Introduction

Guantánamo Bay may be only a few hundred miles from the U.S. mainland, but its isolation, dated infrastructure, and exclusive military control make it a uniquely cumbersome place to conduct a trial—let alone some of the most complex, politically sensitive cases in our country’s history.

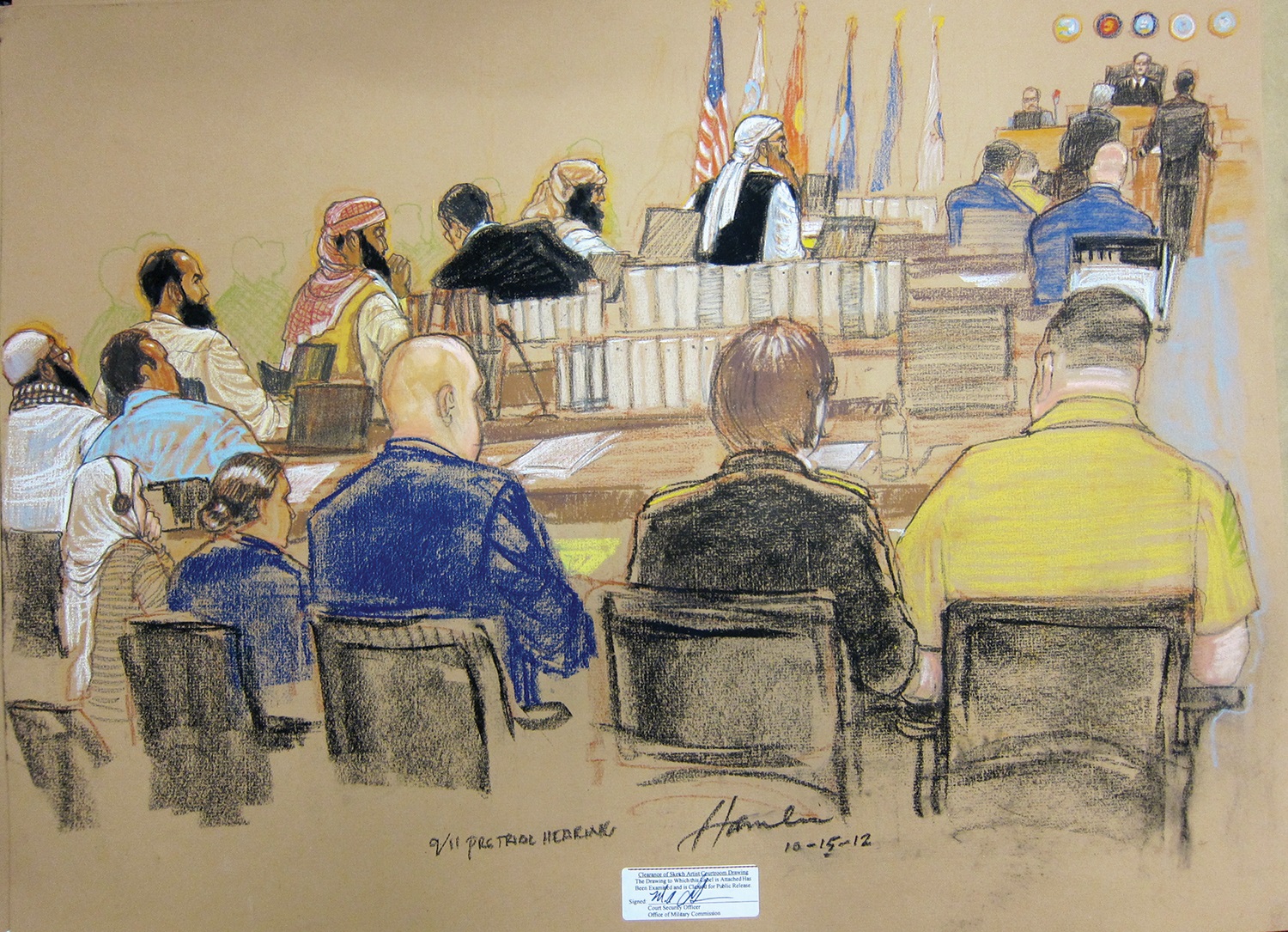

The proceedings at the GTMO naval base, in the Expeditionary Legal Complex courthouse, should be showcases for American jurisprudence at its fairest and most defensible, opportunities not just to prosecute those we suspect of harming us but also to demonstrate to the world how a nation founded on due process responds to crimes of war in an age of terror. Instead, more than 14 years after the September 11 attacks cut short 2,977 lives, seven years after the first filing of charges, and nearly four years after the commencement of pretrial hearings, the 9/11 case—like the two others underway, for the USS Cole bombing and the al Qaida-led assault of U.S. troops on the Afghan battlefield—has moved at a dismal pace.

We are not assigning blame or choosing sides, much less advocating for a particular outcome. Everything moves glacially at Guantánamo, whether the disruption is a hurricane or a toothache, revelations of government eavesdropping or detainee objections to contact with female guards. We worry, however, that these chronic delays—the inefficiency, the expense, the uncertainty over something as basic as a trial date—are undermining the legitimacy of the Military Commission process, and beyond that, our nation’s credibility on the world stage. By our count, Guantánamo’s three military judges conducted a total of just 30 days of on-the-record hearings in 2015. That matches the halting clip previously documented in an internal Pentagon memo, which tallied 33 days of hearings in 2014, preceded by 34 days in 2013. Regardless of one’s political views or position on the detention camp’s future, the on-again, off-again pursuit of justice, for at best a week or two every other month, serves nobody’s interests, neither deciding guilt nor doling out punishment nor affirming the integrity of our legal system.

We know this firsthand. Since 2013, the Pacific Council on International Policy has sent 17 members to the Guantánamo proceedings as official nongovernmental observers; together, we have spent 90 days on the island. Our GTMO Task Force is a bipartisan group, mostly practicing lawyers, though some of us have government, public policy, academic, and military backgrounds. What we share is a concern over the sporadic schedule we have witnessed at Guantánamo and a desire for concrete, pragmatic remedies that can fairly and transparently expedite a just resolution.

And after studying this issue over recent months, we can unanimously recommend a common sense solution: empower federal judges to preside over the Military Commission trials.

While we recognize that the intricacies of these cases and the particularities of the military codes governing them resist an easy solution, we believe that experienced current or retired U.S. District Judges—assigned full-time to Guantánamo—could apply case-management techniques that would go a long way toward clearing the logistical and procedural hurdles that have stymied the military’s commuter judges. Many federal judges, versed in the protocols for reviewing classified evidence, have already presided over high-profile terrorism trials in their own courts, guiding them to fair, final conclusions. As a group composed largely of attorneys, some of whom routinely litigate before federal judges, we can attest to the temperament of those who wear that robe: their impartiality, their gravitas, and their insistence that all parties keep to a reasonable schedule. Because they are civilians, moreover, federal judges would not create any improper “command influence” perceptions; their independence would be beyond question.

To further equip federal judges to advance the interests of justice at Guantánamo, we propose four additional steps:

- Technology. Permit stateside counsel to participate in routine pretrial matters and conduct attorney-client communication via secure videoconference.

- Timeline. Require each judge to set the earliest feasible date for trial to begin.

- Victims. Invite survivors and victims’ families to testify now, creating a record of their loss for the court if and when sentencing occurs.

- Openness. Encourage engagement and accountability by making the Guantánamo proceedings available to the public via broadcast or Internet streaming.

Again, we have made a deliberate choice to focus on workable, depoliticized measures directed specifically at Guantánamo’s three ongoing cases—Khalid Shaikh Mohammed et al., Abd al Rahim al Nashiri, and Abd al Hadi al Iraqi—recommendations that will continue to be relevant regardless of whether the detention camp remains operational or is ultimately moved or shuttered. Most of our task force members have expressed strong feelings about the broader issues that have made Guantánamo such a fraught symbol, including the indefinite imprisonment without charges of some detainees and the prolonged detention of others despite their clearance for release. Those concerns, which speak to the values we share as an open, democratic society, have animated our every discussion. Yet they ultimately go beyond the mandate we have adopted here, which is to identify tools for refining and, where necessary, repairing the legal machinery that has already been set in motion.

By keeping our aim narrow, we hope to avoid the inertia that has greeted other well-intended reports on Guantánamo’s fate, and instead steer the discussion toward practical, realistic solutions in this divisive election season.

I. Justice Delayed

In November 2009, when then-Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. announced his decision to try suspected September 11 architect Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and four alleged co-conspirators in the U.S District Court for the Southern District of New York, just blocks from where the Twin Towers once stood, he declared it the most appropriate venue for “what is truly the trial of the century.”

Today, the quest to prosecute KSM—the terrorism-related case that will say the most about our American brand of justice—is barely a blip on the national consciousness. As we know, Holder’s determination to bring charges in a civilian court was met with a storm of political pushback, including a congressional ban on relocating any Guantánamo detainee to the U.S. mainland. That put matters back again before a Military Commission, the war-trial process convened under President George W. Bush and revised under President Obama. And there on Cuba’s eastern tip, the case against KSM—captured in 2003, transferred to Guantánamo in 2006, arraigned in 2012—limps along, without so much as a trial date in sight.

In 2013, the prosecution predicted that a trial could begin as early as September 2014 and, despite the dearth of pretrial discovery, asked the military court to issue a placeholder scheduling order “so the parties can properly plan for trial.” The judge presiding over the KSM case, Col. James L. Pohl, declined to commit to an unrealistic date, calling the request “not within the realm of possibility at this juncture.” By 2014, defense attorneys were no longer certain that a trial could even begin in 2016. At a recent pretrial hearing, in December 2015, the chief prosecutor, Army Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, was unwilling to offer any prediction, other than to insist that movement toward a trial date was occurring in a “methodical” fashion. Defense counsel countered that, at this point, “2020 would be optimistic.”

Just about anything that can disrupt progress at the Guantánamo proceedings has.

(The al Nashiri case has had several trial dates, the most recent in February 2015, but his proceedings have been sidelined while the government pursues appellate challenges to multiple rulings. No trial date has been set for al Hadi, the only one of the three cases not eligible for the death penalty.)

Just about anything that can disrupt progress at the Guantánamo proceedings has. Assembling all the parties on a Caribbean island—reached by a three-hour military charter flight from Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland—is itself a trial at times. Legal teams, including the military judges, occasionally spend as much time in transit as they do participating in courtroom proceedings. Schedules are set, often with months-long intervals, then scrapped. Hearings have been canceled even after participants and observers have already been airlifted in. In 2012, a train derailment in Baltimore damaged a fiber-optic cable that supplied Internet access to the Navy, forcing a 24-hour delay in the KSM proceedings; the next day, with Tropical Storm Isaac bearing down on Guantánamo, everyone scrambled back to the mainland, not to reconvene for another seven weeks.

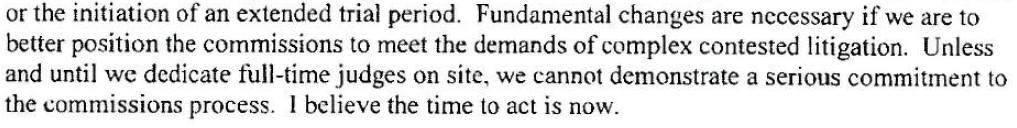

Concerned that only 108 hours of on-the-record hearings had been conducted in 2014 for all three prosecutions combined, the official overseeing the Military Commissions recommended that military judges be required to relocate full-time to Guantánamo and preside exclusively over the war trial to which each was assigned. Retired Marine Maj. Gen. Vaughn Ary explained that “fundamental changes” were necessary if the military hoped to demonstrate a “serious commitment” to the “efficient, fair, and just administration” of ongoing and future cases there.

Gen. Ary’s mandate, which to a civilian audience would appear to be a modest step toward conscientious case management, played differently within the military. After defense attorneys objected to the Pentagon’s meddling—and each military judge determined that the move-in requirement could be perceived as unlawful influence—Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert O. Work revoked the order; days later, Gen. Ary resigned.

The defendants, often contemptuous of the proceedings, have manufactured their own delays. At KSM’s arraignment, for instance, he and his confederates insisted—to Judge Pohl’s disbelief—that their entire 87-page charge sheet be read aloud, an exercise that consumed nearly three hours. Detainees have sidetracked the hearings with complaints of strange noises and vibrations in their cells, and they have dragged the court into debates over whether their refusal to be escorted by female guards constitutes misogynistic foot-dragging or a “sincerely held religious belief.” When suspected 9/11 terrorist Walid bin Attash abruptly announced that he wanted to fire his defense team and represent himself, explaining to the judge that “so many issues… take precedence over what is happening in this courtroom,” his attorney said she had “no idea” how to advise him, given the Military Commission’s abbreviated legal history.

The government’s intrusions have further hindered progress. Judge Pohl was dismayed to discover, in 2013, that “some external body” was monitoring the proceedings and, without his knowledge or consent, had hit the mute button controlling the audio feed, which runs on a 40-second delay to prevent leaks of classified information. A few months later, the prison camp conceded that a smoke detector in an attorney-client meeting room had been equipped with a hidden microphone—one of several confidentiality lapses that defense lawyers have protested—although prosecutors insisted the device had not actually been used to snoop on privileged conversations. That was followed by the government’s acknowledgment, in 2015, that an interpreter assigned to the defense had previously worked for the CIA. (“I cannot trust him,” complained accused 9/11 conspirator Ramzi bin al Shibh, alleging that he recognized the linguist from a secret CIA prison. “We know him from there.”) And that came on the heels of the FBI’s attempt to infiltrate al Shibh’s defense team in 2014 over a suspected security breach—revelations that effectively derailed the KSM trial for a year and a half.

“Not only is there no end in sight to the military commission,” defense attorney James Connell told reporters, “there’s no middle in sight.”

Looming over much of the pretrial holdup is the specter of classified intelligence: millions of documents detailing the U.S. government’s harsh treatment of the defendants. It is information that the prosecution argues could compromise national security if disclosed—and that the defense maintains is essential, especially in a capital case, to mitigating their clients’ culpability. Even if found guilty, KSM and the other 9/11 defendants would be given “broad latitude” under Military Commission rules to present mitigating and extenuating evidence at their sentencing—and as their attorneys have already argued, “torture pervades everything.” In short, they hope this information will convince a jury to spare their clients’ lives.

Federal courts already have a tool for striking an appropriate balance: CIPA, the Classified Intelligence Procedures Act, which provides a framework for weighing the government’s secrecy interests against a criminal defendant’s right to exculpatory material. Although CIPA has been incorporated into the Military Commissions, successfully applying its provisions to evidentiary disputes at Guantánamo, where the volume of sensitive information is unprecedented and the interruptions are unrelenting, has proved an elusive task.

A recent example we witnessed firsthand: At the December proceedings for the 9/11 case, Judge Pohl asked for oral argument on a defense motion to compel the prosecution to produce documents related to White House or Department of Justice authority for the CIA’s Rendition, Detention, and Interrogation program. It was first filed three years earlier, in December 2012, and for a year and a half, the defense complained, the prosecution had responded with “absolute silence.” As the transcript of their courtroom exchange confirms, Judge Pohl appeared frustrated as well, noting that he had before him a motion to compel, “and no reasons not to grant” it.

The prosecutor, Gen. Martins, took exception to the defense’s accusations of stonewalling, insisting that his team knew its discovery obligations and had been “working seven days a week trying to provide this.” Rather than address each defense request individually, however, he argued for a “consolidated” approach to producing all pending rendition-related discovery and asked for another nine months—until September 30, 2016—to complete it.

“Are you just not going to—you don’t want to address… [the motion to compel] at all then…?” Judge Pohl asked.

“I don’t,” Gen. Martins said.

A bit later, the defense tried to nudge Judge Pohl into taking a firmer stance. Al Shibh’s attorney explained that “it would be useful for the military judge to rule on motions to compel in the ordinary course so that it would define the obligations of the prosecution.”

Judge Pohl declined the invitation. It was true, he acknowledged, that the government was seeking some leeway, but at least on this occasion, the court was not going to force the prosecution’s hand: “I said okay, you can do that, okay, this time, okay.”

Although the complex Military Commission rules and still-evolving legal interpretations of them have had a hand in these delays, other agendas sometimes appear to be standing in the way. The government is surely reluctant to air the harrowing facts of its torture program, evidence that could prove disastrous in the court of international opinion even if it leads to convictions at Guantánamo; defense attorneys, meanwhile, know that even if they can expose those embarrassing details, the closer a trial actually looms, the closer their clients are to facing death.

As the Los Angeles Times recently concluded, articulating a perception that some of our observers have detected: “Neither side seems all that eager to go to trial.”

II. Enter, Federal Judges

We have revisited the fitful progress of these Guantánamo cases not to point fingers but to point a way forward. We have great respect for the military and its high judicial standards, including the countless military judges who serve their country honorably. But these are unusual proceedings, a new test of American justice in a new era of conflict, and they call for trial judges with the experience to appraise classified evidence and the latitude to embrace an expedited calendar. So many of the logistical and procedural snags we have witnessed strike us as avoidable, or at least readily ameliorated, if a few structural—and, we think, uncontroversial—remedies are adopted. First and foremost: put federal judges in charge of the Military Commission trials.

As a group primarily of lawyers, many of us litigators who have appeared in U.S. District Courts across the country, we have a special appreciation for judicial authority and discretion—all the more so at the federal level, where lifetime appointments protect judges from political interference. Federal judges rule their courtrooms through a combination of constitutional powers, procedural rules, management skills, and no-nonsense temperament. In our experience, no federal judge would tolerate the delays and detours that have characterized the Military Commission prosecutions thus far. At a minimum, if federal judges were appointed to serve at Guantánamo—to relocate to the naval base and preside full-time over the three ongoing cases—we are confident they could expedite the proceedings to a point where a viable trial schedule would come into focus.

We know this, in part, because federal judges already have a track record of successfully resolving some of the highest-profile terrorism cases of our day. The Center on Law and Security at New York University’s School of Law examined a decade of DOJ prosecutions since September 11, 2001, and found that of approximately 300 cases related to jihadist terror or national security charges, 87 percent resulted in convictions. Those figures do not include more recent cases, such as the prosecution of Osama bin Laden’s senior adviser and son-in-law Sulaiman Abu Ghaith, whose 2013 arraignment before the Southern District of New York’s legendary Lewis A. Kaplan inspired commentators to observe that the judge “was in complete control of his courtroom.” Indeed, in the span of about 18 months, Abu Ghaith was captured, tried, and sentenced to life in prison. As Attorney General Holder said in a statement, the “trial, conviction and sentencing have underscored the power” of the civilian courts “to deliver swift and certain justice in cases involving terrorism defendants.”

Contrast that with the record of the Military Commissions, which have won only eight convictions since their inception—four of which have already been overturned on appeal. Unlike civilian courts, the Guantánamo tribunals allow for certain kinds of coerced statements and hearsay to be admitted, exceptions that prosecutors contend are essential to bringing the high-value detainees to justice. But Military Commissions at the same time are available only to prosecute specific crimes of war, a limitation that has served as the grounds for several of the successful appeals.

What we do propose is sending judicial officers to Guantánamo who are uniquely qualified to bring the cases to swift and fair resolutions. In other words: empowering federal judges to apply Military Commission law.

Although many of our task force members would support trying the Guantánamo cases in the federal courts, we recognize the political and legislative barriers to bringing the defendants onto U.S. soil, and do not propose to challenge Congress’s clear opposition to doing so. Nor do we propose to dismantle the Military Commission mechanisms already in place, which for all their untested and occasionally confounding procedures, still have the ability, we believe, to produce just, credible verdicts. What we do propose is sending judicial officers to Guantánamo who are uniquely qualified to bring the cases to swift and fair resolutions. In other words: empowering federal judges to apply Military Commission law.

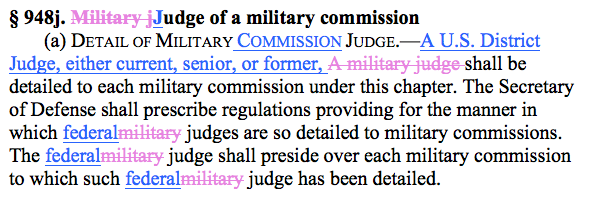

We recommend therefore that the Military Commissions Act of 2009 (MCA) be amended to require the appointment of U.S. District Judges for assignment to Military Commission cases. Specifically, the MCA should direct the Convening Authority—the military official designated by the Secretary of Defense to oversee the Military Commission process—to assign current, senior, or former U.S. District Judges to preside over the Military Commissions. This could be accomplished by minor revision to MCA Section 948j (“Military judge of a military commission”):

These revisions would naturally require congressional approval, always an ambitious proposition in this highly partisan climate. Although we would not object to an executive order, we are hopeful that the legislative branch will accept our recommendation in the spirit with which it is offered: not to frustrate Congress’s will but to put jurists in place who can help advance it. Our proposal would also be subject to the approval of the Chief Justice of the United States or his designee. Again, we are optimistic that anyone who has risen to the Supreme Court would share our faith in the resolve of a U.S. District Judge to see the Guantánamo cases to a just conclusion.

We are aware, too, that federal judges, no matter how tenacious, would not be arriving at the naval base with magic wands. Much of their case-management authority—to compel testimony, to preclude evidence, to sanction counsel—flows from Article III of the U.S. Constitution, whereas the Military Commissions have been established under Article I. Several members of our task force have suggested that we propose additional powers for federal judges under the MCA, giving them tools more commensurate with an Article III court. While recognizing that such authority may be appropriate—and worthy of further study—we have agreed that it goes beyond the scope of this report. In any event, to the extent that federal judges would be operating within the confines of the MCA, they would not be of it. A federal judge, with the consent of that district’s Chief Judge, could agree to undertake the Military Commission assignment as his or her exclusive judicial duty. As a tenured officer of the court, outside the military’s chain of command, he or she could also independently commit to establishing chambers at Guantánamo for the duration of the case. Far from being susceptible to command influence, a federal judge would help inoculate the trial against potential meddling.

Precedent exists for appointing federal judges to preside over courts for special purposes abroad. President Eisenhower created one such court in Germany after World War II—the United States Court for Berlin—pursuant to his powers under Article II of the Constitution. After lying dormant for nearly a quarter-century, the court was convened in 1978 to try two East German nationals accused of hijacking a Polish jet. To preside over the case, U.S. v. Tiede, the State Department selected the Hon. Herbert J. Stern, a U.S. District Judge in New Jersey. To Judge Stern’s dismay, the same government that put him in charge of the case also wanted to tell him how it should turn out. In ruling that foreign nationals were entitled to a jury trial under the Constitution, he rebelled against State Department orders—a reaction, according to one commentator, likely due to his lifetime tenure and displeasure with receiving direction from Washington, which was “highly inconsistent with the self-image of federal judges.”

Although the United States Court for Berlin did not have jurisdiction over war crimes or enemy belligerents, as the Military Commissions in Guantánamo do, its establishment nevertheless supports the executive branch’s ability to recruit a federal judge to preside over proceedings abroad. It also shows constitutional support for allowing the federal judiciary to serve in a non-Article III court and apply an external body of law—there, it was German law; here, it could be the MCA. More importantly, even though he was serving outside the confines of Article III, Judge Stern retained the independence he was accustomed to on the U.S. District Court bench. Given the disruptions that have plagued the Guantánamo proceedings, the habitual exercise of autonomy that Judge Stern embodied could not help but speed these trials and ensure their fairness. Equipped with deep experience in CIPA procedures, a federal judge would also be better positioned to evaluate the millions of pieces of classified information that have thus far mired the cases in years-long discovery disputes.

Again, to say that U.S. District Judges are particularly suited for managing an unwieldy capital case involving allegations of extensive government torture is not to denigrate military judges. It is to highlight the time-tested expertise and makeup of the federal judiciary, whose capabilities we propose to supplement with the technological and procedural recommendations outlined in the next section. For those of us who are litigators, the most impressive judges we encounter are simply masters of “the art of judging,” courtroom deans with a talent for curbing lawyerly excess and encouraging consensus—if not by invoking the rules, then through sheer force of personality. A U.S. District Judge with those credentials would have an immediate impact on the pace at Guantánamo.

III. Closing the Gap

As much confidence as we have in the case-management and administrative capabilities of the federal judiciary, we recognize that the Guantánamo trials pose unique logistical and procedural challenges. To help close those gaps and facilitate management of the cases, we offer four additional recommendations. Like our proposed amendments to the MCA, these do not seek to dismantle or relocate the Military Commissions but to remove some of the obstacles impeding their headway. And like the appointment of federal judges, these tools will remain effective regardless of what ultimately becomes of the detention camp.

Technology. In a world that has never been more mobile and connected, there is no reason every pretrial motion involving a Guantánamo detainee should have to be heard in person. Even if a federal judge were stationed there, many other parties—lawyers, witnesses, interpreters—would still face the prospect of shuttling to and from the naval base. To permit expeditious resolution of pretrial matters, we propose that any judge appointed by the Convening Authority be authorized to utilize secure videoconferencing for the hearing of pretrial and discovery motions, pretrial and status conferences, and the like, and to order defendants or their counsel, as needed, to appear by closed videoconference as well. We would endorse an amendment to the MCA expressly granting that authority. We also support making videoconferencing technology available to defense counsel, whose ability to communicate confidentially with their clients—compromised at various points in these cases—is essential to promoting more efficient proceedings.

Given Guantánamo’s remoteness, establishing a secure transoceanic connection would have been a fantasy when the Military Commissions were initially formed. But in 2014, the U.S. Navy awarded a $31 million contract to a Texas firm, Xtera Communications, to install an underwater fiber-optic cable between Guantánamo and Florida. Scheduled to be active in February 2016, it should add significant bandwidth to the base, which is currently served by satellite, and permit for the kind of instantaneous global communications on which federal courts routinely rely.

Timeline. Although the MCA did away with an accused’s statutory right to a speedy trial under military law—a protection that some, though not all, of our task force members would like to see restored—we believe nonetheless that setting a trial date is critical to the effective management of these cases. Currently, Section 949e of the MCA (“Continuances”) makes no mention of scheduling orders, and instead provides broad authority to a Military Commission judge to “grant a continuance to any party for such time, and as often, as may appear to be just.” We recommend that Section 949e be amended to state explicitly that “the judge appointed by the Convening Authority shall schedule a trial date.” In our experience, federal judges treat their trial dates not as placeholders or pipe dreams but as strict, almost sacrosanct mileposts. Even if there is good cause to later continue that trial date, the simple act of setting one establishes goals for all parties and signals the judge’s commitment to guiding the case to a timely resolution. Moreover, the public, including victims and witnesses, has an interest in at least knowing that the Military Commission is proceeding along a firm schedule. We subscribe to the American Bar Association principles that policies and standards designed to achieve timely disposition of criminal cases should be established to, among other things, “minimiz[e] the length of the periods of anxiety for victims, witnesses and defendants, and their families” and “increas[e] public trust and confidence in the justice system.”

Victims. Every one of us who has traveled to Guantánamo as an observer has felt the anger, pain, and frustration of the victims’ families, some of whom have come to believe they will never in their lifetimes achieve legal finality given the pace of pretrial hearings and the specter of appeal. While we remain hopeful that our recommendations here will help bring relief to these families and restore their faith in the Military Commission process, we also believe there is a mechanism for incorporating their voices into the current proceedings.

One of our members, who served as a judicial law clerk to President and Judge Khalida Rachid Khan of the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, helped draft the 2011 judgment in Bizimungu, et al., a high-profile case against four Rwandan cabinet-level officials. By then, 17 years had elapsed since the genocide and 12 years since the indictments, an agonizing wait for the survivors and victims’ families. Recognizing that progress would be incremental, however, the tribunal had invited witnesses to testify during the discovery phase of the proceedings. Indeed, between 2003 and 2008, the trial court recorded testimony from 171 witnesses over the course of 399 days, preserving their recollections both for appeal and for history. Knowing that their testimony would survive for posterity comforted survivors and victims’ families and provided some with satisfaction that their stories were finally heard on an international stage. The same opportunity could be extended, even now, to families victimized by the 9/11 and USS Cole attacks. Rather than waiting years for the trials to begin, they could testify to the personal impact of these crimes during the pretrial phase. Under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 15(a)(1), when “exceptional circumstances and… the interests of justice” require it, courts have allowed videotaped deposition testimony to be admitted in criminal trials, provided counsel is present at the taping and the witness was subjected to cross-examination. Military Commission Rule 702 mirrors that standard. While some in our group have cautioned that managing victim testimony at this stage of the proceedings could impose a burden on the court, the majority of us remain optimistic that a full-time federal judge would devise an appropriate scheduling strategy. The victims have waited too long already. Initiating that process for surviving families now would give them a legal and public forum to memorialize their loss, and it would provide the Military Commission with a record of what these crimes inflicted for purposes of sentencing, if and when that occurs.

Openness. If a trial is to achieve the objective of maintaining public confidence in the administration of justice, it must remain open to the public—or as Justice Brennan once put it, “what transpires in a courtroom is public property.” While we are grateful that the Military Commissions have made accommodations for nongovernmental observers, as well as victims’ families and members of the media, we are concerned that the limits on documenting and transmitting the proceedings at Guantánamo have, at worst, bred suspicions of prejudice and, at a minimum, created conditions that have contributed to a general unawareness of and indifference toward these important proceedings. Assuming the appropriate security mechanisms remain in effect, we believe that all public Military Commission hearings—i.e., the legal machinery we have witnessed firsthand—should be made available for broadcast and Internet streaming. The Supreme Court began releasing same-week audio files of its hearings in 2010, and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in 2013 became the first federal appellate court to live-stream video of its proceedings. An audio and/or video feed from Guantánamo, whether on air or online, is essential to promoting public engagement, demystifying a process mired in misunderstanding, and articulating for the world how the Military Commissions advance American values and interests.

IV. Why We Care

In making these recommendations, our task force hopes to underscore the stakes of the Guantánamo trials—for our country and, on behalf of those of us who are lawyers, for our profession. We have deliberately focused our efforts on proposing narrow, pragmatic revisions to the existing legal mechanisms, a target that we think makes the best use of our collective experience. But neither our interest nor our concern ends there. We care about logistics and procedures because they shape the bigger questions: about legality and credibility, impartiality and transparency, public diplomacy and military principles.

Although as individuals we span the political spectrum, we all share the view that our country must do a better job of communicating, at home and abroad, what we are doing at Guantánamo and why. As recent events serve to remind us, the 9/11 and USS Cole attacks are unlikely to be the last time our government will feel compelled to take extraordinary legal action under emergency conditions. It is one thing to be a nation of laws in peacetime. It is how we respond in times of peril that will define what is meant by American justice.

The Pacific Council’s GTMO Task Force includes 18 members, most of whom have traveled to Guantánamo as official civilian observers. The views and opinions expressed here are solely each member’s own and do not reflect those of any company, organization, agency, or employer. ■

Richard B. Goetz, Co-Chair, is a partner at O’Melveny & Myers LLP and leads its mass torts practice. He sits on the Pacific Council Board of Directors and served as the Council’s inaugural Guantánamo observer. He wrote about that experience here.

Michelle M. Kezirian, Co-Chair, is a public interest lawyer.

Gordon Bava is a partner and the co-chairman of Manatt, Phelps & Phillips LLP.

Robert C. Bonner is a former U.S. Attorney, U.S. District Judge, Administrator of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, and Commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Lyn Boyd-Judson is Director of the Levan Institute for Humanities and Ethics at USC and Executive Director of the Oxford Consortium for Human Rights.

Joseph Calabrese is a partner at Latham & Watkins and chair of its Entertainment, Sports and Media Practice. He sits on the board and is past chair of the Constitutional Rights Foundation, an organization committed to civic education.

Mike Dwyer is Senior Vice President, Legal, at JAKKS Pacific and a retired U.S. Army JAG Corps officer.

Charles Gillig is CEO of RemitRight. He wrote about his Guantánamo experience here.

Jerrold D. Green is President and CEO of the Pacific Council on International Policy.

Marisa Hernández-Stern is a litigation associate with the civil rights firm Hadsell Stormer & Renick LLP, where she represents plaintiffs in employment class actions and other employment matters. She wrote about her Guantánamo experience here.

Perlette Jura is a partner at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher and co-chair of its Transnational Litigation Group. She wrote about her Guantánamo experience here.

Harry Leonhardt, Esq., is a veteran healthcare executive, general counsel, and chief compliance officer.

Alicia Miñana is a transactional attorney and the founding chair of the board of directors for the Learning Rights Law Center.

Robert C. O’Brien is a partner at Larson O’Brien LLP. He served as a U.S. Representative to the United Nations and as Co-chairman of the Department of State Public-Private Partnership for Justice Reform in Afghanistan. He wrote about his Guantánamo experience here.

Seepan Parseghian is a former associate at Snell & Wilmer and Vice Chair of the Pacific Council’s Eurasia Committee.

K. Jack Riley is Vice President and Director of the RAND National Security Research Division.

Harry Stang is a senior counsel and former partner at Bryan Cave.

Paul Tauber is a partner at Coblentz, Patch, Duffy & Bass LLP.

Staff

Dru Brenner-Beck, a retired Army JAG Corps officer, contributed research assistance.

Tristan Bufete, an O’Melveny & Myers associate, contributed research assistance.

Jesse Katz, a journalist and author, provided drafting and editing assistance.

Kaveh Farzad, the Pacific Council’s Communications Officer, Melissa Lockhart Fortner, the Pacific Council’s Vice President of Communications, and Ashley McKenzie, the Pacific Council’s Trips Officer, provided additional staff support.

This report was published in February 2016.

The Los Angeles-based Pacific Council is an independent, nonpartisan organization committed to enhancing the West Coast’s impact on global issues and policy. Since 1995, the Pacific Council has hosted discussion events on issues of global importance, convened task forces and working groups to address pressing policy challenges, and built a network of globally-minded members across the West Coast and the world.

Visit us at www.pacificcouncil.org.