This Longform Reprint is reprinted by permission of author.

The funniest thing I have ever seen (except for Bambi’s mother dying in the forest fire) was the David Susskind show called How to Be a Jewish Son, with Mel Brooks, David Steinberg, Goldberg from the pizzeria, and a couple of other guys who I don’t remember because Brooks monopolized the show. He went crazy talking, yelling, mugging—absolutely out of control. After 30 years of comedy—Brooks started in the beet soup belt as a tummler at age 14—all this gas, all this funny heartburn that had lived “like a knish next to [his] heart” was coming out in a series of wild comedic burps and farts. It was low, lewd, guttural, Yiddish-sprinkled humor, concentrated like a Binaca blast and funnier than his movies.

At this point Mel Brooks is sort of the godfresser of Jewish consciousness-Cinemazel. Woody Allen is better, but he’s too young. Melville, you should know, sits apart. At Factors’ Deli in Beverly Hills, where he rolls up in his smartypants little Cadillac Seville, Brooks is still the Show of Shows.

Somebody in Commentary can write an essay on the Selling of American Jewish Culture or Payess You Go. But Mel, like the godfather, has brought us his son, Gene Wilder, a mensch.

In Quackser Fortune Has a Cousin in the Bronx, he was an Irish manure peddler who is picked up by Margot Kidder, a rich American studying in Dublin. In The Producers, he was Leopold Bloom, the small-time accountant who gets cold feet in the middle of an improbable crime. In Blazing Saddles, he was the Waco Kid, a drunken washed-up gunfighter who comes out on top despite himself, in the film’s fantastic climax. In Woody Allen’s Everything You Always Wanted to Know… etc, he was the doctor who lost his home and practice for an affair with a sheep, and ended up in the gutter, drinking Woolite.

Even when he writes his own role, as he did in Young Frankenstein, he plays a man overwhelmed not only by a monster, but by his fiancée. When not a shlemiel, he is at least down on his chips.

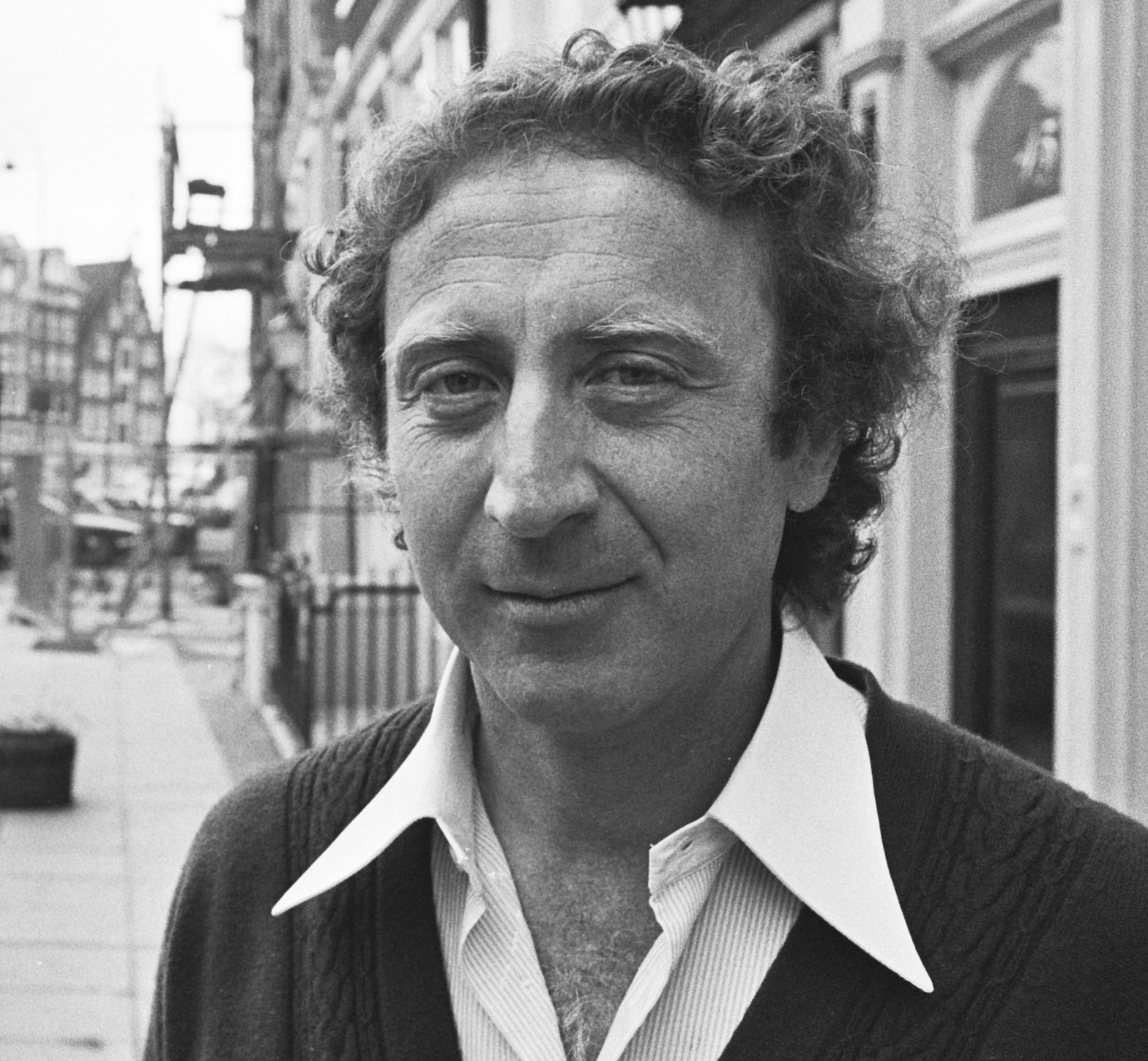

Friends said to me “Oh, Gene Wilder—he’s crazy, isn’t he?” No, he’s more the successful Jewish son, the nice young man with character and prospects. He’s almost sane.

“I’ve been married twice to Catholic girls. That’s a perfectly Jewish thing to do. But I’m really still insecure. Analysis has helped, but actors are all exhibitionists. My analyst said ‘it’s better than running naked through Central Park,’ and he’s right. In some ways fame is gratifying, but you have to be very careful of what you wish for because you just might get it.”

At 39 and looking younger, Wilder’s in the throes of success and young enough to have fun with it. He’s a very hot property now, before the opening of The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’s Smarter Brother, his first shot at the hat trick: writer, director, star—“it’s enough to knock the shit out of ‘em.” He’s hot enough now so that he doesn’t have to flaunt it and happily, talented and nice enough not to need to.

Wilder drives a rented Chevrolet Camaro. He’s thinking of buying a BMW because it’s little. He’s also thinking of buying James Aubrey’s house in Benedict Canyon for $150,000. Although Aubrey has a walk-in closet that outdoes a well-stocked haberdashery, the house is really just a bungalow, especially compared to neighbors’ Alice Cooper and Elton John. Wilder liked the place because it’s small.

“I’ve always had the quiet belief that my dreams will never come true—professional, marital, sexual. I’m divorced now, but now at least I know what it’s like to live with a real woman.” He said it very softly.

He used to be a fatty, but now girls in the script room at Twentieth Century-Fox have his picture up next to Paul Newman’s. Wilder on screen and in person evinces lovability; boyish softness and tenderness. He gets letters from women who want to mother him. But more from girls who see a tender father, brother, son, and lover figure. In real life, he’s Mister Lovable, too, but underneath you get the feeling that he, like Brooks, is one tough son of a bitch.

In Smarter Brother there is a real madcap idiocy going on between Dom DeLuise, Leo McKern, Marty Feldman, and the others. Even in a hilarious dual on the top of two horse-drawn coaches, Wilder—Errol Flynn—retains a certain suave integrity, a distance. In his scenes with Madeline Kahn, a music hall singer, his eyes stay unmoving and cold. It’s a bit like Keaton as described by Agee, where everything revolves madly around one fixed point, but it’s more coldly sexual.

There’s a great line in the film where Wilder, trying to get his hands on a secret document which controls the fate of England, straddles Madeline Kahn and fondles, not manipulates, her left tit, saying “You’re a frightened little girl who has to be sexually stimulated before she’ll trust anyone.

I wonder if it comes through on screen, that there’s something toughly sexual about Wilder.

“I like to do bizarre comedy realistically. I like to have the audience aware of what the characters are unaware of. I’m trying to walk a tightrope between comedy and, not tragedy, really, but I’m a romantic and that’s so often sad. I get letters from a lot of lonely girls who think that I would understand them. I was followed for a week by a girl in a little yellow Pinto. I had a conversation with Mel and decided what to do. She pulled up beside me at a traffic light and I stopped and got out of my car and walked up to her window. She said, ‘I don’t believe it,’ and I said (assuming his fatherly voice) ‘Let’s just say hello, let’s not be crazy in life, don’t go off in another world, let’s stay in this.’ The next time I heard from her she called from jail in Utah. She said I was the only one that she could call.

“Mel said to me once, ‘Gene, I’ve been thinking about you. You’re a romantic, you should wake up everyday for the next three or four years thinking today you’re going to fall in love. But whatever you do, don’t get married.’”

If Mel hadn’t gotten married, Wilder would never have met him. He was appearing on Broadway, in Mother Courage, with Anne Bancroft. Mel would come to pick her up every night. Eventually, he got to see the play, and almost immediately, he offered Wilder a role in the still-to-be bankrolled The Producers.

Wilder’s not overly defensive about Brooks’s influence—he readily acknowledges it—but he takes pains to point out the differences. Smarter Brother makes a few things very clear. Wilder is subtler than Brooks, sadder, more fully an actor—a comic actor—rather than a comedian. In person, he doesn’t feed you one-liners. He’s not compulsive like Brooks, although the hysteria that’s been so major a part of his perosna comes from some very real side of him. But he is a trained actor and he’s quietly intense and craft-oriented. He studied at the University of Iowa Theatre Lab and at the Old Vic, and later, with Uta Hagen and Lee Strasberg. His stage credits include Arnold Wesker’s Roots and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. He received a Best Supporting Actor nomination from the New York Drama Critics for his performance as Billy, the boy who stutters until he gets laid.

On screen, Wilder’s comedy has always been affecting because of the undertone of vulnerability and sadness which he projects. He tells of a real closeness to comedy that leaves people with a catch in their throats, but he always seems to be acting in a fantasy, with apprehension, understanding that it all may be suddenly jerked away.

Wilder’s comedy is a very concerned comedy. It’s endearing and more true to life than slapstick.

And, of course, there’s the face. Wilder has a great face, and, better than that, he has a great lovable face. He’s in the enviable position of being very much himself and getting highly paid for it. So what if he’s not a doctor or a lawyer. He’s okay if he stays away from sheep.

Jerry Leichtling is the author of Peggy Sue Got Married and Blue Sky. This article was reprinted by his permission.