The doctor who discovered AIDS

In the spring of 1981, a Rochester-trained physician made a discovery that would launch a new chapter in medical history, and set the course of his career.

by Karen McCally ’02 (PhD)

Michael Gottlieb was just a few years out of his internal medicine residency at the University of Rochester when he made medical history as the first physician to identify and describe the disease that soon after became known as acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

“I remember those first patients in great detail,” Gottlieb told a Medical Center audience in November 2015. “I remember what they looked like. I remember certain mannerisms of those first patients in far greater detail than patients I saw last week. I remember the courage with which they faced the unknown.”

Gottlieb, who earned his MD in 1973 at Rochester before completing his residency training at the School of Medicine and Dentistry, was in his first year as an assistant professor of immunology at UCLA when he asked one of his fellows to look for some interesting teaching cases—the kind who had “immunologic features that might be interesting to talk about on rounds,” Gottlieb later recalled. The fellow brought him Michael: a 31-year-old man, healthy just weeks before, who had arrived in the emergency room reporting severe weight loss, loss of appetite, and a persistent fever.

Michael had thrush coating his mouth and esophagus, while his white blood cell count was abnormally low—a sign of a failing immune system. A week after his initial emergency room visit, he was readmitted with Pneumocystis carinii, a rare lung infection then seen only in people with severe immunosuppression, such as victims of starvation. Gottlieb said it was “shocking” to see someone, essentially coming in off the street, with the infection.

His report was the first clinical description of AIDS. And its date—June 5, 1981—marks the official start of the AIDS epidemic.

Three months later, in April 1981, Gottlieb and his colleagues at UCLA had identified four cases similar to Michael’s, all in the Los Angeles area. Gottlieb noted a few things in common about the patients. They had all been healthy until recently, and they were all sexually active gay men.

“At first I thought the immune deficiency in these patients might actually be reversible,” Gottlieb told the same audience in 2015. “Our first four patients were gay men. Is it possible they had some common exposure to a drug or a toxin?” He wondered if the reversal might come about naturally, as the immune system recovered.

The patients continued to deteriorate, coming down with multiple infections. Gottlieb notified the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and in June, published a nine-paragraph report, “Pneumocystis Pneumonia—Los Angeles,” in the CDC’s newsletter, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The report was the first clinical description of AIDS. And for the purposes of tracking AIDS cases, the date of Gottlieb’s report—June 5, 1981—marks the official start of the AIDS epidemic.

Following a synopsis of each of the five patients, Gottlieb wrote in the report, “All the above observations suggest the possibility of a cellular-immune dysfunction related to a common exposure that predisposes individuals to opportunistic infections.” Tests on the patients showed infections present in semen, but not in urine, leading Gottlieb to speculate that “seminal fluid may be an important vehicle” of transmission.

Gottlieb’s brief report launched not only a new era in medical history, but also the arrival of what would become the physician’s calling. Gottlieb, who treated Rock Hudson following the actor’s explosive announcement in 1982 that he had AIDS, has continued to treat AIDS patients ever since. Cofounder in 1985 of the American Foundation for AIDS Research, Gottlieb has been a leading advocate for AIDS research and treatment for 35 years.

Much was still unknown following the identification of AIDS. It wasn’t until 1983 that French researchers discovered the virus HIV as the cause of AIDS.

For a long time, AIDS was also assumed to be primarily a disease of gay men in modern urban enclaves. Thirty-five years later, it’s well known that that’s not the case. Activist-led public education campaigns in the 1980s and 1990s proved remarkably effective in reducing HIV transmission in gay communities in the United States—although in 2001, those rates began to rise again. Today more than 9 out of 10 cases of HIV are among men, women, and children in developing nations.

More than 30 years, 78 million cases, and 35 million deaths later, Gottlieb is optimistic that AIDS can be overcome, most likely through a vaccine.

But it will also take more than even the discovery of a vaccine or a cure. Writing on the 25th anniversary of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Gottlieb made an observation that’s no less true today: “I believe overcoming AIDS means extending our medical progress to everyone—and that’s a tall order.”

Magic Johnson’s HIV bombshell

It’s been 25 years since NBA superstar Magic Johnson announced his HIV diagnosis to the world. How did that event change public perceptions of the disease? And how far have we come since then in addressing the HIV/AIDS public health crisis? We talk to LaRon Nelson, assistant professor of nursing and associate director of international research at the University’s Center for AIDS Research.

Rochester Researchers Leading the Way

The University of Rochester has a long history in HIV research, and was one of the first sites in the United States to conduct HIV vaccine studies. The National Institutes of Health-sponsored University of Rochester HIV/AIDS Clinical Trials Unit, also known as the Rochester Victory Alliance, has participated in more than 275 HIV treatment and vaccine trials and enrolled upwards of 3,500 volunteers since 1987. They are currently testing a new method to prevent HIV called “antibody mediated prevention” in high risk populations, including black men who have sex with men and transgender individuals who have sex with men. Scientists are hopeful that this study will boost the development of an effective vaccine for the virus.

The University of Rochester is also home to the UR Center for AIDS Research, one of just 20 sites in the country designated by the National Institutes of Health to enhance collaboration and coordination of HIV/AIDS research. Members of the UR CFAR are conducting a wide range of studies, including: early laboratory research on how HIV-associated inflammation leads to problems with cognition and dementia; and how the use of mobile technology can break down barriers to care by improving communication between patients and health care providers and allowing for the development of personalized treatment plans.

For the second consecutive year, the River Campus Susan B. Anthony Center has combined forces with the UR Center for AIDS Research and the Rochester Victory Alliance to light the city of Rochester red in observance of World AIDS Day. The number of buildings and landmarks participating in this event nearly doubled since last year. High Falls, Kodak Tower, Rundel Memorial Library, Eastman Museum, and many other famous buildings will go red to raise community awareness of HIV.

“The real fight against HIV takes more than just a doctor or a pill,” said John P. Cullen, PhD, Assistant Director at the Susan B. Anthony Center, which focuses on community engagement, particularly translating research into policies that benefit the public. “It begins with awareness, education to end stigma and discrimination and getting more people involved in research and other efforts to end the epidemic.”

When NBA superstar Magic Johnson announced his HIV diagnosis to the world 25 years ago, the virus was considered an imminent death sentence. But progress in the treatment of HIV/AIDS has been remarkable by any measure. Johnson is not only alive today, but at 57, leading a full life that includes work as an activist for HIV research, prevention, and treatment.

According to LaRon Nelson, an assistant professor at the School of Nursing, Johnson helped “increase people’s awareness that there was treatment available, and that people that we look up to were people who were also diagnosed with HIV.”

Nelson, who earned both is undergraduate and doctoral degrees from the School of Nursing, is currently the Dean’s Endowed Fellow in Health Disparities and a noted expert on HIV/AIDS disparities in both treatment and prevention. In 2011, when he was an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, the Canadian government named him one of 19 Rising Stars in Global Health. Earlier this year, the Ontario HIV Treatment Network chose him as its inaugural research chair in HIV program science for African, Caribbean, and black communities.

Nelson says that in spite of Johnson’s highly publicized work, HIV still carries a stigma in many communities and cultures. That stigma is among the most stubborn barriers to accessing HIV treatment. “Because of stigma, many times people won’t walk through the [health clinic] door,” Nelson says.

In an effort to reduce the fears of stigmatization and offer more access to information and care, Nelson is studying the use of mobile apps that offer resources outside traditional clinical systems.

Representing AIDS, then and now

Interview by Kathleen McGarvey

Although AIDS is no longer the subject of his work, art and cultural critic Douglas Crimp—the Fanny Knapp Allen Professor of Art History and a professor of visual and cultural studies—played a central scholarly role in the first two decades of the AIDS crisis. He examined how we think and talk about the disease and people directly affected by it, the language we use, our ideas about science and medicine, our conceptions of public and private, and our notions of health and illness, sex and death.

In 1987, Crimp—then a coeditor of the art journal October—put together a special issue titled AIDS: Cultural Analysis, Cultural Activism, a series of critical essays on the culture of the disease. MIT Press published it as a book a year later, the first book-length treatment of the cultural meaning of AIDS. He followed with two other books on AIDS: AIDS Demo Graphics (Bay Press, 1990) and Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics (MIT Press, 2002).

Crimp also took his ideas off the page and into the world of activism, as a member of the group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT UP.

In the early days of the AIDS epidemic, you wrote that we can’t know AIDS apart from our representations of it. What did you mean?Any entity, or any question, is something that we know through our various means of knowing—language, scientific inquiry, the way we apprehend it through its media representations. And certainly in the early days of AIDS, when it was a kind of mystery, I—and those of us who were immediately affected by it—became especially attentive to the ways it was represented, in terms of trying to understand what this new disease that people were getting could be, the hysteria that surrounded it, and the ways that people were being represented in the media. Of course, that included gay men, of whom I’m one.

The ways that our lives were affected [by AIDS] were so dependent on a whole array of representations. So that statement is a provocative one—but it really matters how something is represented.

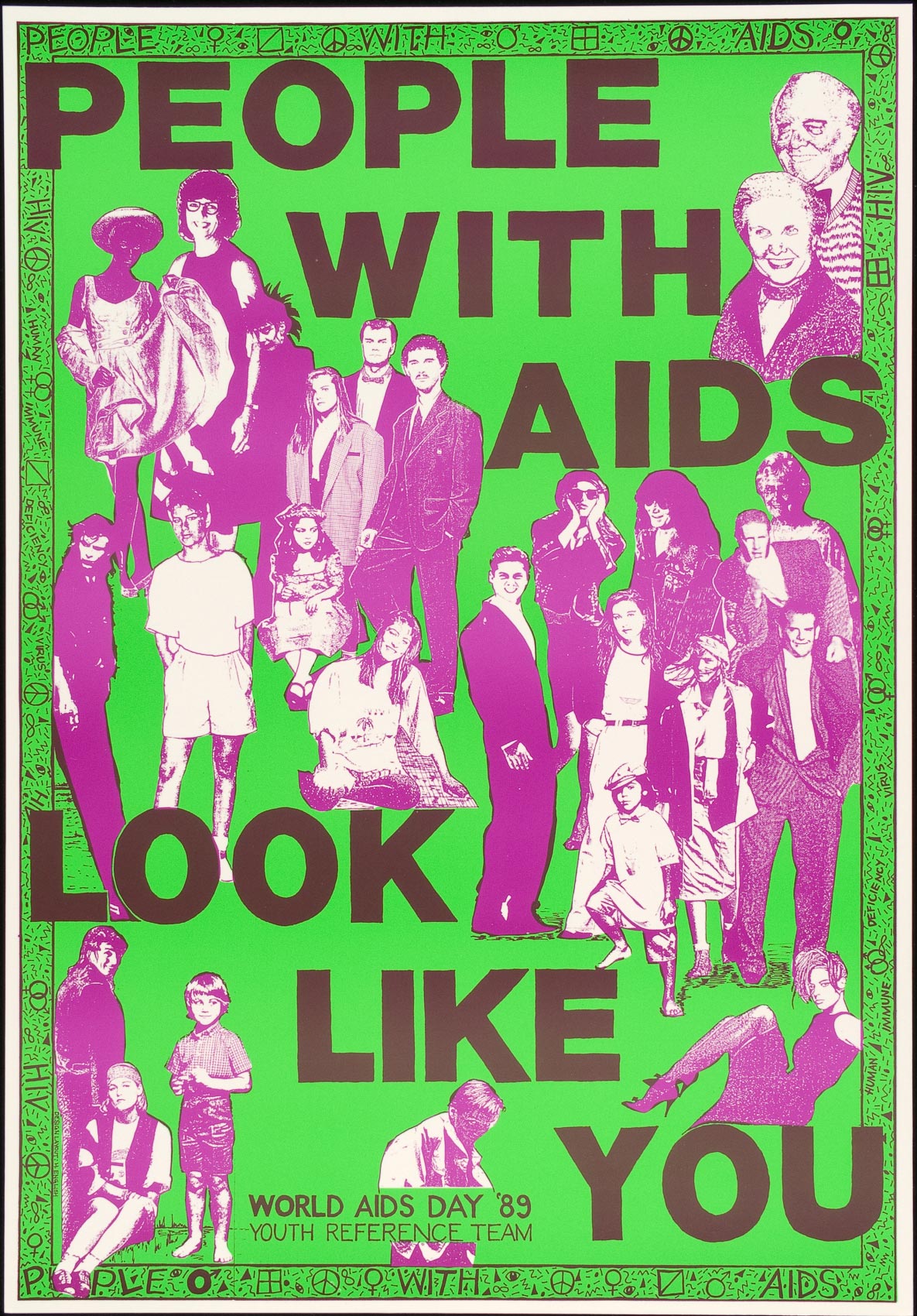

Early on, some people argued that AIDS might inspire great art, but that art had no explicit social role to play in fighting the epidemic. You countered that claim, calling for an “activist aesthetic practice,” in which art could help save lives by intervening in the social world. “We don’t need to transcend the epidemic; we need to end it,” you wrote in 1987. How was that received?There was a lot of controversy about my demand for activist art practices, and my apparent hostility to what I called “elegiac ones.” I revised that position pretty quickly. My book Melancholia and Moralism is a collection of everything I wrote on AIDS. Included in that book is the first essay I wrote after the special issue of October, called “Portraits of People with AIDS.” It was, again, quite polemical, opposing what I thought were phobic images of people with AIDS and supporting other kinds of images of people with AIDS, including a video called Danny by Stashu Kybartas, a beautifully elegiac work about a person who died of AIDS. So already I was aware that there were other important means of responding to the epidemic that were not so obviously activist.

What do you think of how AIDS is represented now?That’s a really complicated question. It’s not so much represented in the culture now, of course, and that’s a problem. We still have a very active epidemic in this country and in the world. And the degree to which there is still an enormous amount of transmission has to do in part with the fact that it’s not something that people—including the media—pay attention to.

The people in this country who are disproportionately affected are still gay men, particularly gay men of color, and IV drug users. And a lot of the men who transmit the virus to other men don’t identify with the kind of mainstream gay culture that is widely represented now, which purports to be a culture of marriage and of committed relationships. It’s no longer one of sexual promiscuity, even though promiscuity is very much alive and well in the culture.

One way that one could imagine AIDS receiving the wide public recognition that it needs at this point is if it were linked to what we in the activist movement demanded: “health care as a right.” AIDS is an issue in the same way all kinds of health problems are an issue. If you have HIV and are lucky enough to have health insurance, you will perhaps be able to get one of the enormously expensive drugs, drugs that might cost about $10,000 to $12,000 a year. AIDS is one of the preexisting conditions [that the Affordable Care Act requires insurance companies to cover]. But now Donald Trump has been elected president and the Republicans will control whether or not the Affordable Care Act survives, or survives in any form that makes it at all effective.

Do you think How to Survive a Plague, the new book by David France that chronicles the work of groups such as ACT UP (and the documentary film of the same name that preceded it) will help bring AIDS back to wider public consciousness?How to Survive a Plague concentrates on one very particular aspect of what we as activists did—changing the drug approval process and speeding up availability of the drugs that actually did save people’s lives. But it’s only one aspect of what we did, and it misses wider questions, particularly about income inequality and access to health care in this country. The book is going to get a lot of attention, and that’s fine. It will bring AIDS back into consciousness, but it will bring it into consciousness in a very particular way—as a heroic story of AIDS activists. The people at the center of the film are all white, but that wasn’t the composition of the movement itself. And there were many more issues in the AIDS activist movement than France took on, including homelessness and AIDS. And activists changed the way that people with AIDS were regarded.

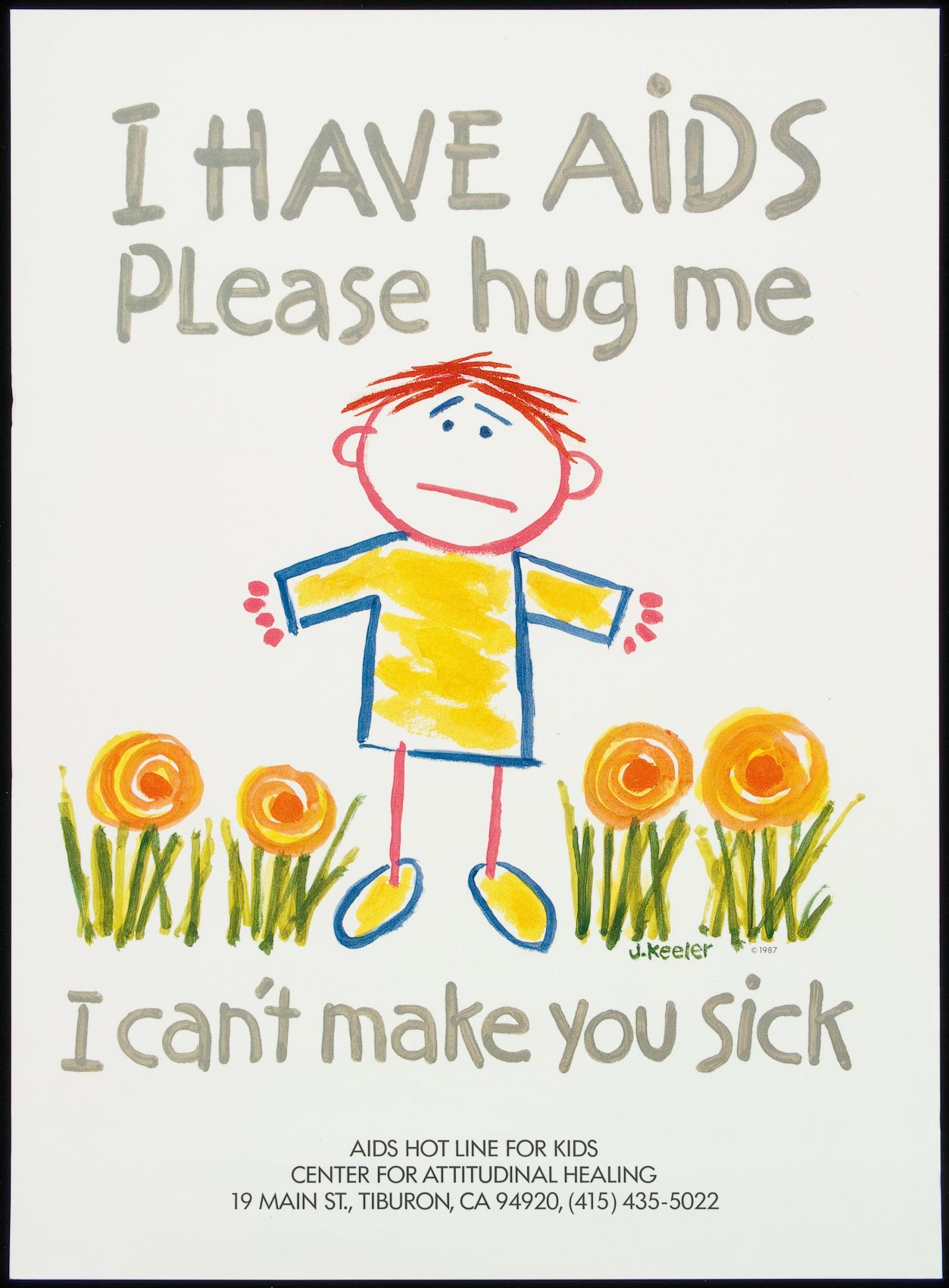

How so?There was a kind of fear and loathing of people with AIDS. There was hysteria. There was talk of quarantine. People wouldn’t touch people with AIDS. Nurses in hospitals wouldn’t attend to people with AIDS. It was a crisis.

I’ve written about early TV portrayals of people with AIDS and how phobic they were. There’s a story that at one point [the advocacy group] Gay Men’s Health Crisis put forward a spokesperson for a TV appearance, a person who had AIDS, and a producer said no, that person doesn’t look sick enough. We want somebody who looks really sick. They wanted somebody who looked terrifying, somebody who had Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions all over a bloated face. And that’s what they got eventually. It was a courageous person who agreed to appear. But at the same time, had the TV producers chosen someone who looked like your brother or your father, it would have helped humanize AIDS. And I think that’s what we did as activists, in various ways. We provided different pictures of people with AIDS. And one of those pictures was people fighting for our own lives, standing up for ourselves, and not simply passively fading away and dying.

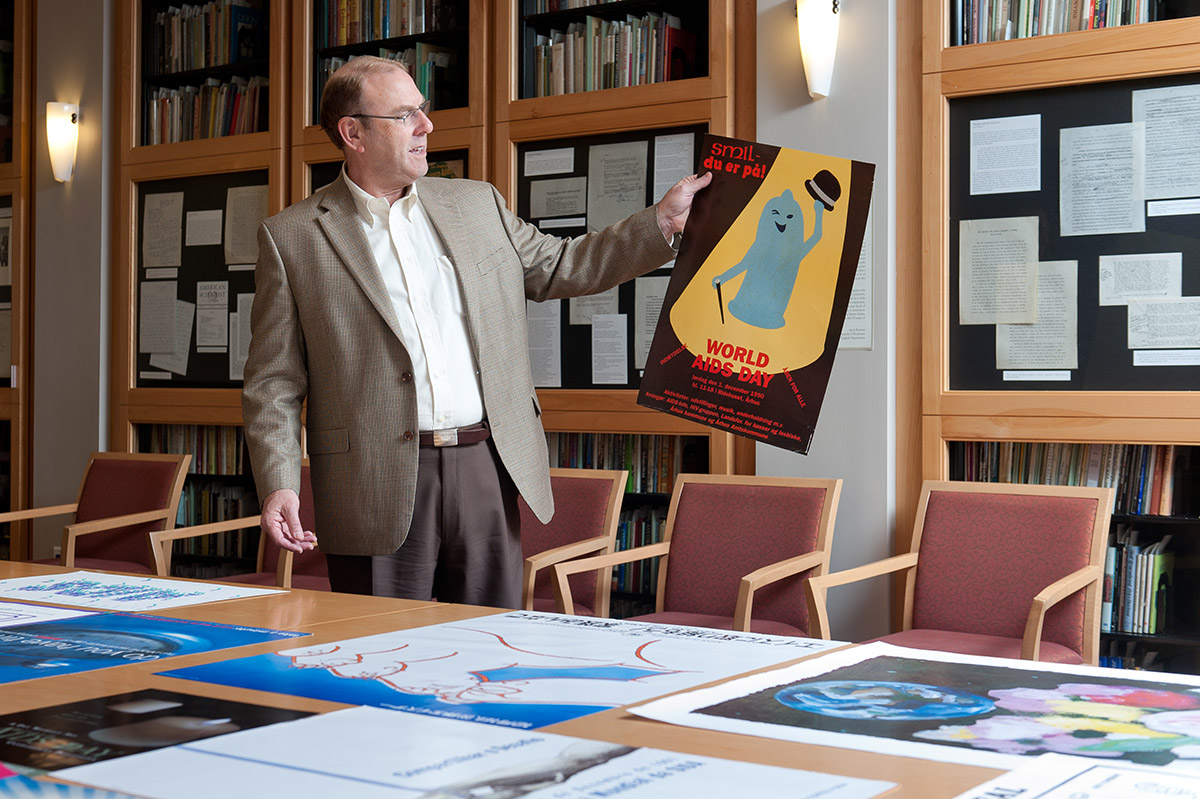

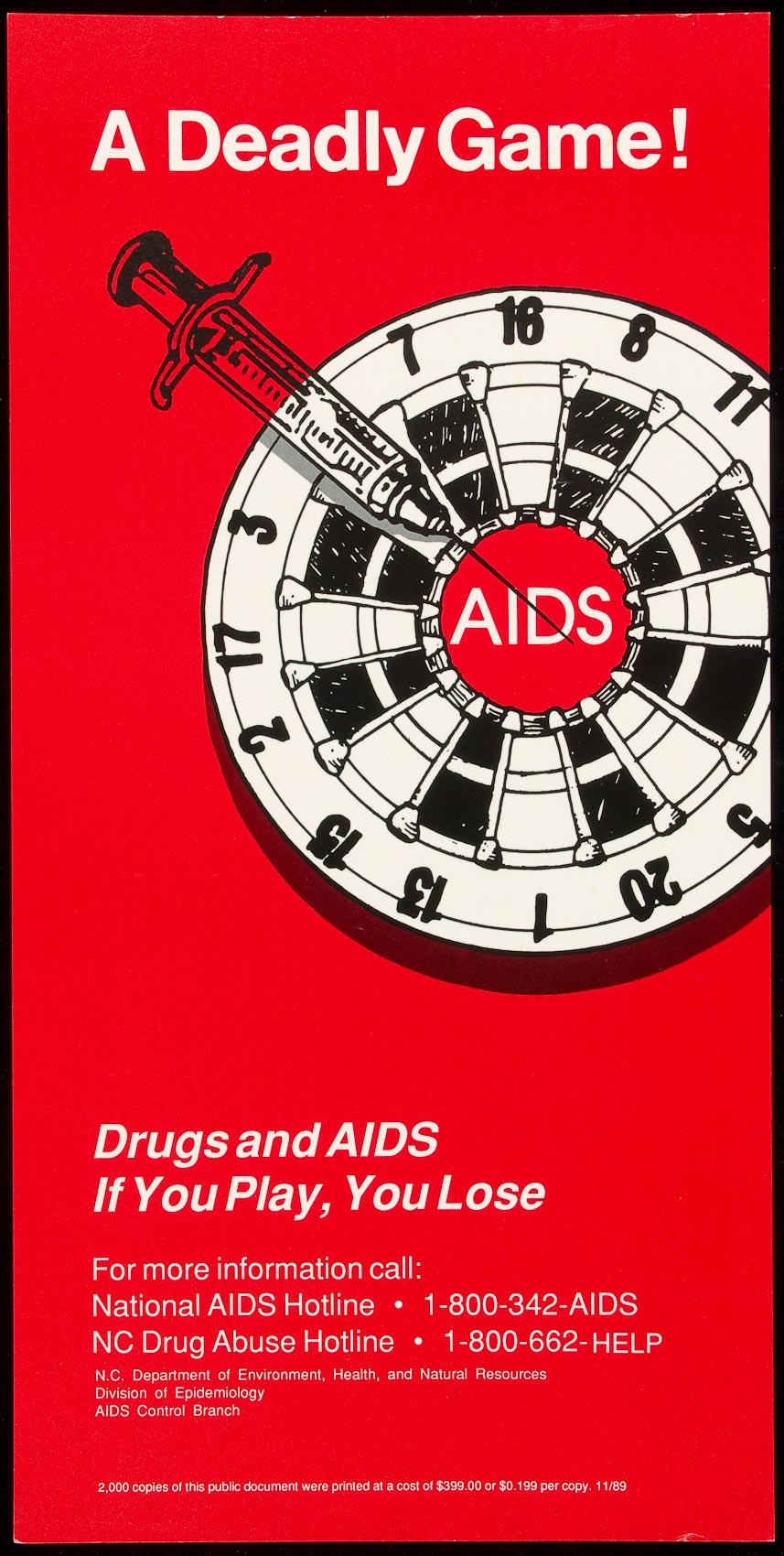

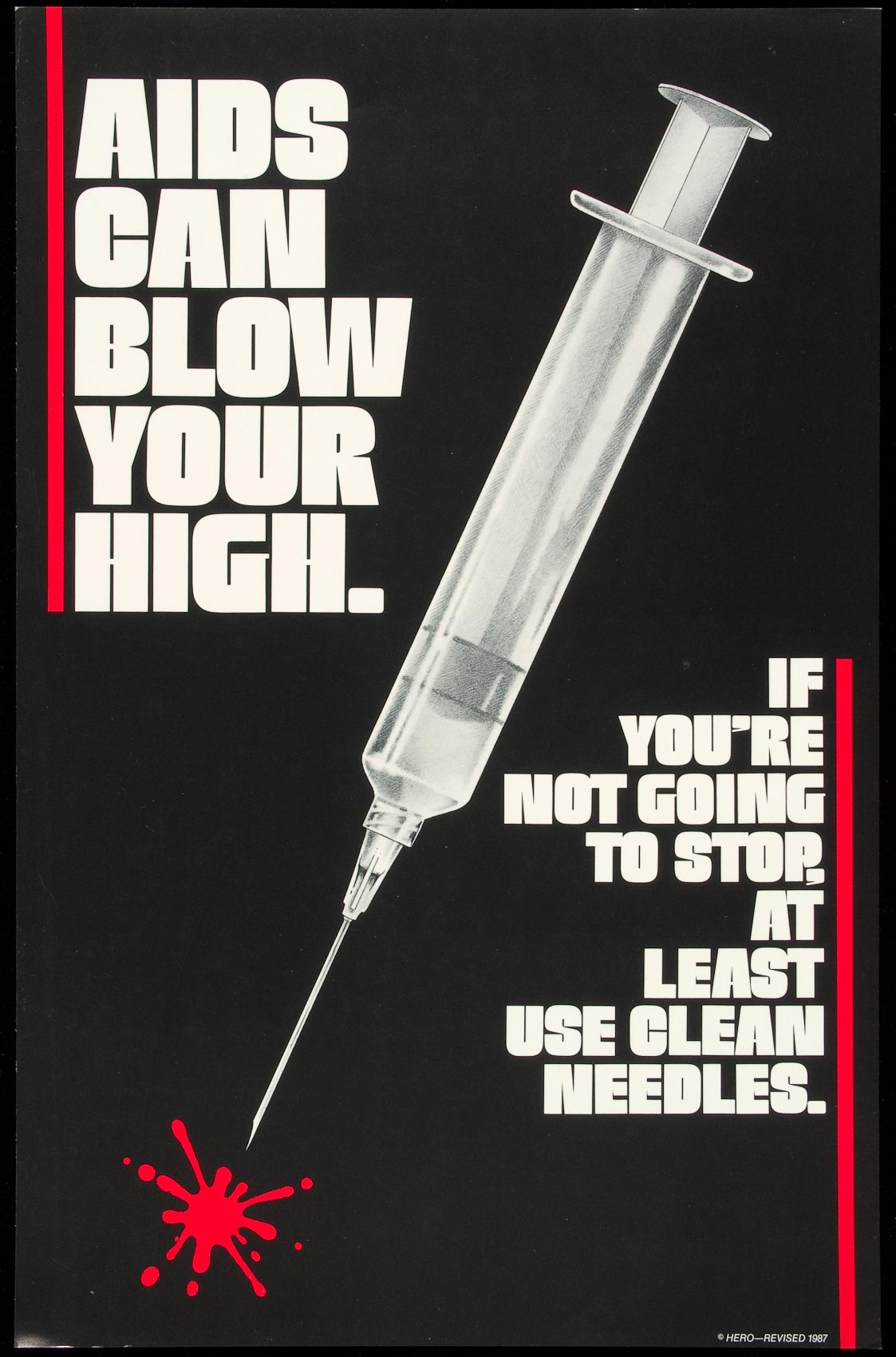

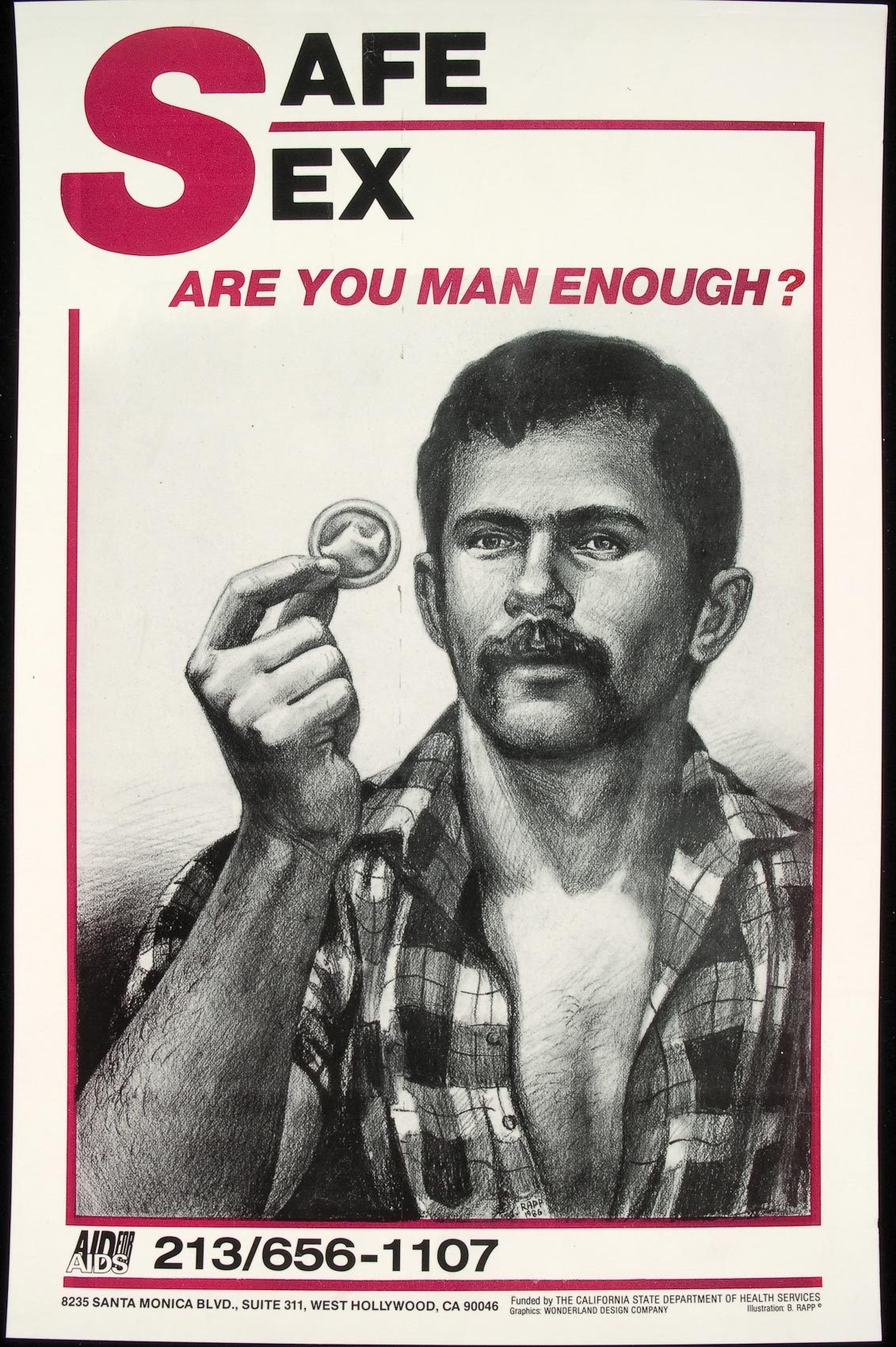

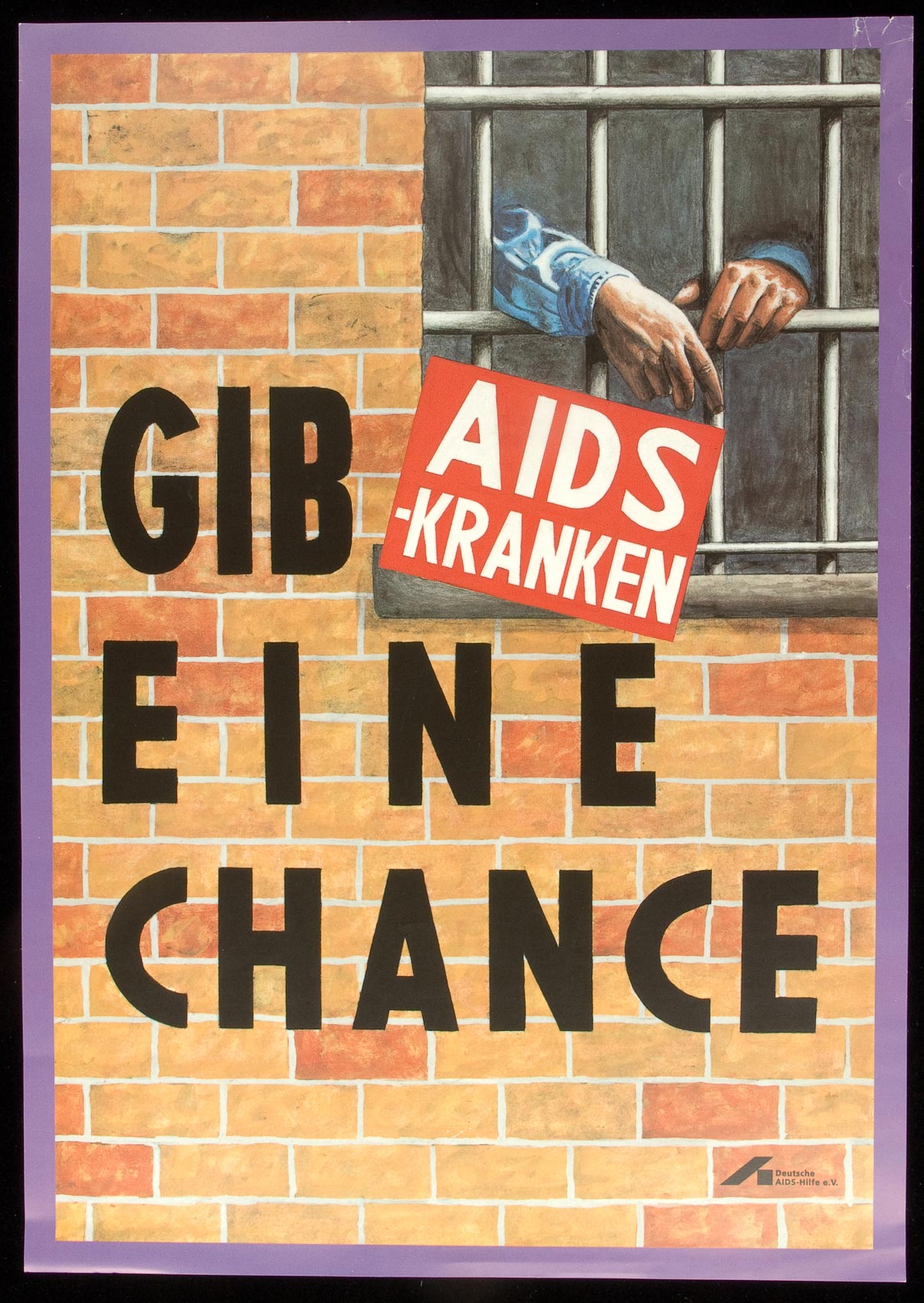

8,000 posters, one collection

For decades, Edward Atwater ’50, a professor emeritus of medicine at the Medical Center, has collected medical history artifacts. In 2007, he began turning his collection of more than 8,000 AIDS education posters over to the University.

From Time Magazine: “See the 1980s Posters That Helped Raise Awareness About AIDS” November 29, 2016

The AIDS Education Poster Collection, housed in the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation, is one of the world’s largest single collections of visual resources related to the disease. The posters date from the onset of the epidemic to the present, and come from more than 100 countries. The sample presented here represents only a small cross-section of the vast collection.

Douglas Crimp, the Fanny Knapp Allen Professor of Art History and a professor of visual and cultural studies, says that Atwater’s posters “represent an enormously wide range of approaches to [AIDS education] and to the populations that the posters were trying to reach.” But while the collection includes some posters produced by AIDS activist groups, governments produced most—and some governments he says, were constrained by attitudes like “sexual propriety,” and thus weren’t able to give clear information.

Crimp has written several influential books on culture and the AIDS crisis and was part of the organization AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT UP. He says that in the United States, effective public communication about the disease to communities disproportionately affected by it was often impeded by local health departments, and the federal government, who “didn’t want any so-called ‘positive representations’ of gay sexuality. Activists had to fill in the gaps, to the extent that we could.”

From the collection

You can browse the University’s online collection of more than 8,000 AIDS education posters at http://aep.lib.rochester.edu/

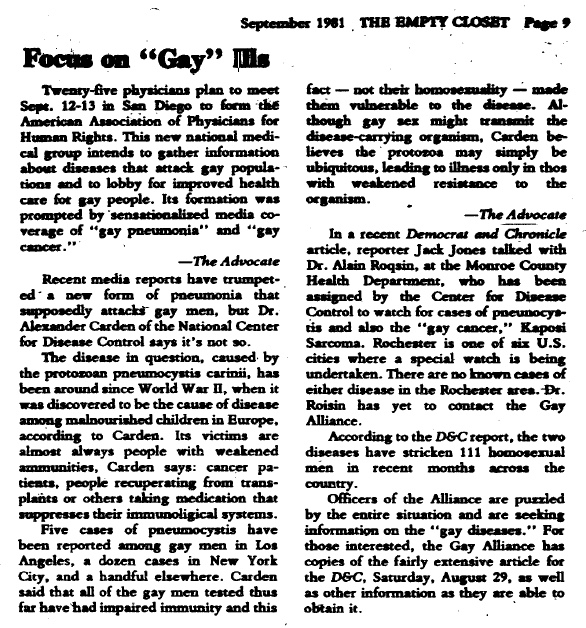

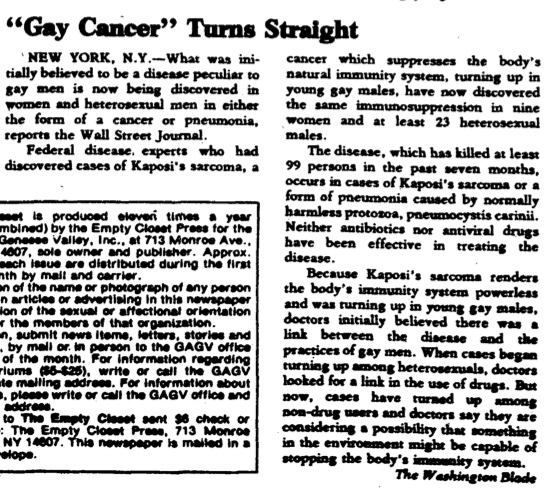

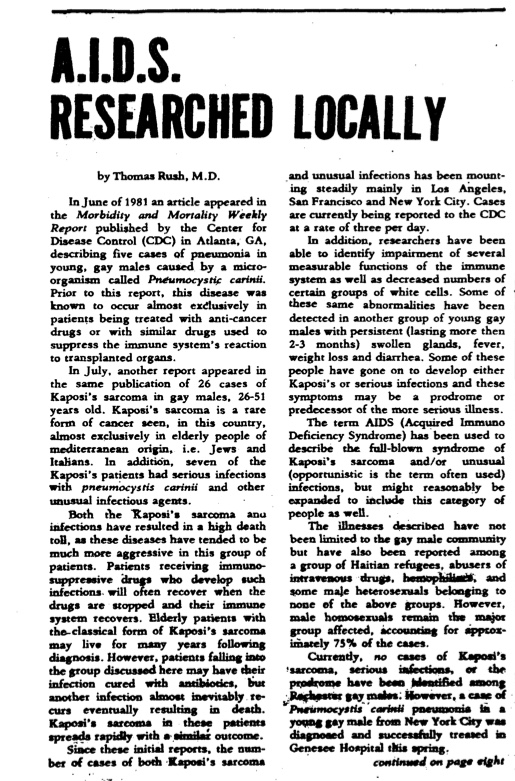

News from the front lines of the AIDS fight

Started by University of Rochester students, the Empty Closet is one of the oldest continuously published LGBT papers in the United States. Its pages reflect the story of the AIDS epidemic.

From the earliest days when a yet unknown and unidentified disease found its first victims in America’s gay communities, through the years of intense political and social activism for funding and research, to the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, and the news that basketball star Magic Johnson had contracted HIV, the Empty Closet chronicled it all.

The paper was begun at the University of Rochester by Bob Osborn and Larry Fine, the founders of the University student group, Rochester Gay Liberation Front, and later transferred to the Gay Alliance of the Genesee Valley (GAGV).

In 2010, the Empty Closet celebrated its 40th year of continuous publication. As it always has, the newspaper covers local, state, national and international news, as well as issues pertaining to the LGBT community.

For as long as it has been published, the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections has been collecting, preserving, and archiving the Empty Closet. It was from these copies that preservation microfilm of the journal was created. Funding for the microfilming was provided as part of a grant from the New York State Program for the Conservation and Preservation of Library Research Materials. The digitization of the microfilm was paid for by the Gay Alliance.

Current issues of the Empty Closet may be found here: http://www.gayalliance.org/emptycloset/

From the archives

You can browse the University’s online collection of the Empty Closet at http://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/EmptyCloset

Article does not explicitly mention AIDS, but references a “gay pneumonia” and a “gay cancer” that are being studied by the CDC.

Reports that 99 people have died in the last seven months, including heterosexuals and non-drug users.

In this front page story, the term AIDS is used in the paper for the first time.

Reports that there have now been nearly 1,000 cases of AIDS and 350 deaths, as the Gay Rights National Lobby works to secure federal research funding.

AIDS Task Force formed in Monroe County, with the goal of education high-risk groups, health professionals, and the general public.

Front page story reports on the CDC discovery of the virus that causes AIDS. In the article it’s called HTLV-3. “AIDS has killed 1,758 Americans since it first appeared in the United States three years ago.”

Front page story on the AIDS Memorial Quilt project in Washington.

First mention of Magic Johnson, who announced he was HIV positive on November 7, 1991. Most of the articles in this issue express frustration that the disease is now only being taken seriously and sensitively because a famous heterosexual individual contracted it.