A continued introduction to the life & times of Naismith Mandeville

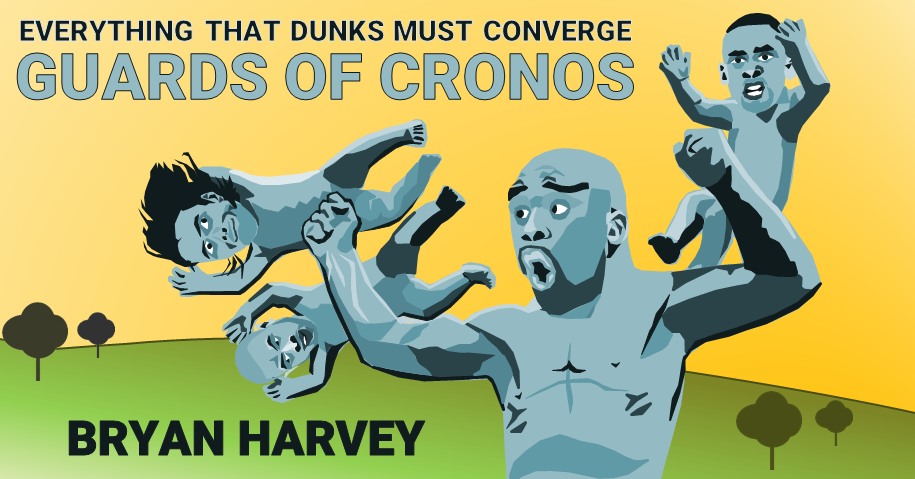

(Art by Todd Whitehead)

II.

[Continued from Act One: The 5th Sun]

Anfernee “Penny” Hardaway sat exactly on the couch where I had been sitting prior to answering his knock at the door. He wore a ‘90s Orlando Magic warm-up jacket and a pair of plain black basketball shorts. Rainwater dripped from his skin and soaked into the couch. Not really sure what to do next, I sat on the couch next to him. In the silence between us, we watched a late regular season game between the Bucks and Bulls. Giannis was on his way to scoring 32 points while running the point in what would become a 102 to 98 Milwaukee loss to Chicago.

The silence stretched on, becoming more and more noticeable, and part of me started to regret that this Penny had not been accompanied by Lil’ Penny.

“Do you miss it?” I asked.

“Miss what?”

“The game.”

“Sometimes.”

One of the announcer’s attempted to contextualize the seven-foot frame of Giannis playing point guard. He name dropped everyone from Magic Johnson to LeBron James, including Scottie Pippen, Jason Kidd, Boris Diaw (whose t-shirt jersey I was wearing), and even Shaun Livingston. He did not mention Penny, which made me feel sad for the guy sitting next to me. I told him, “I would have included your name.”

“What’s that?”

“I would include your name in a history of the position’s evolution.”

He nodded his head and emitted a low hum.

“You were awesome before the–” I cut myself off. What did he need me telling him any of this for? He knew he was awesome before the injuries. After all, Chris Rock, in his prime, narrated the point guard’s commercials.

He unzipped his Orlando warm-up jacket. He reached his hand into the chest pocket, posing for a second like Napoleon. A part of me wondered, Am I about to be shot in my own apartment by Penny Hardaway? The idea was ludicrous, but sanity in communication can disappear when all you have are silent gestures open to interpretation and guesswork.

Penny pulled his hand out of his jacket; it brought with it a hardback copy of Stephen Greenblatt’s Marvelous Possessions: The Wonder of the New World.

“I take it you’ve read this,” he said as he offered me the book.

I grabbed hold of its damp contents.

He stood and approached the television on the broken wooden crate. He eyed it from the side. “Your television’s old.”

He continued to study the electronic box before him, as if it were an artifact. I didn’t respond; I was already thumbing through the book’s contents.

“It’s not even a flat screen.”

“Um, yeah, it belonged to my parents. Think I watched the ‘95 Finals on it. You know, when Nick Anderson–” I stopped myself. Penny stared off into one of the room’s distant corners, like some elderly infant whose eyes were caught in the hypnotic spin of a displaced ceiling fan.

“Poor Nick,” he said, as if the man had died or lost a leg in Houston.

“Yeah,” I said. “Poor Nick.”

“Do you want to know who Naismith Mandeville is?”

“Um, sure,” I tried to hide my excitement. Of course, I wanted to know who Naismith Mandeville was, is, would be. Did Penny not see the stacks of the man’s manuscript, drafted, revised, redrafted, all around the room?

“Turn to any page in that book.”

“Okay.” I split the pages in half with my thumbnail and opened to one of the middle essays. The pages were absolutely coated in blue highlights. Annotations filled the margins.

“Go ahead. Read some of the comments, not the type mind you, but the handwritten comments.”

I started to read. They were all about basketball.

“Find anything strange about them?”

The annotations that weren’t about basketball were about ullamaliztli and then some random gibberish about a communion ritual involving jaguar blood.

“Turn to page two of the introduction.”

I did as I was told.

“Read that highlighted passage.”

And so I did, out loud. In blue was a paragraph that started:

“At a certain point I passed from the naive to what Schiller calls the sentimental–that is, I stopped reading books of marvels and began reading ethnographies and novels–but my childhood interests have survived in a passionate curiosity about other cultures and a fascination with tales.”

“Remind you of anyone?”

“Not really.”

“Keep reading then.”

“It will not escape anyone who reads this book that my chapters are constructed largely around anecdotes, what the French call petites histoires, as distinct from the gran rècit of totalizing, integrated, progressive history, a history that knows where it is going. As is appropriate for voyagers who thought they knew where they were going and ended up in a place whose existence they had never imagined, the discourse of travel in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance is rarely if ever interesting at the level of sustained narrative and teological design, but gripping at the level of anecdote.”

I stopped.

“What about now?”

“I’m really not sure what I’m supposed to be seeing here.”

“Didn’t you write in one of your letters that the motivational tactics of Phil Jackson struck you as similar to the anecdotal stylings of Mandeville’s stories.”

“Yeah, I probably said something to that extent. After all, the Zen Master holds ‘a passionate curiosity about other cultures and a fascination with tales.’” I read the line directly from the Greenblatt book as if it were my own. Then I started flipping the pages back and forth out of frustration: ”But I’m still not seeing whatever it is in here I’m supposed to be seeing.”

“Dammit, man, look in the back of the book!”

Feeling an immense amount of pressure to decipher some strange and invisible logic, I turned to the back of the book, where I saw one of those old manila library envelopes. In the manila pocket sat a checkout card with rows and columns. The rows were for a librarian to fill out. The columns bore the following headings: Date due, Borrower’s name, Date returned.

With the excitement of a middle school student giving a memorized report, Penny recited the following:

“I should, at this juncture, probably mention that my copy of Greenblatt’s book is a used one. It came chalk full of blue highlights and annotations. I ordered it online from the University of Chicago library system. Other than the annotations, the book arrived in fairly good condition, so I can only assume that the annotations are the reason it was pulled out of circulation. And of course, none of this would matter either, except that the last Borrower’s Name is P. Jackson. And the checkout date is September 1991, and it was not returned to the University library until July 1993.”

“P as in Phil? Are you saying Phil Jackson is Naismith Mandeville?”

“No, that’s not what I’m saying.”

“Then, what are you saying?”

“I’m saying I think you should come with us.”

“But there’s only one of you.”

A second knock sounded at the door.

Penny gestured at the door: “If you don’t mind . . . .”

I walked over and opened it. A silhouette in a long coat and a fedora loomed large in the door frame. “Mr. Harvey,” he said, as he passed over the threshold, and I immediately recognized that lanky sleepiness and hint of a lazy eye.

Tracy McGrady continued, “Grab whatever you need–we’re headed out the door.”

“Great,” I said, “but I still have no idea who Naismith Mandeville is.”

*****

Penny Hardaway and Mr. McGrady (I was instructed to address him in a formal manner, as opposed to T-Mac) escorted me into a chik Art Deco study. The walls and shelves and furniture were all flawlessly white. I felt like a kid in his grandmother’s living room–I felt afraid to touch anything. Through the closed double-doors, I could hear the light conversational jazz and clinking of fine china that suggest a rather stuffy and boring party going on in the adjacent room.

Since the discussion about Greenblatt’s book had come and gone, Penny had said very little, and Mr. McGrady had said even less. I sat on the couch for a while. Time passed, at least an hour. I started strolling around the room, eyeing the various artifacts and rare sculptures adorning the walls and shelves. I held my hands behind my back, my right fingers clasped around my left wrist. I was afraid of knocking anything over, of disturbing the order of this universe.

My back was to the double-doors. I pivoted around when I heard the jazz piano keys grow louder. Either T-Mac or Penny said, “That Deron Williams sure can play, can’t he?” To which the one who hadn’t spoken said, “It’s a shame every riff has to end.” A man wearing a tuxedo entered the room. He closed the white doors behind him with little effort, and, in a way, they resembled a swan’s mighty, yet graceful wings folding after a long and arduous flight. I thought about Zeus. I thought about Leda. I regretted having ever left my apartment.

I wished I’d been wearing a fedora.

“I trust your trip down was comfortable, Mr. Harvey.” I could hear the clasping of the lock on the doors. “My men didn’t alarm you, I hope.”

He approached me with his hand extended. “My name is Hill–Grant Hill.”

“I know who you are, Mr. Hill, your years with the Pistons were awesome, absolutely awesome!” I sounded as giddy as my middle school self felt watching Grant Hill turn into a triple-double machine alongside Joe Dumars and whatever else was left in the ruins of old Detroit.

“What do you think of your surroundings? Did my associates offer you anything?”

I looked at Penny and T-Mac. One of them shrugged. The other did not acknowledge me. “They didn’t.”

“Well, what would you like?”

“I don’t know. A beer or a water’s fine.”

“Well, which one is it?”

“A beer–I’ll take a beer.”

“I think moving forward it’s better if you act more decisively.”

I aimed to change the subject: “You have some nice pieces here.”

“That we do. In my many rehab stints, .”

“Yeah, I definitely noticed.” I wanted to ask about Naismith Mandeville. Part of me wondered if what I had come to assume was a pseudonym belonged to Grant Hill. I also wanted to play it cool; I was in a room with three of the greatest perimeter players never to win an NBA championship. And, sadly, this also made them appear at home among the cracked and broken vases and bowls and urns from various places around the globe that had somehow found their way into this immaculately white room.

“Have a look over here, Bryan. Do you mind if I call you Bryan?”

I followed Grant Hill over to what appeared to be a glass coffee table, its legs cut from some unidentified stone. He pressed a button on the corner of the table. A panel in the floor slid open in the same way that a sunroof on a car might, and I noticed that between each stone leg of the table stood a glass wall. In truth, it wasn’t really a coffee table, but a glass cube. As the panel opened full, a platform rose from the dark antechamber below and, stretched across its surface, was a document of historical importance.

As it rose, a beaming Grant Hill said: “This might interest you.”

“Well,” I said. “It looks important. It’s old. I can tell that. Probably from the sixteenth century. Is it part of the Codex? Yes, it resembles the fifth codex, I believe.”

“It’s actually a copy of James Naismith’s official rules of basket ball. As you may recall,

I did remember something to that extent, but I also recalled another detail which called into question the claims of Mr. Hill. “Didn’t a group of Kansas Jayhawk alum bid on it. If this is the real thing, shouldn’t it be in Lawrence, Kansas.”

“Trust me, Bryan, if you were to visit Allen Fieldhouse, you would find almost an exact replica of this document, but it would be just that–a replica.”

I bent down towards the glass cube for a closer look.

“We switched them just before the auction.”

“We?”

“Why the men in this room, and a few others not in this room. We are, after all, a League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.”

“I think that name’s already taken.”

“Nothing. It’s just that you’re referencing the wrong Sean Connery film, that’s all.”

“I’m an art and history buff, Mr. Harvey. I do not go in for fluff.”

“Why did you switch them?”

“We needed the original.” He hit another button that changed the color of the glass cube from transparent to ruby. “We had reason to believe that a secret inscription was on the back of Naismith’s Rules.”

“Okay, now you’re not even dealing with Connery films.”

“This is not a movie, Mr. Harvey.”

“Then what is it?”

He stepped away from the cube, moving with hints of grace towards the bar. “Can you make out the secret inscription?” I heard the snap and release of a bottle cap. “It’s faint, but it’s there.”

I leaned in and, admittedly, I did have to squint in order to read it. I read it once to myself and then out loud:

Whoever hunts and kills the one true jaguar and drinks its blood will rise like a feathered serpent towards the outer rim of his salvation.

I looked at Mr. Hill. “This is nonsense, right? It’s gibberish.”

“Is it?” asked Penny.

“Okay, I’ll give you this: it’s coincidental gibberish that on one side you have Naismith’s rules, which read like the Ten Commandments of basketball–”

“Which,” Mr. Hill cut me off, “imply a certain rigidity to the game; a certain exactitude in its fixed and unchangeable nature.”

“Yeah.”

“Do you want that beer, Mr. Harvey?” He extended an open bottle to me. “Or, would you like to try something else?” He extended a bottle full of a deep red liquid in it.

“Is this my red pill-blue pill moment?”

“It’s important you be precise here. We already have our doubts that you’re the right man for this job.”

“What job?”

“The publishing of Naismith Mandeville’s works.”

“I still don’t know who Naismith Mandeville is!”

He ignored my anxiety: “Which will it be?”

The bottle of beer and the dark red liquid hovered before me. I grabbed the latter. I looked for a tell in Mr. Hill’s face, but there wasn’t one. I raised the bottle to my lips. I tipped it so the contents flowed over my tongue. I swallowed.

“It tastes like Gatorade,” I said.

“That’s what I thought,” said T-Mac.

“Wanna be like Mike?” asked Penny.

And Grant Hill added in a cool, clean manner, “You chose wisely, Mr. Harvey.”

Then he handed me the beer. “You still might want to wash your mouth out with this–you just swallowed jaguar blood.”

I took hold of the beer bottle: “I still don’t get what the hell is going on.”

“How’s your travel schedule looking?” Mr. Hill asked.

“Um, I teach on Monday.”

“Maybe call in for a sub.”

“Why?”

“We’re traveling to Houston.”

I laughed.

“What is it?”

“Nothing. I just thought if we went anywhere it would be Orlando.” I could feel all three gentlemen cringe at the naming of that cursed city in the swamps of Florida. “My bad, guys,” I said.

Needless to say, when we stopped by my apartment later that night, it had already been ransacked.

Table of contents

(Art by Todd Whitehead)

Act 2: Guards of Cronos

Shaq, the Bounty Hunter

Udonis Haslem, Help in midst of the housing crisis

Songs of Jameson, shots of Jamison

Melo, New in town

Dwyane Wade’s opening credits

AI, Walking in Memphis

Linsanity & the sounds of the city

Kevin Durant & Russell Westbrook, Young Guns

Kawhi & the typewriters

Deron Williams, Dive bars & sad musicians

LeBron and Shaquille, the front porch around midnight

#BallIsStillLife

Shaq, the Bounty Hunter

“Kobe, tell me how my ass tastes.” —Shaq

He loomed on the street corner like a great, urban Sasquatch watching the door of the red brick butcher shop. He was waiting for the last customer to walk out. Then he would go inside and get the answers he was looking for. In the meantime, he gritted his teeth and sucked in his gut, trying to look every bit as imposing as he had in his youth. In his hand, under his long, black pea coat, he held the wooden shaft of a sledgehammer, its head all notched and dinged so that the black paint gave way to a silver core. Every so often, he lifted the tool and then loosened his grip on it so that it would slide back to the earth, the metal ring of its landing floating up all seven feet from the curb to his eardrum.

The sun was setting, and a woman walked out of the shop with a brown bag in her arms. The wooden door, with its glass panes, shut, and the man with the hammer could see the sign on the door flip over from OPEN to CLOSED. So he walked with silence as his only companion down the sidewalk. When he got to the door, he tried the knob, but it was locked, so he tapped on the glass with his bare knuckle. A much shorter man came and unlocked the door, cracking it open just enough to poke his smiling lips and beady eyes out into the street.

“Uh, sorry, sir, we’re um closed for the day, but we can take care of you tomorrow. Whatever it is.”

“I just wanna speak to the man who runs the place. That’s all.”

“Well, he don’t like to be bothered. ‘Specially after closing.”

“It’ll be a quick talk. Just a brief Q and A.” He grinned, wide and scary.

“Uh, I don’t know. Hakeem really don’t like no one botherin’ him.”

“Is that his name—Hakeem?” The man’s grin became a smile. “Hakeem! You in there? I just wanna talk. Just one question.” He moved towards the door.

“I think you better go, sir.”

“I think you better let me in.”

The smaller man tried to shut the door, but the head of the hammer stopped it. The large man bulled his way through the doorway, tossing the smaller man aside like a traffic cone.

“Hakeem! You in here? ‘Cause I know I am. I’m standin’ right here in the middle of your fuckin’ shop.”

Hakeem, with streaks of gray in his hair, came out of the back room, washing his hands, and stood behind the counter. “You are a very loud man. Or, perhaps, just a very large boy.”

They stared at each other, neither one saying a word. Hakeem untied his apron and folded it neatly on the counter, careful not to touch the blood stains. “Kenny, are you alright?”

The large man in the center of the shop answered, “He’s fine. I barely shoved him.”

“I didn’t ask you.” Hakeem turned towards Kenny, who was still on the floor.

“Yeah, I’m alright,” said Kenny as he got up.

“Then you can go home.”

“Are you sure, Hakeem?” Kenny was eyeing the hammer that the large man was making no effort in hiding, in fact he was making an effort to display it.

“Yes, Kenny, I’m sure,” said Hakeem. “Besides, this man just wants to talk.”

“I’ll be at the bus stop,” said Kenny as he walked out. He paused and pointed, “Just down the street.”

When the door shut, the two men continued the staring contest.

“Do you want me to make you something?” asked Hakeem.

“I don’t want anything, and ” Shaq grimaced at the stacks of raw meat.

Hakeem said nothing. A resolute calm emanated from him as if the world were nothing more than a dream he could wake up from at any moment.

“I want you to tell me where I can find Kobe.”

“And who is Kobe?”

“Look, I’m not here to play games,” boiled the man. “I know he used to come here as a kid. I didn’t come here by accident. I’ve never gone anywhere by accident. I’m a vengeful motherfucker, and I didn’t come here by accident.”

“I vaguely remember the boy, but I haven’t seen him in a long, long time. Maybe you should try somewhere else.” Hakeem turned away from the man and headed for the back room again. “Maybe you should try somewhere with less patience.” As Hakeem put his hand on the door’s brass plate and pushed forward, the sound of crashing glass shattered the room, and he could feel slivers raining on the back of his neck. And in the reflection of the door’s small, square window, he could see the large man smashing up his counter and display case, full of raw steaks, pork chops, and other meats, with a sledge hammer.

“Do I have your attention yet? ‘Cause I will fuck your patience every minute that you make me wait.” The large man, with a head like a boulder, gritted his teeth. “Where’s Kobe?!”

“He’s gone west, and as I said, I haven’t seen him for quite some time,” said Hakeem, still facing the door to the back room. “But last time I saw him, he was slaughtering a chicken that my employees all called Mr. O’Neal. And it wasn’t by accident. I could have killed it, but I left it for him and another boy. Kobe took its life. Didn’t even hesitate.” He took a breath. “Isn’t your last name O’Neal, Mr. O’Neal?”

The head of the hammer clanked against the concrete floor, chipping it.

“Maybe you should ask yourself, Mr. O’Neal, why am I chasing after something that all signs suggest is destined to kill me? You are not a wise man, Mr. O’Neal. Not wise at all.” Hakeem walked into the back room, leaving the door to swing in Mr. O’Neal’s loneliness.

The man pleaded with the sage who was no longer in the room, “Tell me where he is!” You could hear the pain cracking in his voice. “Tell me! Hakeem! Please!” Shadows moved through the shop, but Hakeem did not answer. Mr. O’Neal heaved the hammer over his shoulder and walked out the front door and around the corner of the small brick building, opposite the direction he had come. As he walked down the dark street, he could hear chickens rustling and cooing from their coops; and he wanted to smash their beaks with the metal of his hammer; but he didn’t have the heart to do it. He hurried his pace, crying in the night air, hoping no one would notice him. Behind him dragged his hammer like the tail of a child’s blanket.

When he got to the parking lot, he climbed into his diesel truck, threw the hammer behind the driver’s seat, and sat peering into the black hole that had opened up in front of him. He wanted to hunt down and kill Kobe, the man responsible for him sending him to prison, and until now, that’s what he thought would happen if he ever encountered his partner in crime again, but Hakeem’s comments had stripped him of his certainty, exposing the steel of his being to rust and ruin. Shaquille O’Neal turned the key in the ignition and peeled out of the parking lot.

As he drove down Main Street, he heard a whistling sound from above. He looked up and saw what looked like the fuselage of a space ship, on fire, falling out of the sky. It grew larger and larger, spewing great orange flames. He swerved to avoid it and felt the truck strike something soft as mud instead. He slammed on the brakes, rolled down the window, and leaned out into the smoke and ash filled air. A body was groaning in the street, coughing and gurgling in its own blood. Shaquille O’Neal slammed on the gas and got out of town, leaving the body to fend for itself next to a burning hunk of heaven, that, for all Shaq knew, was hurtled by God Himself. The debris burned like a hot coal in the heart of the city, flickering next to a man who in his unconscious state believed the world was ending.

Udonis Haslem, Help in midst of the housing crisis

Udonis sawed through the lock on the gate. “Easy,” he said as he and his partner trespassed into the backyard. They were there to steal the air conditioning unit and the pool pump. He’d been doing this sort of work for a while. His boss’ secretary would call him up and tell him where he could find a list of addresses. He would find the list of addresses and, sitting in a mall food court, mark the addresses with tiny red x’s on a map. Then he would head out in his pickup truck.

When he first started, he rode in the bed of the truck. A guy named Eddie or Lamar would man the wheel. The other would ride shotgun. In the back with Udonis was a young guy from out of Chicago or Milwaukee. Udonis never could remember and didn’t much care to ask. The boss at the time’s boss had brought him in special. Udonis was just a kid from Gainesville, who had ended up by chance in Miami as opposed to anywhere else.

Back then, most of the houses they picked over belonged to people who really couldn’t make ends meet. There were less pool pumps in those days, unless a house happened to be the former property of an online mogul who’d gone bust with the dot com bubble. Then work slowed and Udonis turned to doing real work (read that: legitimate work), but now, now every other house was all a hermit’s shell and no crab.

And Udonis could barely keep up with the surplus of other people’s bad fortunes.

“Oh! Shit!” Udonis dropped his flashlight on the white lawn pebbles edging the backyard. The light blinked upon contact with the ground, but then the white column illuminated the onyx colored eyes of a massive alligator. Its eyelid blinked away the moment, and the creature sat in stony admiration of all antiquity staring back at it.

Udonis took out his phone. “Um, yeah, we got ourselves a problem.” He listened to one of the office managers respond to his report.

“You’re not listening to me. I’m saying the damn thing is in the way. No, it’s not in the pool. It’s like right up on the pump.” He listened to the response.

“No, I’m saying the only way I’d fuck with it is if it were a mascot. There’s just some shit that ain’t worth it.” The gator groaned like some prehistoric garbage disposal. “Did you hear that?” Udonis held the phone out towards the gator.

And then came the splash.

Udonis dropped the phone next to the flashlight. The voice on the other end called out for him, but he was already sprinting for the pool. Thrashing in the water was the man the office had wanted him to introduce with the process. In the margins of the flashlight’s beacon, he could make out an arm here and a leg there. Most of what he saw, though, was dark and scaly and wet in the moonlight. He dove in. He engaged with the gator and its prey. If it had been light out, he would have seen all the blood in the water. But it wasn’t light out, so the water just felt wet.

When all was said and done, he sat on the edge of the pool with his feet dangling in the murk. The other man’s shirt was wrapped around the end of his arm. The man’s shirtless dead body lay next to him, and on the other side of that was the body of the second large reptile Udonis had witnessed that night. The first sat in the wavering light of the flashlight, chewing on Udonis’ cell phone.

“Easy,” he said, and shook his head in disbelief.

*****

The door of Mr. Wade’s office swung open and a gust of wind tore through the room. “You can leave, Mr. O’Neal. Leave now. Leave your clients. Whether they happen to be buying or selling, it doesn’t matter. You can leave your brief case too. In fact, leave all your belongings on the desk. We’ll have the authorities collect them. Use your two legs and walk to Phoenix for all I care. But your time in this office is done.”

“Are you kicking me out after all I’ve done for you?” bellowed Mr. O’Neal. “Do you even know how we came by this office? Do you have any idea how that slumlord Riley is able to do what he does?”

“I’m not having this talk.”

“Doesn’t matter if you have it or not. It’s what we are, brother. You can’t change that.”

“I’ll do whatever I fuckin’ please.”

The two stared mercilessly over the broken space.

“Mr. Haslem,” Wade called out his door and past the man attempting to eclipse the world beyond. “Mr. Haslem, call the police. Tell them we have an intruder who refuses to leave.”

“Udonis, you make that call, and you won’t be no Captain Hook, more like Edward fuckin’ Scissorhands. You feel me on that? Your boss is forgetting who I am, but you know, don’t you?”

Mr. Haslem did his best to thumb through the rolodex of the firm’s contacts. The sound of cards under his hand and hook fluttered like birds trapped inside a bag. The wings beat against the frustration of limited space. Stopped. And flapped again. Unable to find an opening. An exit. A chance to fly.

“I’m . . . I’m with D-Wade on this, sir.”

Mr. O’Neal offered up a mumbled repeating of Mr. Haslem’s response, but he appeared as much in parody of himself as he did the smaller man. However, he did not back away from the chance to offer up a grand finale to the end of this business relationship.

Mr. O’Neal lifted a chair above his head and tossed it at the foot of Mr. Haslem’s desk, causing a fake potted plant to topple from the desk. Then the man snatched a letter opener and lifted it high for the kill, but he had no beast to slay. The blade fell to the carpet, harmless as could be, and Mr. O’Neal blew through the office’s front door and out into the street.

Mr. Haslem couldn’t help but notice, that from inside the office, the sign on the door read: CLOSED. Then he turned and took in the results of the fizzled tsunami and said to his current boss, “At least nobody got hurt.”

“Shut up, Udonis, you lost your fucking arm.”

Mr. Haslem eyed the metal hook and shrugged.

“Now find a replacement or we’re both done here.” He paused and then added, “Someone who knows their role and is of sound thought and mind would be nice.”

“What about Marion?”

“No, Udonis. The Matrix failed us.”

“The other O’Neal.”

“No.”

“Beasley.”

“Are you even trying, man?”

“But if we’re in a business of shady dealings, how are we going to find someone who’s not, well, shady, sir?”

“We’re in real estate, Udonis, and it’s as straight forward as that.”

Udonis watched his boss from across the office’s wide berth. Sitting at his desk, Wade appeared to have rocky scales and pyramid teeth, and yet his silhouette was perfectly human.

Here was a reptile hatching inside a man’s ambition, thought Udonis.

Then a man named Mourning approached Wade from one side of the desk. He appeared to be swearing fealty to Wade as another man, who Udonis didn’t recognize, closed the door. And like a Mafia housewife, Udonis was left to fill in the missing pieces. He imagined the good at the end of the journey. He scratched an itch with his hook for a hand.

Songs of Jameson, shots of Jamison

(Image by Mike Langston)

“The writing’s on the wall. Whatever you say happened between the coaching staff, Kobe and Dwight—it was a combination of everything.”—Antawn Jamison

Backstage in Atlanta, Antawn Jamison could feel the caffeine percolating through his veins, trembling in his hands, the ones he knew not what to do with unless they were tickling the keys or holding a microphone. He watched the cigarette quiver like the leg of a bird between his long ebony fingers, the smoke graying the white moons of his nails, and he did not know if he could go on–he did not know if the music could still save him. He was old now, so much older than his thirty-something years. Bad booze, bad women, and too many bad–no, terrible–songs had damned him into this moment of trepidation, to sing or not to sing. He was a canary in a coal mine and he felt like dropping.

Instead, he let the husk of the cigarette slide out from his hand and into the grasp of gravity until it splashed into what was left of his coffee. Once upon a time, it would have landed in something with a bit more bite, at least a Jack and Coke, but now he just drank murky brown water that made him shit too much and kept him up at night. But, dear god, could the man still dream, or, in the least, pretend to do so.

In fact, he’d been chasing the same dream from Planes, Trains, and Automobiles his entire life. He’d gone from backwoods joints and dirt road churches in his Carolina youth to the Golden Gate, the Southwest, Chocolate City, and the Great Lakes. But, now days, when he took the stage, he’d reach for the microphone with one hand, while snapping to the beat with the other, his shoes doing their best James Brown shuffle, and the voice wouldn’t come. He’d stall, do a few more dance moves, but the voice was lost. He hadn’t been able to sing since his stint in Los Angeles, since he rolled over in the night and discovered the dreams were all nightmares, mutilated and terrible. And the coffee—the coffee was to keep him awake, to keep him away from the dream’s inevitable failure.

Antawn stared at the cigarette butt floating in what was left of his coffee. In some ways, the act was like staring at a turd in the bottom of a miniature toilet bowl. A shadow fell across him, and he looked up at the white skull of the club’s manager, Danny Ferry.

“I don’t know what that crap was in LA—and trust me it wasn’t just a difference in opinion—but if you can’t pull it together, then you can go ahead and leave.”

Antawn did not find the news surprising. By the door was his bag, not even unpacked from his arrival to what felt like the Chitlin Circuit. He put the styrofoam cup on the floor. His mind was not on Atlanta, not on whatever meager crowd had gathered at the Hawks’ Nest. Instead, he thought about a folk singer he’d last seen in Los Angeles and how she’d looked younger before she cut her hair. Immediately, he regretted thinking of her because as soon as he saw her tough Canadian face he knew the nightmare’s flames couldn’t be more than a few moments away, smoke rolling into his memory like thunderclouds in late summer.

“I’ll be going.” He wanted to be far away from everyone when the terrors started, when his tongue started to taste the last real drink he’d ever had, when all he could feel was the weight of the dead bodies. He stood up, walked the room, and grabbed his bag. In the alleyway, the stars appeared as they often do in a city’s sprawl, like phantom acolytes of worlds long gone. Antawn was no longer in the present. His body stood on Atlanta asphalt, but his mind moved through time.

*****

The bottle gulped as liquid and air swapped places. However, when Jamison turned the bottle right side up the almost human sound of an inanimate object chugging liquid echoed from behind the storeroom closet’s door.

“I must be losing my mind.” Antawn crept across the room, leaning awkwardly every few steps like a zombie a trying to balance the world on a skateboard. He opened the closet door.

Drink in one hand, he used the other to pull a string. A click followed, but no light. He stepped in to get a closer look at where the bulb should’ve been and glass crunched under his feet. And that’s when he saw it. Standing on broken glass, drool stringing from his lip, he saw a faint yellow line tracing the outline of a door in the closet’s back wall. Funny, he’d never noticed it before. Of course, he’d never been inside this closet before either. He reached to pull the curtain back and fell through, tumbling down a flight of hard stairs. When he landed at the bottom, he recognized the all too familiar symptoms of a concussion. Then he recognized two faces he hadn’t expected to see in the hidden basement of an L.A. bar.

The Busses—for all their billions—were bound and gagged to director’s chairs. Standing between the brother and sister—the children of empire—was Kobe Bryant, a man who until now had been mostly invisible to Antawn. But here he stood with a gas can in his hand and a shiny slick of fuel beneath his feet. Antawn remembered back to his days in the Cleveland clubs. There, he had met a large man with a trench coat and hammer. “They call him the Black Mamba, but I’m gonna make boots out of his skin,” the man had said of Bryant. Antawn looked at the man before him and thought, I don’t think anyone’s killing him anytime now or later. At this moment, Antawn realized later, it would have been appropriate to panic. Instead, he stood up and dusted himself off. Then he kept standing there with his lips puckered, as if he had come to kiss the devil himself. (And maybe he had.)

The Busses looked his way, crying to him with gagged mouths, jerking their chairs as much as they dared, eyes clawing in a lost effort at the air around them. Antawn could tell they were as good as dead. He could tell because the whole room stunk of gasoline.

“Mr. Bryant, they gonna have a hard time signing any paychecks all tied up and such. What you thinking of doing?”

“You hear that, you dumb fucks, even a washed up soul singer recognizes things ‘round here are about to change.” Kobe swung the gas can up over his head, moving his arm in the fashion of an uppercut that became an exclamation point. He then swung the can down with a violent, menacing speed, halting its rusted metal bottom just inches from one of the Buss’ eye sockets. Then he tossed it aside and moved like a man who just realized he’d left a light on, but didn’t know where.

“Anton—it’s Anton, right?—they don’t believe me when I say I’ll burn this place down. I tell them that’s what I’m going to do and they say what about all the good times—that we have history between us.” He removed a bank lollipop from between his teeth. “But I’ve never been a fan of history. This city should be a desert, but rivers were redirected and aqueducts erected—ain’t that some Roman shit! Yeah, they destroyed Eden to build this paradise. Hell! California was seized from the Mexicans. Before that, T-Rexes and triceratopses. I’m just the next in line of a line that coils and uncoils to coil again. I’m just this generation’s Yellow King. History— ”

Kobe turned to face the Busses again, rubbing the backs of their sweaty heads with his cool palms—he looked like a Messiah of sorts, except that his followers were bound and gagged. “History is a flat circle, and we’re just gonna burn it down one more time and then again and then again and then again. We’re gonna reduce it down to its Spanish-speaking armadillo roots and that’s when, I believe, we’ll all really understand skid row, meteorites, and extinction. That’s when we’ll have built something. That’s when we’ll have nothing—am I right? Fuck yeah! I’m right, I’m named after a damn steakhouse!”

The Busses cowered before their serpentine Savior. Antawn said nothing, but if he had, it would’ve been that he was impressed. For all his travels, he had always been a traditionalist. Going back to his days as a boy in Carolina, he had always been someone who admired virtuous paths and the building of monuments. But, with one monologue, he had converted to the disruptive cycles of destruction that Kobe Bryant enacted everywhere he went.

“Where you from? Oakland? DC? Maybe Dallas? You been around—I can tell.”

Antawn treaded lightly, and then he did what converts do—he denounced the past. “I’m not from anywhere.”

“You ever seen anyone like me?”

“The only one. . . . You hear that. . . . I’m the only one.” Kobe berated the Busses. “So why you wanna shortchange me? You know what I’m capable of—what I’ve done for you. Antawn, if you could be so kind as to unlock each of those footlockers for me. The key’s in the jacket on the back of that chair.”

He pointed.

Antawn picked the suit jacket off the folding chair. In the chest pocket, with a set of diamond encrusted brass knuckles was a small key. Antawn took it and walked to the foot lockers, lined up like choices in a game show. He unlocked the first and let out a gasp.

Kobe ordered Antawn to let the man out of the box and to get on with the other two lockers.

Antawn extended a hand to each man, helping each one out of his coffin. The first man was missing an ear, but Antawn recognized him as a Spaniard named Pau. The second man was a former bouncer at the club named Bynum. As he unlocked the third locker, a voice from inside called out to Kobe. When Antawn opened the chest, he was surprised by how comfortable the man appeared inside what was essentially a wooden crate.

The man poked out his head, “Kobe. . . Kobe, man, I can stay in longer if you need me to, just sayin’, I’ll do whatever.”

“Metta. . . Metta. . . Metta. . . of course you would.” Kobe walked to the crate slowly, hands reaching behind his own back, towards his waist. He pulled out a gun, either a .38 or a .45. Antawn wasn’t sure. This was not his world.

“Kobe, man, you need me to stay in the crate—I will. Need me to go for a walk—I will. Want me to roll over—I’ll do that too, bro. Want me to play fetch— ”

A bullet interrupted Metta’s words, as his head collapsed back into the wooden chest, which now had a bullet hole in one of its side panels. Blood seeped out. “Send him to New York.” A second gun shot. “Send him to Philly.” A third gun shot. “Send him to Chicago.”

Antawn looked to either side of himself, like a kid frightened to cross the street.

“Yes, Mr. Jamison, I want you to do it. Or, choose which box you yourself can fit inside.”

“But I never. . .”

“Never what? Seen a shot you didn’t like? All those years singing in my man Gilbert’s club and you never seen something like this? The only difference is I possess purpose.”

Kobe started wiping down the barrel and handle for prints with a white towel. He tossed the gun aside.

“Now haul those bodies upstairs.”

Kobe turned towards the Busses. They shook with fear; however, their voices too hoarse and too dry limited their objections. Antawn locked each footlocker with the same key that had unlocked them. He then set about moving the dead weight up the stairs and into the alley behind the club. As he did so, he could hear two voices, each somehow distinct, foreign, and familiar. In the basement, Kobe railed on about the San Fernando Valley and Mexican armadillos, while, upstairs, Stevie Nash sang to an empty room; her voice moving through the rafters like a rusted angel. After he hauled the third crate outside, Antawn waited for the folksinger from Arizona to wander backstage.

“You gotta get out of here.”

“And go where?” she laughed, drunk.

“Anywhere.”

“You as drunk as I am? ‘Cause you sure do sound it.”

“I ain’t sober—”

“Well, why am I gonna listen to you then?”

“Don’t you have a son? What’s his name? Amar’e. You should go be with him.”

“I don’t even know where he is.”

“Find him.”

“I know you’re a blues singer and therefore a bringer of sadness, but that’s some sad history you’re dumping on me there. I had a son. Now all I’ve got is a shit job, a bad back, and even worse memories.”

“Damn it, Stevie, he’s burning the place down!”

A rumble came from inside the storage closet and then a burst of flame. Antawn didn’t remember much after that, except the scars and maybe Stevie singing, “Burn, baby, burn!” If indeed she did sing those words, it was the only time he could remember her singing anything other than folk music, much less disco, and now—now the voice was catching fire with his memories.

Melo, New in town

(Image by Mike Langston)

For eighteen hundred miles the gum smacked in his ear with indecency, and each time the bubble burst, he found it more obnoxious than the time before, more obnoxious than anything in his life, including the local sheriff telling him, “It’s time to move, Melo. Time. To. Move.”

The gum smacked again, and he turned to face the woman who had turned him in, who had ruined a very good thing in his life. He turned to her—inhaled—and didn’t say a goddamn thing. He swallowed his pride. He steered. He moved on. Life would be good again.

As he came to the bridge his Blaxploitation tank of a car was nearly exhausted from guzzling gasoline and chewing up asphalt. The sun rose over New Amsterdam. He could see it through the suspension cables, golden bands descending on the cage of the city. He had come east. The sun was rising. Symbols were aligning. The new day was not a figment but material. He braked for the man standing on the bridge, with his fist out and thumb aimed at the sky.

“Why you stopping’, Melo?” asked the woman in the passenger seat beside him. Her lips glossed red and a pink bubble ebbing from the space between. Its pink belly expanded with planetary promise. Then, SMACK! It burst between them. “We don’t got the time and we don’t got the room. Keep driving.” She whipped her index finger in the direction beyond the windshield.

“Looks like the man needs our help,” said Melo. He was in need of friends. She really had cost him everything.

The man stood next to a smoking taxi car embedded in the very stone of the bridge. Melo coasted to a stop and cranked down the window.

“Should’ve splurged on those automatic windows,” said the woman, followed by that quick bursting crack of perpetual string theory. Melo ignored her—she was rarely satisfied. A part of him missed the mountains and their permanent peaks.

“Yo, you need a lift?” called Melo to the man, but the man didn’t say anything. He just stared at the large black hat in his hands as if it were possessed with magic, voices, or magical voices. “Yo, man, you need a lift? That taxi’s done.”

The man put on the black hat, and Melo found himself unable to look away.

“Look, man, you give me that hat, and I’ll give you a ride—we’re headed into the city—right into its great, big ugly heart, you hear me?”

The woman in the passenger seat yawned.

“I hear you,” answered the man standing on the bridge, his voice more present than his thoughts.

Melo got out of the car, opened the back door, and moved some suitcases around in order to fit this long skeleton of a man amongst the luggage. He then took the hat off the man’s head. The man did not seem to notice, his stare was steeled to the river’s current. “Sit in back, why don’t you?” Melo escorted the man into the back of the car. “Watch your head.” As Melo climbed back in the driver’s seat, he tried on the hat, checking himself out in the rear view mirror. Fuzzy dice hung from it like a pair of cubed testicles from another era, and he couldn’t help but grin. “Looks good, don’t it?”

“Why you wearin’ some other dude’s hat?” Sigh of a pink planet, and then, POP! “Probably got lice all in it!”

Melo shifted the car out of park and navigated the caddy towards the city. The man spoke for the first time, “He was there, and then he wasn’t. I didn’t even hear the splash.” Underneath the bridge, water rolled and rolled. Melo turned up the radio. He didn’t like the sound of the man’s voice.

Dwyane Wade’s opening credits

(Art by Todd Whitehead)

Eventually the financial crisis caught up with everything, including Wade’s own real estate dealings. Without anyone really knowing it, business had clearly peaked in 2006 and then it had suffered a rapid decline. By the time it bottomed out in the sudden depths of 2008, his investors had seized back their finances and stranded him with a stack of deeds for a paradise that no longer existed.

Since that day, though, gators had proven to be the least dangerous predators in the swamps of the Sunshine State. And yet, even real estate moguls could wilt in the insurmountable Everglade heat.

Mr. Haslem, hook scratching at his temple, had watched the firm’s last few years wear on Mr. Wade. The man no longer commanded a room a la Don Draper. Mr. Haslem and everyone else wrote the tension off as physical fatigue. “Why don’t you take a vacation, D-Wade?” they asked him. But he refused. What Mr. Haslem and others could not see, or he refuse to see, were the cracks in Mr. Wade’s cavalier facade. They also had no way of seeing his private doubts; the only evidence being a one sentence letter scrawled on plain parchment paper and devoid even of an official letterhead:

Mr. Dolan, I’m ready to hear your offer.

Wade signed the card and slid it into an envelope, knowing that if he sent the letter, he’d most likely be giving up the dream of owning and operating something built almost exclusively on his back (and with the help of one Patrick Sir Riley. Little did he know, however, what levels of guilt such a seemingly innocuous card would unleash within him.

That afternoon, he informed Udonis Haslem he would be leaving early. He donned a hat atop his head and walked the letter to one of those sidewalk mailboxes that harkens to some earlier, unlived age and gives off the suggestion that it could protect the mail from a nuclear holocaust, if only such an apocalypse might have the courage to step forward out of the dark. Then, he stepped inside a dimly lit bar and ordered drinks more popular in other decades. Maybe he hit on a waitress. Maybe he didn’t. Around sunset, he stood on a rooftop balcony watching a plane fly over the Atlantic.

He leaned towards it, with a drink at the end of his extended arm. The condensation slid through his fingertips. He watched the glass plummet onto the sidewalk below. When it smashed into pieces, a startled couple let go of each other’s hands and looked up towards the roof and beyond. He yelled back, “” and they had no idea what he meant.

*****

A stench of unwashed clothes, the natural odors of the body, vomit and alcohol, these were the odors that filled the room. On the desk was a near empty bottle. Around the trashcan were more bottles sucked dry; some of them broken. Mr. Wade had not left his room at the Knickerbocker in days. The blinds were shut and the curtains pulled tight. He was alone with the darkness and the letter he had received weeks earlier from Mr. Dolan in response to his own:

We’d be happy to meet with you.

Despite not knowing the nature of his New York business, Wade’s assistant, Mr. Haslem, had now rescheduled his meeting with Dolan’s office at least three times in as many days. The hotel room phone was off the hook. Wade’s phone was on silent. He only returned calls from Haslem, asking the man to order him room service. Yet Haslem could not order him room service because he did not know in what hotel Wade was staying. Who knows how the man continued to eat and drink? He wrapped himself in blankets;

He could see the shadow appear in the hallway light that slid underneath the door with that persistent creep of kudzu. “Go away!” he yelled, figuring the shadow belonged to some heretic maid come to change the bed sheets and vacuum the floor. “Go away! But bring me another bottle of Early Times! Leave it at the door! By all means, don’t knock. . . . uh. . . uh.” His voice trailed off into infantile groans, the sounds of the elderly, and he fell sideways on the floor. The room was spinning once more. And then he would lose track of time and space and imagine what the world must look like to a bird.

Hours later he would wake up and wonder: Was he at Niagara Falls? What was that sound of rushing water? Then he felt the rush of ice against his skin, running down the back of his neck, and he realized someone was forcing him underneath the bathtub faucet. He groped around with his hands. Dear God! Someone was trying to drown him. He fought for control, but the stranger’s grip was firm and strong. They had him by the collar and by the arm. They twisted. He shrieked. He growled, “Fuck you.”

“Fuck me?” The voice slithered like darkness in the light of the bathroom. “I’m your only friend. I’m the reason you haven’t drowned.”

“I HAVE A—meeting!” Wade tried to stand, but his legs failed him. He was wobbly, like his bones were made from chicken fat. “We need some food. Order some chicken cordon bleu—some champagne. Let’s celebrate!”

“And what is there to celebrate between us?” The man walked towards the sink, his pinstriped back to Mr. Wade. The man wiped his hands on a white monogrammed towel.

“The demise of the firm. My great migration north. The failure of empires.”

“This New York business is done. You’re coming back to Miami on the next plane.”

“But we have no money! The assets are all dried up or liquidated or—”

“You also don’t have a legitimate law degree, real estate license, or dental certificate. In fact, the closest artifact you have to one is me. I am your degree—your voucher—in this godforsaken world of virtuous pretense. You would do well to remember that. That, and the white sand and the tan bodies. New York is a bedlam of frost and bone. In Miami, there’s always flesh.”

Sitting on the bathtub ledge, cradling his head in his hands, Wade pleaded with the man, “But I’m done in Miami. O’Neal bled us dry.”

“We close one firm and open another. Wade & Associates, yes, that name is tarnished with rust-colored debt, but I have something else in mind. Let’s kick the can a little ways.”

Wade looked up. “What?”

“Obviously we change offices. New paint. Marble, granite, hardwood. Modern. We present not what we are, but what we will be. We feign old money, but we feign it like Gatsby—yes!—but without feeling inferior. We do all that, but we also change the playbill. We’re not running the same drama as before. This is different. It will need more panache. I’ve got something in the works, an idea, but first I need you to meet with these gentlemen.” He handed Wade a manila envelope. Wade opened it. The biographies of two men were typed up; one from Canada and the other from the Rust Belt. Copies of their drivers’ licenses were paper-clipped to the front of their biographies. “Meet with them. The one is on his way, most likely. The other you will need to seek out. Their names will have to receive top billing. We’ll get you back on the masthead as soon as we can. You understand.” And with these last words, Mr. Riley sat on the lid of the toilet seat, looked at Wade with those penetrating eyes and clapped his cold, dead hand onto Wade’s. “Take a shower. Sober up. I left a new suit on the bed.”

Wade did as he was told, as if his life were a script. As he showered, he thought of a movie from his youth, The Devil’s Advocate, starring Keanu Reeves and Al Pacino. The film was not a great one, just an over the top take on everything Faustian. Wade thought of the film’s climactic scene where Al Pacino’s Satan asks his son Keanu to have sex with his daughter, Keanu’s sister, in order to produce some sort of anti-Christ grandchild of the Devil’s. In the steam of the shower, Wade shook his head and told himself:

AI, Walking in Memphis

A chewed up dog pissed on the garbage can that stooped by a rusty fire escape. Imagine Napoleon dragging on all four paws to plant a French flag in midst of a wasteland, and you have what this mutt had accomplished. A thick sludge made up of what appeared to be either coffee or larva lurked in the curb. The whole street smelled of urine and fast food. Hot air crept up through the cracks in the sidewalk, as if the whole neighborhood rested over Hell’s furnace. At night, devils walked in and out of apartments and down rickety metal stair cases, making deals and bargains over souls and minds and time, whispering through televisions and crack pipes. The dog lowered its leg, poked its nose up in the air, and sniffed the new day, already cloaked in yesterday’s guilt. The canine barked at an oncoming car and then moped down the street passing by the window of a first floor apartment.

Flies buzzed in and out of the slits in the apartment window’s screen. An old man rested face down on a cot that sat beside the wall opposite the window. Next to the cot was an old milk crate, coated in dusty magazines and newspapers. Piles of old clothes littered the floor. They looked like they had either come from or were on their way to the local thrift store. On the floor below the window was an old television set, complete with an aluminum foil antenna and a knob for changing the channel. The television had not been usable since the switch over from analog to digital.

The man on the cot rolled over and placed his two feet on the floor. With his toes, he could feel how the floor needed to be vacuumed. Hard bits of dirt and old toe nail clippings nibbled at the bottoms of his feet. His head rested in his hands. The day was not met with enthusiasm.

He took an old pair of slacks off the floor and pulled them up to his waist. An old leather belt still wove its way through the loops; he tightened it to the third notch, to keep his pants from sagging like the young hoodlums that roamed the block outside his apartment. He didn’t bother changing his undershirt; it was only on day two, maybe three. He put a button up over it, and tucked it in. His shoes were well worn, and the laces felt like they might fall apart in his hands as he tied them. On his way out the door, he grabbed his hat and jacket. He looked like an old newspaperman, like he knew stuff in books but was smart enough not to tell anyone. The shoulders of the jacket showed a former strength, but they curled now like the cover of a paperback book that’s been folded in half. He passed the landlord, Mr. Stern, on his way out.

“I’m not running a charity, Iverson. You gotta give to get.” Mr. Stern said these words without looking up from his crossword puzzle. “You gotta give to get in this world.”

“Can you watch my door for me? Broke the lock last night when the key got stuck.” Allen Iverson was only half lying. The lock on the door was broken; and it did happen last night; but a key had never entered the lock. Allen had lost his keys on his way home from the bar, and had used his shoulder to force the door open, busting the lock. Allen didn’t remember the ordeal until he put his left arm through the sleeve of his dress shirt. The sharp pain of a sprained rotator cuff helped him to remember everything from searching the bar for his keys, from his regular barstool all the way to the toilet, to his impromptu decision to yell, “Geronimo!” while charging into his door like a buffalo with a stubborn limp.

Mr. Stern responded to the request, “Gotta give to get. Give to get.” He saved the rest of his vocabulary for his newsprint puzzles.

Allen eyed the gray sky as he walked down the sidewalk, wondering to himself, “How the hell did I wind up in Memphis?” He did not find the reasons to be all that revealing. He got laid off from his job at a Detroit auto plant because his age made him an insurance liability. When he first heard the explanation, he had planned on taking the company to court, but on his way home that day he had slipped on some black ice and thrown out his back. In court, the company’s lawyers demonstrated that Allen Iverson could no longer physically perform the task of lifting car doors hour after hour and day after day. They also shamed him with witnesses who claimed he may have been drinking heavily the day of his fall. When he went on the stand himself, Allen told the opposing lawyer, “What we talkin’ about? Drinkin’ after hours. Not on the job. Never on the job.” Allen lost the case, and moved to Memphis because it was warmer than Detroit, cheaper to live in than LA, and had a better bar scene than Charlotte. It was also as far as he made it on his way to Miami before his car broke down.

Memphis meet Mr. Iverson, the man without a destiny.

Allen walked by a chain link fence. He held his right arm out, and dragged his fingers along the metal. He walked as if each joint in his leg had a bullet in it; each step pressing bone to lead. The pain caused Allen to stop. He clung to the fence with both hands, and peaked through the diamond-shaped holes at some kids playing basketball on the other side. Two tall and gangly boys were picking teams. To Allen, they looked like teenagers. Moreover, their smiles looked like they were baiting the world to come close enough to their mouths to be swallowed, as if they were fish unafraid of hooks, as if they were mutant tunas that could prey on sharp metal in the river’s current.

“I’ll take Gasol. Who you got, Rudy?”

“Conley.”

“Thabeet.”

“That’s all there is, OJ. Who else am I going to pick? That old man with the limp? Puhlease. We’ll take you two on three,” the young man took the basketball he’d been dribbling between his legs the whole time and heaved it at the kid named OJ. “You other scrubs can go play over there.” He pointed to a backboard across the court with no rim. Streaks of brown marked where the rim should have been. As the game began, Allen thought how light the ball looked in the hands of these boys, like they were gods dribbling entire planets through space. A sharp pain in his back then reminded him what a toll playing Atlas can have. He turned from the court and walked on. It was late morning and time for a drink.

*****

When Allen walked out of a raggedy blues bar called The House of Mutombo, having had more than his share of a house concoction called the Stackhouse, he staggered on the deadbeat sidewalk like a man twice his age. A dog, tied to a parking meter looked and with its head cocked to the side, seemed to be looking at him. He didn’t have anything worth giving to the dog, so he started rapping:

I’m hittin anything in plain view for my riches

VA’s finest fillin up ditches, when gangstas turn to bitches

die for zero digits; I’ma giant yall midgets

I know killaz kill for a fee

that’ll kill yo’ ass for free, believe me

How you wanna die fast or slowly?

He paused, allowing the dog to judge his work. The dog bared its teeth and growled. Then it lunged at him, snapping its jaws and barking. “Alright, alright. Not a fan of the rap game. Alright, well, try this on for size. You see, I’m versatile.” Allen wound his arm up over his head and pretended to strum an invisible guitar. He dropped his knees like Elvis:

You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog

Cryin’ all the time

you ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog

cryin’ all the time.

Well, you ain’t never caught a rabbit

and you ain’t no friend of mine.

When they said you was high class,

well, that was just a lie. . . .

The dog howled, and Allen howled with it. A man who Allen could tell wasn’t from the neighborhood walked up and began untying the leash.

“That your dog?” Allen asked the man.

“Why else would I be untying it?”

“Oh, I don’t know. People steal all sorts of things that could belong to other people. You know, I had a job once.”

“Man, you need to lighten up on the drinking. Might even help your singing.”

“What you know about it?”

“I get around. Own some here. Own some there. I scout everywhere.”

“Oh, yeah? What’s your name?”

“Mr. Bryant.”

“Alright, Mr. Bryant, I’m gonna perform a little duet here with your dog.” Allen wound up his arm again, about to strum that fake guitar of his that was never out of tune, but never in tune either.

“Whoah, now. I think the dog and I have heard enough.” Mr. Bryant made a clicking sound to his dog and led the creature away on his leash. Meanwhile, Allen looked at his wrist, to check the time, but he wasn’t wearing a watch. He slunk back, hand on head, legs ajar, almost as if he were posing like Elvis, and glared woefully at the sun. “Still got plenty of time.”

He headed towards an establishment called the Grindhouse, but when he got there, the sign read: CLOSED for Renovations. The company credited for the work was called Z-BO CONSTRUCTION BROS. The company’s apparent slogan: We Don’t Bluff. “Well, I don’t either,” Allen said, and he kept on walking.

Linsanity & the sounds of the city

The wheels of the car rolled on, but they did not touch the road. Physics and friction became occupants of fiction, existing as fantastical laws in the canyons of the mind. Melo witnessed the smoke and mist of the city’s streets and felt himself adrift on a river directed by an ego equivalent of Francis Ford Coppola. Lightning flashed in the street level thunderclouds. Drums banged and chants swirled. Tambourines chattered and colored rags clung to the street signs and telephone poles that rose up to great heights like timber from the watery graves of old fishing villages, but they presented no docks. They held no welcome. Melo did not bring the car to a halt; the car halted itself.

The teeth became visible before the body. The teeth and the throat, chomping in the misty darkness. Then the eyes. The eyes swirled in pigmented streaks of green and yellow. The eyes flashed from a crimson mane. The drum beat became syncopated, and the tail of the great dragon twisted and spun through the road like a silkworm come to eat the world. Faces flashed before the windows of the car—faces possessed with true belief. The back door opened, and Amar’e stepped out from the backseat. He followed the dragon’s tail, his body possessed with the rhythm of the scales and the lightning and the tambourines. Melo rolled down the window, “Hey! Come back! Where are you going?!”

But the man was lost, like a young Lawrence Fishburne in midst of a Rolling Stone fever dream.

Melo undid his seat belt. He reached for the door. He felt a hand on his arm and the sharp pang of long, acrylic talons piercing his forearm. “You ain’t goin’ out there! Nuh-uh. You ain’t leavin’ me!”

“But didn’t you see him? He just disappeared into that—into that—“ He wanted to say the belly of that beast. He almost said fog. He ended up mouthing thing. He wound up speechless.

“He also stole back his hat. I say good riddance.”

Melo groped at his scalp—there was no black hat—only row after row of braids. He wanted back that hat. He needed it. “I’m going after him.” He spoke to the gray mist as much as to the woman beside him. Perhaps it wasn’t even the hat he wanted, but to be reinvigorated. A moment ago he had seen a golem rise up from the backseat of his car, from a grave of suitcases and old air fresheners, and then dance across the threshold of another world with such blissful exuberance that he now felt anything outside of that passing storm did not exist. He was jealous of the moment that had just passed before him, and from his jealousy he rose and followed the tail of the dragon, the flashbulbs of lightning, and the knocking of the drums.

Mattresses and couch cushions lined the sidewalks. People had taken to sleeping outside in the fervor of this insane moment. When the heavenly clouds of the street parted like drapes, the streetlights glowed like full moons. Every block was an orbit. Every few blocks was a solar system. Every mile a galaxy. And in pursuit of the resurrected body and the miracle-working dragon, Melo passed in and out of time, following the strands of smoke that clung to the concrete and brick of the city like wisps of some omitted god’s beard. On every corner, men in black hats and flannel shirts recited long poems woven from the interspersed lines of Testament and Naismith. People called out to these bearded poets and their thick-rimmed glasses with Amens and then proceeded to toss not just dollars but entire wallets—credit cards and all—into peach baskets mounted on street lamps.

Some called it Grantland. Others said it was unnameable. Melo thought it was beautiful, and yet he kept his distance, buffering himself with something close to jealousy.

And the crowd repeated, “The Lin is near! We shall be released!”

Then the man went back to painting on the wall. He dropped his brush, held two fists in the air, and throttled some imaginary baby before repeating, “The Lin is near! We shall be released!”

And the crowd would respond before this seven-foot Elijah, “The Lin is near!”

Melo turned to the nearest person confused, but not wanting to be confused, “What the hell is the Lin?”

“What the hell is the Lin?” repeated the man closest to him. “What the hell is the Lin?”

Then they were all around him, laying hands upon his clothes and body, all speaking at once: What the hell is the Lin? What the hell is the Lin? What the hell is the Lin? What the hell is the Lin?

They picked him up and placed them on their shoulders. He was eye to eye with the sweating prophet.

“Do you not know the Lin?” asked the man, his eyes wide and white as canvases.

Melo swallowed, unsure of what was taking place. “No. . . I. . . do not know.”

The large man turned his face to the sky and bellowed, “Take him!” Then he looked into Melo’s eyes once more, “Take him to bear witness. Tell the dragon, Patrick sent him.” Then the crowd carried him off, chasing after the dragon, chanting in tongues. The sounds of the city.

Years later, it was all forgotten, washed over in a quaking sea, the “Harlem Shake,” and the Church of Porzingis.

Kevin Durant & Russell Westbrook, Young Guns

(Image by Mike Langston)

The step creaked with arthritis, and the railing appeared ready to give like a knee. The shadow that followed the groans of the staircase’s old age was nothing but a silhouette of skin and bones, falling back into the depths of the forgotten first floor. Climbing ever so slightly, one groan at a time, the shadow trembled like a thin curtain and appeared frail enough to need a cane. But the body that shaped the gloom moved with a surprising spryness. Captured in Kevin Durant’s ascent of the stairs was the worn out, tired idea of the hero rejuvenated by a six foot ten inch Jacob’s ladder of taut muscle and sinew.

As this young U.S. marshal climbed, he held his glock out before him, ready to fire, just like he was taught at the Academy. When he came in the front door, he had heard whispered movements upstairs suddenly stop, as if the front door had ushered in a resounding shhhhhhh. His partner, a fast riser in the ranks named Westbrook, manned the backdoor. If someone had run out that way, Durant was sure he would have heard shouts and shots fired. But he hadn’t, leaving him to conclude the interloper was still in the house, waiting upstairs behind double doors, in the closet, under the bed, or behind the dresser. Probably armed. Definitely dangerous. Holding his breath. Finger on the trigger.

Durant paused about a foot from the door, took his left hand off his gun, hesitated, and touched the iron door knob as if the building might be on fire and he were checking for a safe exit.

The knob felt cold as the wind outside—Durant felt a craving for coffee, black, to warm his blood. From the slit between the two doors he smelled tobacco burning. A cigarette snuffed out just as he entered the house. He turned the door knob slowly and swung open the door, eyes locked down the barrel of his gun.

*****

U.S. marshal Westbrook used the tip of a ball point pen to scrape dried dog shit from off his shoe’s sole. He went about the process with a deliberate patience, much like a dentist, or an archaeologist, as if the rubber he was unearthing might be of value.

As he did so, he propped his left leg over his right in a manner that suggested no matter how long he waited he would never be used to it.

In such places, most people tighten like rubber bands stretched around too much paper. Westbrook did too. Thing was, he never relaxed. He was always caffeinated.

After a time, he noticed that his scraping motion was in double time with the waiting room clock’s second hand. This mechanical choreography made Westbrook uncomfortable. He stopped, put the pen in his coat pocket, and uncrossed his legs. At first, he appeared to not know where his hands should be placed, so he stood and walked past the elevator and towards the water fountain. He leaned down and took a sip. The water tasted of metal. He wondered about its lead content and then pivoted back towards the green chair he had recently abandoned.

“Man, what the eff are you doing in my seat?”

The kid looked up at him.

“Seriously, you have to move.”

The kid spat his retainer into the palm of his hand. “I’m waiting.”

“We’re all waiting.”

“Is that your gun?”

“If it wasn’t my gun, then why the hell would I be wearing it?”

“My dad was a sharpshooter.”

“I don’t care who your dad was–”

“Have you ever shot anyone?”

“Will you get the eff out of my chair?”

The kid forced the saliva drenched retainer back into his mouth and covered his ears. Westbrook yelled an expletive and walked back towards the water fountain.

As Westbrook reached the elevator, it opened and a nurse stepped out to clear the hallway. As the other nurses and one doctor pushed the gurney out the elevator, the back wheel caught on the edge of the door, halting its momentum, prompting one the doctor to growl, “Damn it! Nurse Brooks! Watch where you’re going! This man has a thin line to walk without us banging him into doorways.”

As they passed, Westbrook noticed the name Shawn Kemp on the doctor’s clipboard. He looked down at the patient’s face, with its wide open eyes, like saucers. Shawn’s pupils were faint drops of coffee, barely discernible, almost as if they were staring inward and not out.

The sight of this stranger’s diminished stature caused Westbrook to ponder his partner’s eyes as they had looked up at him from a pile of loose bricks.

Were Kevin’s pupils that faint? No, Kevin’s pupils were dark and dilated, not squinting to see some inner light. No, Kevin was in much better shape than this Shawn Kemp character.

Westbrook returned to his chair, crossed his arms. Then uncrossed them. He raised one fist. Then another. He looked like a man working either on Janet Jackson choreography or some long forgotten handshake. As he lost himself in energetic agitation, the clock contemplated the finite number of coffee cups in a person’s lifetime.

The blinks. The winks. And all the openness in between.

Detective Durant had gone into the brownstone alone.

He had told Westbrook to circle around back and watch for anyone coming or going, and Westbrook had done just that. Westbrook had waited outside the row houses leaning and stumbling into each other like drunken lovers on a brisk ferry ride.

He watched the dark windows and doors, wanting to light a cigarette, but knowing that to do so might get Kevin killed. This case had taken up months and then years of their lives. Not once had they been this close to apprehending their suspect: a man that the rest of the department referred to as a shadow—an obscurity no one notices until it’s all around you, like the blackness of night. Most of their suspect’s victims were found with their throats slit and a profound smile on their faces, as if in death their jaws became beset by pearls.

The thought of the last body they’d found—a huge man, with a huge smile, named Dwight Howard—had crept into Westbrook’s mind as a chill fell over him. Standing in the street, he could still picture the man’s arms and legs pulled tight to each bed post by a knotted dog leash. Something sickening.

If this shadow could slay a behemoth like Howard, then what chance did his matchstick of a partner have?

With these images in his head, Westbrook had drawn his gun and headed for the back door. There, he had fumbled with the doorknob and was about to kick it open, when, with his leg already raised, he had heard a window jostled open from above, followed by a single gunshot.

Westbrook had then backpedaled, almost tripping over the curb. Above him, a body had slithered onto the rooftop, hoisting itself up using the brownstone’s chimney for leverage. A brick had then come loose just as the body stood up on the shingled rooftop and fell three stories, landing about ten feet or so in front of Westbrook.

He backed away, searching the rooftop’s line for the serpentine shadow, but had seen nothing other than the chimney’s outline.

“Russell, you still out there, man?”

“Yeah, Kevin, he’s on the roof!”

“You gotta line on him?”

“If he moves at all from behind that chimney, he’s a dead man.”

“You hear that, Black Mamba? There ain’t no where to go.”

Silence.

Westbrook had been unsure what the next best move might be. The Black Mamba could not come out from behind that chimney to run from one rooftop or another without risking a gunshot wound, and, if he had jumped off the front, there were two unmarked cars surveilling the the road. The fugitive had nowhere to go. The only question remaining was how long a man on the run could wait on a dry rooftop. Westbrook envisioned the next day, around noon, and how hot the sun would be and how local law enforcement would be called in to talk their target off the roof. In other words, this was it: their only chance to take the notorious killer mano-a-mano.

The line had been drawn in the moonlight.

Westbrook watched the framework of the chimney, like a cat waiting in the high grasses for its prey. He had imagined the Black Mamba on the other side of the chimney’s brick walls staring back at him the way cobras stare through glass plates at the zoo, hissing at all the children who slap the window, smearing their dirty fingerprints all over it. But he would not be denied his chance for a showdown.

Sitting in the hospital, flecks of dog shit fell from the bottom of Westbrook’s shoe to the floor, and the words descending down the hall from one nurse to another:

“That Kemp guy isn’t going to make it.” “What about the long, skinny guy they just brought in?”

Durant reached his hand up from the window and slapped the gutter, gave it a tug, found it sturdy, and began pulling his body up onto the roof, pushing against the window sill with his legs. Durant’s decision to act, to poke the cobra inside its basket, was greeted by a grating sound. Westbrook watched as the bricks slid in place like the slow wavering of a mirage.

“Kevin, man, those bricks are movin!’”

Durant’s foot slipped on the sill; he was hanging off the gutter by only his arms, no support.

“I’m not the Black Mamba!” screamed the chimney, “”

A cascade of bricks subverted this exclamatory statement, raining down like chunks of hail around Durant’s head. The gutter gave way from the onslaught, and Westbrook watched his partner fall three stories, landing on the ground underneath a pile of rubble.

And he fired at the rooftop shadows, hitting nothing.

After emptying his clip, Westbrook rushed to the pile and began heaving bricks off Durant’s body, yelling a combination of pleas for help and threats at the universe: “Help! Man down! Help us! You bastard! You fuckin’ bastard! Help us!” Westbrook yelled until his syllables became inaudible in space.

“We’ll get him, Russ,” whispered Durant, “I ain’t dead, just down.”

The look in his partner’s eyes had looked as infinite and desolate as the night sky. He could see no stars, only haze from some lesser light. If he had been more religious, he would have thought that Durant had seen something in the fall, that before him was a man becoming the same thing he had hunted, but Westbrook dismissed these ideas by closing his eyes and falling silent as the stones entombed around his partner. He had come to believe in himself and himself only. Durant’s eyes were open, but Westbrook saw the truth.

Kawhi & the typewriters