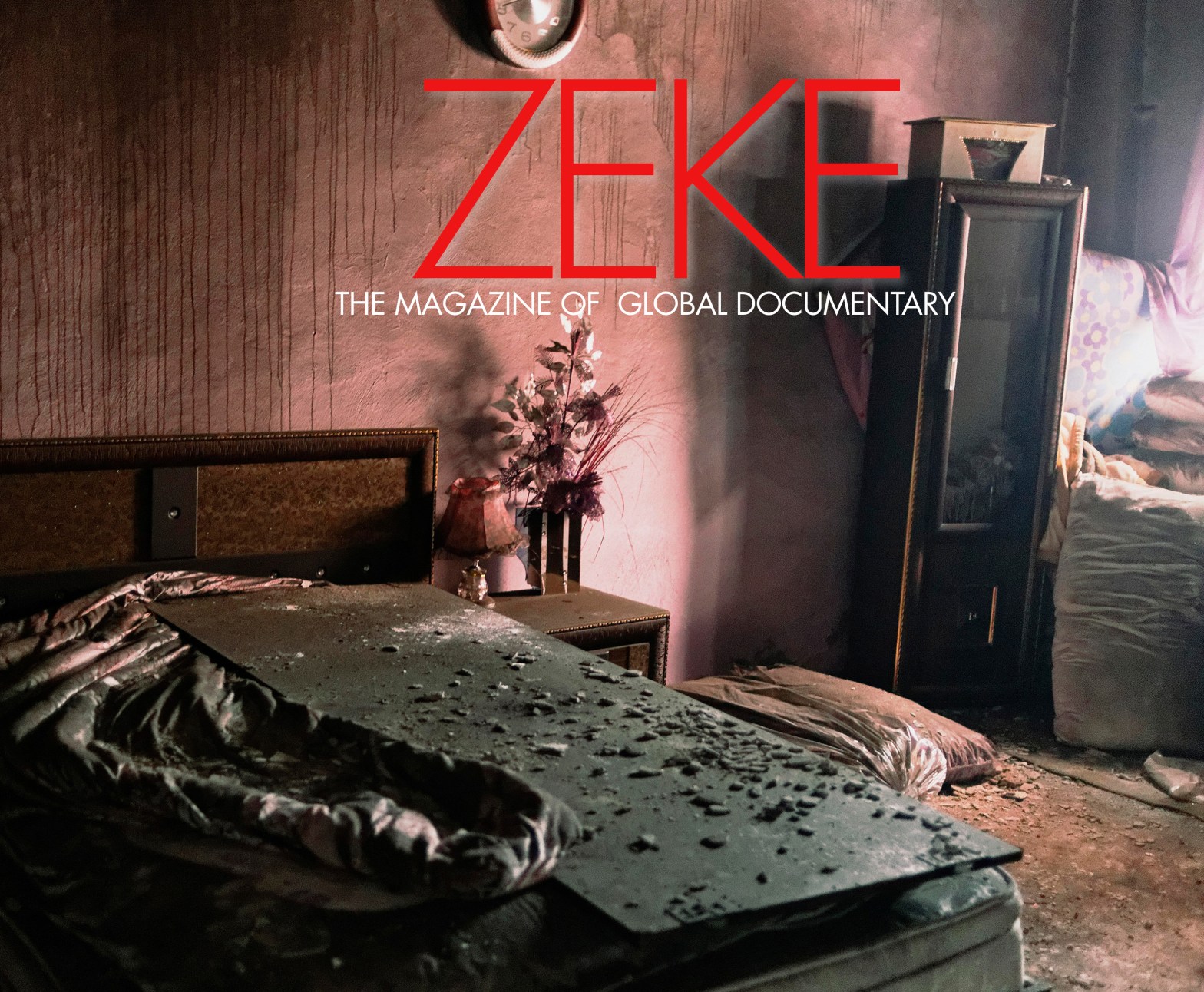

by Caterina Clerici, from the spring 2017 issue of ZEKE magazine

Furkan Temir is a self-taught Turkish photographer, born in a small town in eastern Turkey in 1995. He is currently living in Istanbul and is a member of the VII Mentorship Program. Interested in photojournalism as well as art, he uses mixed media to create documentary work on the Middle East, particularly focusing on socio-political changes in contemporary Turkey.

Caterina Clerici: How did you become a photographer?

Furkan Temir: I was born in a really small town in eastern Turkey. When I was 7, I went to the cinema in the city center, and for the first time in my life, I saw the cinema screen. That’s when I decided I wanted to make movies. My mother was a literature teacher and she told me if I wanted to make movies, I had to read a lot. So I became really obsessed. When I was 14, I was reading Tarkovsky’s cinema theory and he was always talking about the frame. I understood that if I wanted to make movies I had to learn photography as well, but I was so young and didn’t have a camera. So I started looking at photos on the internet — three or four hours a day. I became obsessed and almost watched everything in the archives of the agencies.

CC: What drew you to photography?

FT: I understood that photography can give me a chance to understand the world and to travel, it can connect with reality. When I started getting into photography, art photos or artistic pictures were a bit too far away from me, I was really young, so I decided I wanted to go into photojournalism.

CC: What was your first photojournalism project?

FT: We moved to Boursa [in Turkey] and I started to document my little city and the things happening there. Then, the Gezi Park protest happened and that was the first time I worked as a professional photographer. I was working for a Turkish photo collective, Agence Le Journal, and my photos were published in TIME, The Guardian and Stern. After the Gezi Park protest, I went to Syria in 2013 for the first time. The war was just starting at that time. I was 17, and I was 18 the first time I went to Iraq. I have made several trips to Syria and Iraq since then.

CC: What made you want to cover the events in Syria? I read in an interview you did with the New York Times’ Lens Blog that one day you told your family you were going to school and instead you went to Syria.

FT: My aim was documenting the refugees on the border, how they arrived, what they were doing. Then I met with a few guys who knew some smugglers and asked me if I wanted to go to Syria. I said yes and I went.

CC: What about the first time you went to Iraq?

FT: In Iraq, my aim was going to Kirkuk. At this point, there was a fight between the Kurdish Peshmerga and ISIS, and I had a small assignment from Le Monde. I was going to the frontline.

I strongly believe that photography can change things. … When you see the front page of the New York Times, like millions and millions of other people every day, maybe just one person looking at that picture and feeling something will bring change.

—Furkan Temir

CC: Is it harder for you to be objective and detached when working on the frontline or with refugees from a conflict that affects you a lot more than it does to any Western photographer, who doesn’t necessarily relate in the same way to the grievances and the politics of the region?

FT: It isn’t really hard. With the Peshmerga, for instance, I was spending all my time with them because I didn’t have assignments or money, and because the only way to take these pictures was living with them. I am not sure if I was objective or not, but I’m sure I was inside the story, and I tried to protect the photojournalism ethics of course.

CC: Was it harder to document the suffering of people who were really close to your home?

FT: Absolutely. Syria and Turkey share a border which is drawn by the governments. I don’t see this border. For me, Iraq and Syria are close to my home.

CC: What were the most interesting stories or people you met there?

FT: On the Syrian border, I saw a funeral, the only one I had seen after my grandfather’s. It was a really strange thing because I was crying for other people that I didn’t know, but I felt their pain. And I feel like it was a really similar pain to my grandfather’s funeral. This was a bit hard. It became impossible to stop crying as I was shooting because it was too intense and these people were also giving me access to shoot some photos [in a moment of grief].

CC: Have you kept in touch with some of these people?

FT: Not in Syria or Iraq, but I did with some of them in Turkey by chance. In 2015, I was in the Newroz celebration. It’s the biggest spring celebration for Kurds and it also has a political meaning. At this moment in Cizre, the Newroz celebration was so big. One year after, when I went back to document this celebration again after the war between PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) and the Turkish army, and reconnected with a few civilians I had met there the year before. This time, half of the city was totally destroyed.

CC: Why are you so interested in covering the Middle East and the area where you’re from?

FT: I’m more connected to this region because I was born here and I grew up here. I’m still so young; I would like to understand my region first, and then in the next couple of years, I would like to travel out of the Middle East as well.

CC: You started off being interested in cinema, so you’ve always been interested in working with mixed media. Has your idea/vision of photojournalism changed, and are you shifting more towards artistic photography?

FT: I see myself as a storyteller and I’m trying to use all the techniques that I find to express myself. At this period of my life I am painting a lot, and my current documentary project, which I started a year ago, includes more artistic photography and video. It’s about the idea of Turkish Paradise and the post-truth era in Turkey — how a new vision of the country and its society is being pushed forward. I’m using the term ‘post-truth’ for its political value, but the project is about aesthetics and architecture. After the AKP (Justice and Development Party) party won the election in 2003, they tried to shape Turkey politically but also breaking from the past to create an ideal society with a new architecture and aesthetics. My project focuses on these changes all around Turkey. They renovated everything and built things anew. I’m trying to understand the story behind it and how these aesthetic changes affect people’s lives.

CC: Is this a way to literally fabricate, and impose, a new vision of society?

FT: Actually, I don’t know. My aim was to give answers, but I have even more questions now. It’s a very contemporary journalism project — it’s mixed media with archives, some new media works from Google Earth, some archival pictures, some black and white and some colors. It’s really mixed. I’m just putting everything on the table with a lot more questions.

CC: Do you think that photojournalism has lost its power, since people are so used to seeing those types of images, and that maybe art can sometimes convey a stronger message?

FT: I do, but I also strongly believe in ethical journalism and I love it as a way to tell stories. I’m mixing [media] because I’m born in this new age, with these new rules, and I wouldn’t know another way of approaching this profession. I was born in 1995 and I’ve grown up with computers, so I have to use VR and mix new technologies to tell more powerful stories. But it doesn’t take away from classical photojournalism. These are just tools.

CC: After spending a few years working in photography, do you still think it holds the power to change things?

FT: I strongly believe that photography can change things. First of all, it’s an action. Every act in the universe has some sort of consequence. It’s impossible not to change at least something. Maybe it can be hard to see with our eyes, but look at history. Maybe it’s not changing today, but I’m sure someone will be affected in the future. When you see the front page of The New York Times, like millions and millions of other people every day, maybe just one person looking at that picture and feeling something will bring change.

N.B. This interview was edited for clarity.

Masthead

ZEKE is published by Social Documentary Network (SDN), an organization promoting visual storytelling about global themes. Started as a website in 2008, today SDN works with more than 1,500 photographers from around around the world to tell important stories through the visual medium of photography and multimedia. Since 2008, SDN has featured more than 2,000 exhibits on its website and has had gallery exhibitions in major cities around the world. All the work featured in ZEKE first appeared on the SDN website, www.socialdocumentary.net.

Spring 2017 Vol. 3/No. 1

ZEKE Staff

Executive Editor: Glenn Ruga Editor: Barbara Ayotte Interns: Kelly Kollias, Laney Ruckstuhl

Social Documentary Network Advisory Committee

Barbara Ayotte, Medford, MA Senior Director of Strategic Communications Management Sciences for Health

Lori Grinker, New York, NY Independent Photographer and Educator

Steve Horn, Lopez Island, WA Independent Photographer

Ed Kashi, Montclair, NJ Member of VII photo agency Photographer, Filmmaker, Educator

Reza, Paris, France Photographer and Humanist

Jeffrey D. Smith, New York NY DirectorContact Press Images

Molly Roberts, Washington, DCSenior Photography EditorNational Geographic

Steve Walker, New York, NY Consultant and educator

Frank Ward, Williamsburg, MA Photographer and Educator

ZEKE is published twice a year by Social Documentary Network Copyright © 2017 Social Documentary Network Print ISSN 2381-1390 Digital ISSN: Forthcoming

ZEKE does not accept unsolicited submissions. To be considered for publication in ZEKE, submit your work to the SDN website either as a standard exhibit or a submission to a Call for Entries. Contributing photographers can choose to pay a fee for their work to be exhibited on SDN for a year or they can choose a free trial. Free trials have the same opportunity to be published in ZEKE as paid exhibits.

To subscribe: www.zekemagazine.com/subscribe

Advertising inquiries: glenn@socialdocumentary.net

Photographers and writers featured in this issue of ZEKE

Anna Akage-Kyslytska, Ukraine

Azad Amin, Iran

Sarah Blesener, United States

Emma Brown, United States

Caterina Clerici, United States and Italy

B.D. Colen, Canada

Nikki Denholm, New Zealand

Ariz Ghaderi, Iran

Saeed Kiaee, Iran

Kelly Kollias, United States

Mehdi Nazeri, Iran

Paolo Patruno, Italy

Laney Ruckstuhl, United States

Anne Sahler, Germany and Japan

Sadegh Souri, Iran

Frank Ward, United States

Social Documentary Network61 Potter Street Concord, MA 01742 USA 617-417-5981 info@socialdocumentary.net www.socialdocumentary.net www.zekemagazine.com @socdoctweets

Cover photo by Mehdi Nazeri from Poverty in Wealth. Bandar Abbas, Iran.

Sponsors