Letter from Editor

ZEKE: Vol. 2/No. 1, Spring 2016

Dear ZEKE readers:

As I write this letter before sending this third issue of ZEKE off to the printer, I am reflecting on what we have accomplished in our first year of publishing and want to thank all the photographers, writers, subscribers, and others who have helped to make this possible. Just the fact that we made it into our second year is an accomplishment! This is also the first issue available by subscription. We also are now working with Ubiquity Distributors to help us get ZEKE into bookstores and magazine stands.

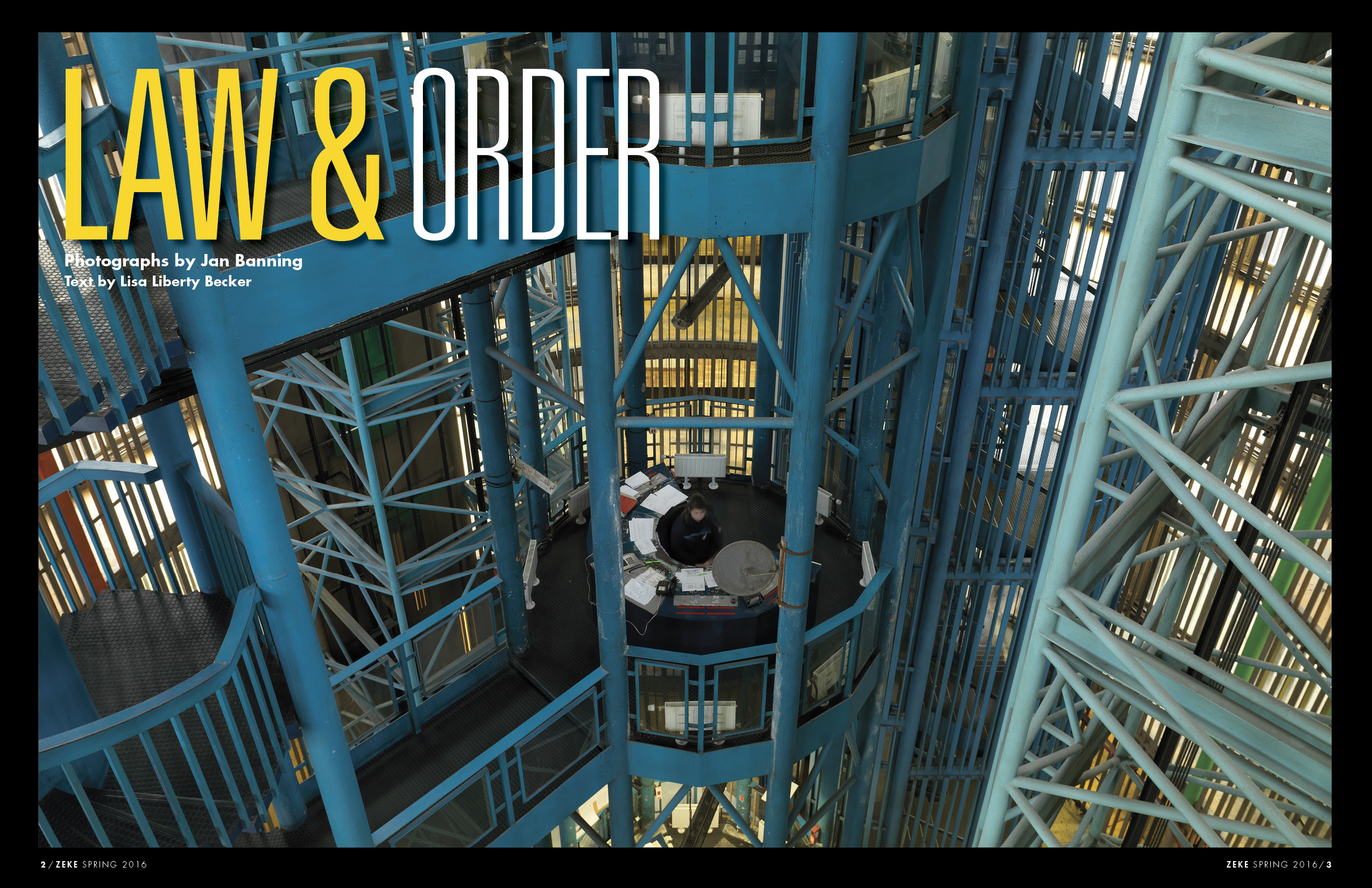

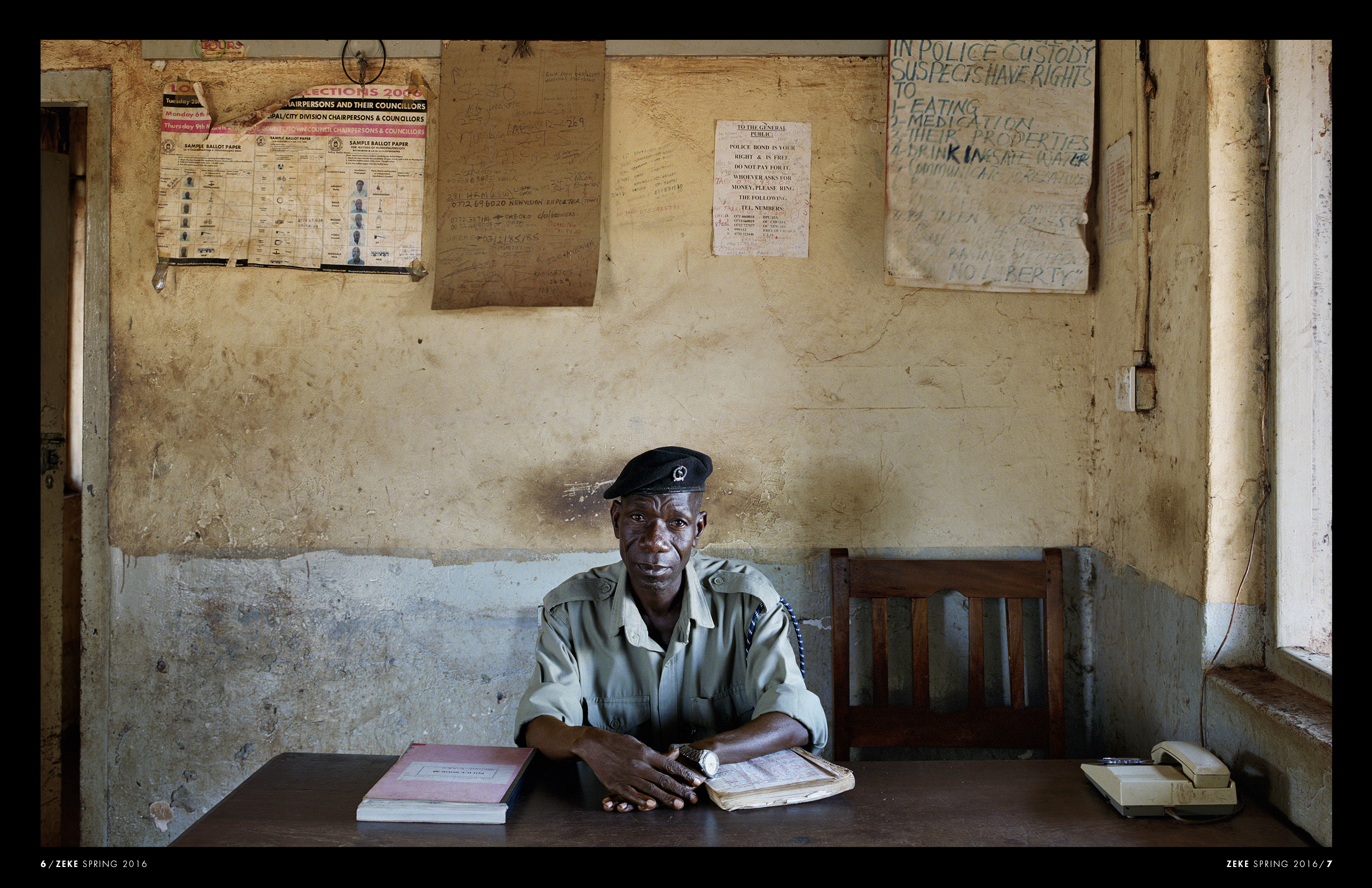

The first article in this issue of ZEKE, Law & Order, features the work of Jan Banning. Jan was the winner of SDN’s last call for entries. Elizabeth Krist, National Geographic photo editor and a juror for the call for entries, eloquently sums up Jan’s work:

The range of coverage is impressive–not only the physical contrast in facilities from one continent to another, but portraits of the incarcerated and administrators alike, both seen with directness and humanity. Banning gives us a revealing view of issues that occasionally surface in the news but are seldom seen so intimately, and forces us to ask what the impact of being a prisoner will have on these lives.

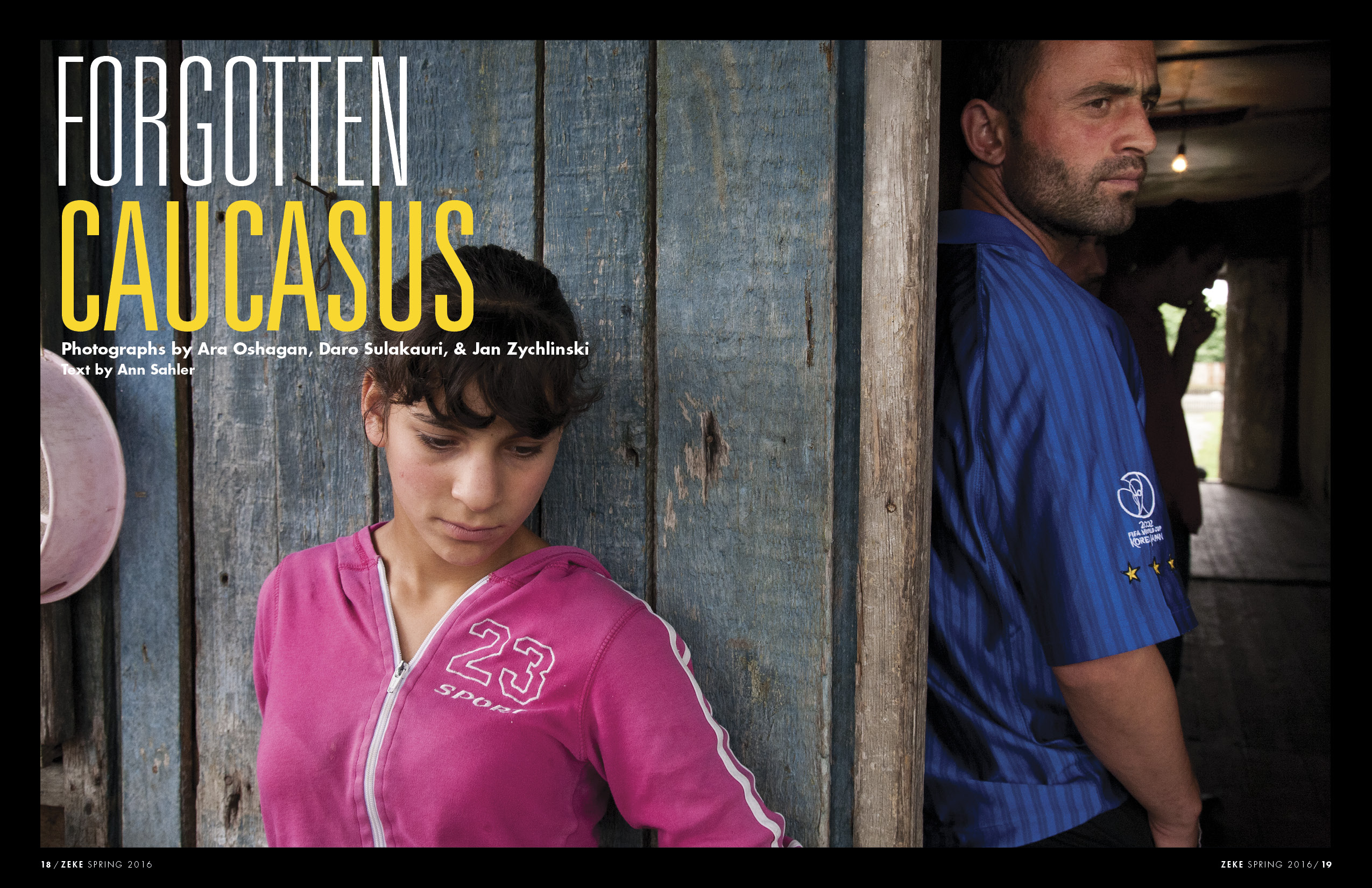

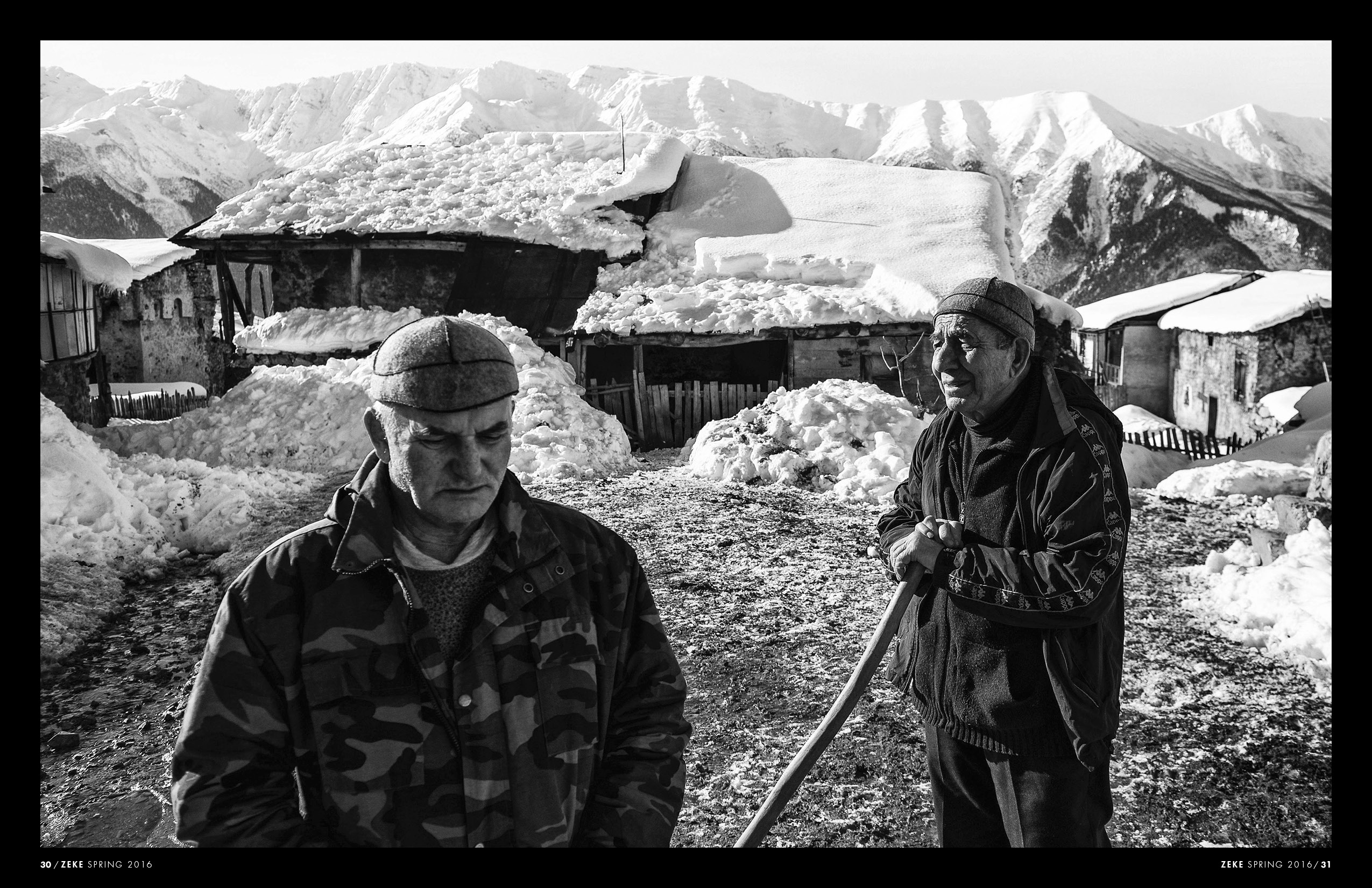

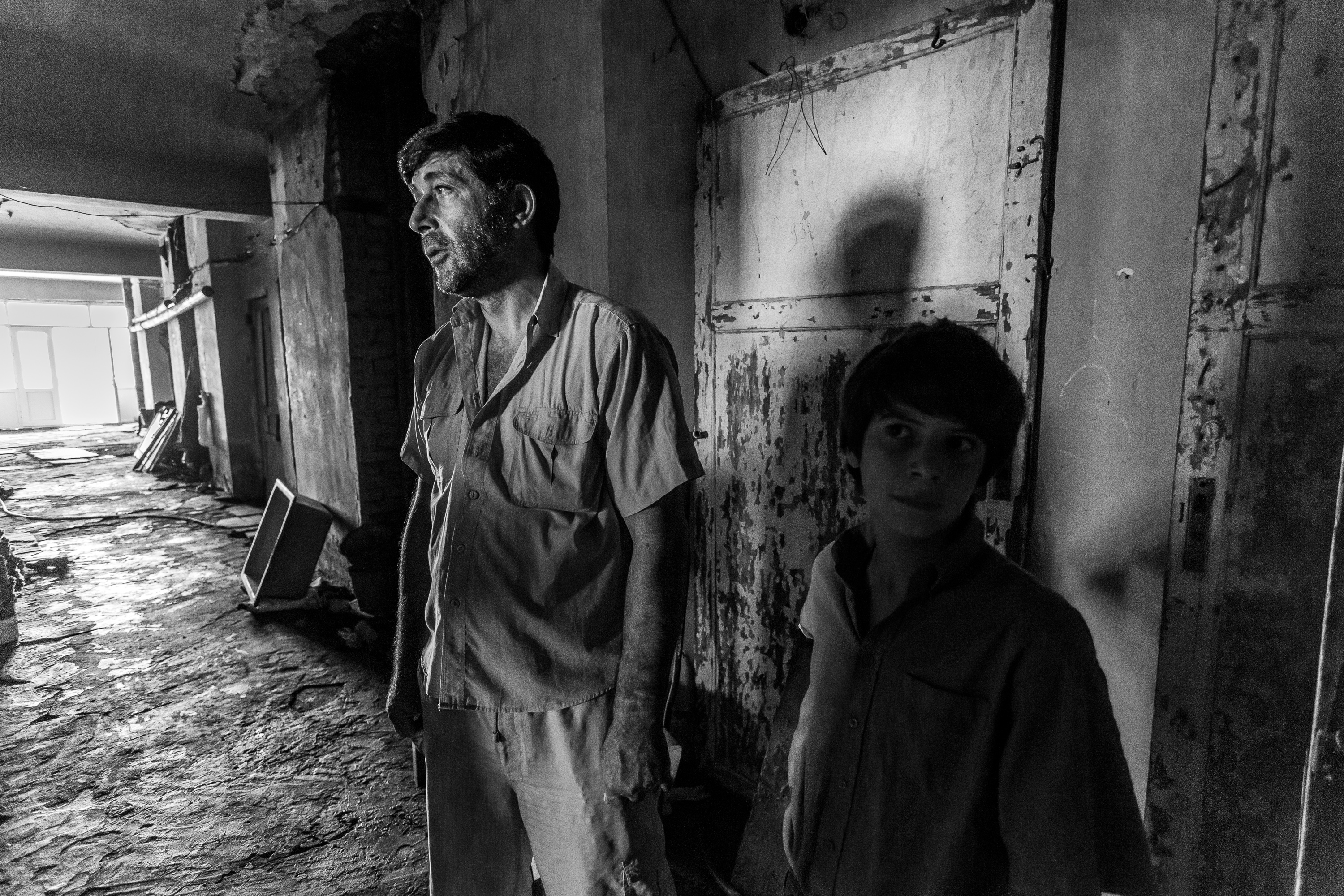

Our second feature, Forgotten Caucasus, explores three countries created by the fall of the Soviet Union: Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. We have received many powerful exhibits on the SDN website from this part of the world and we felt that such an important and under-reported region deserved our greater attention. A week before going to press, conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh (an Armenian enclave within Azerbaijan) flared up killing dozens of soldiers and civilians, reminding us that these “frozen zones” remain tinder boxes of conflict between world super powers.

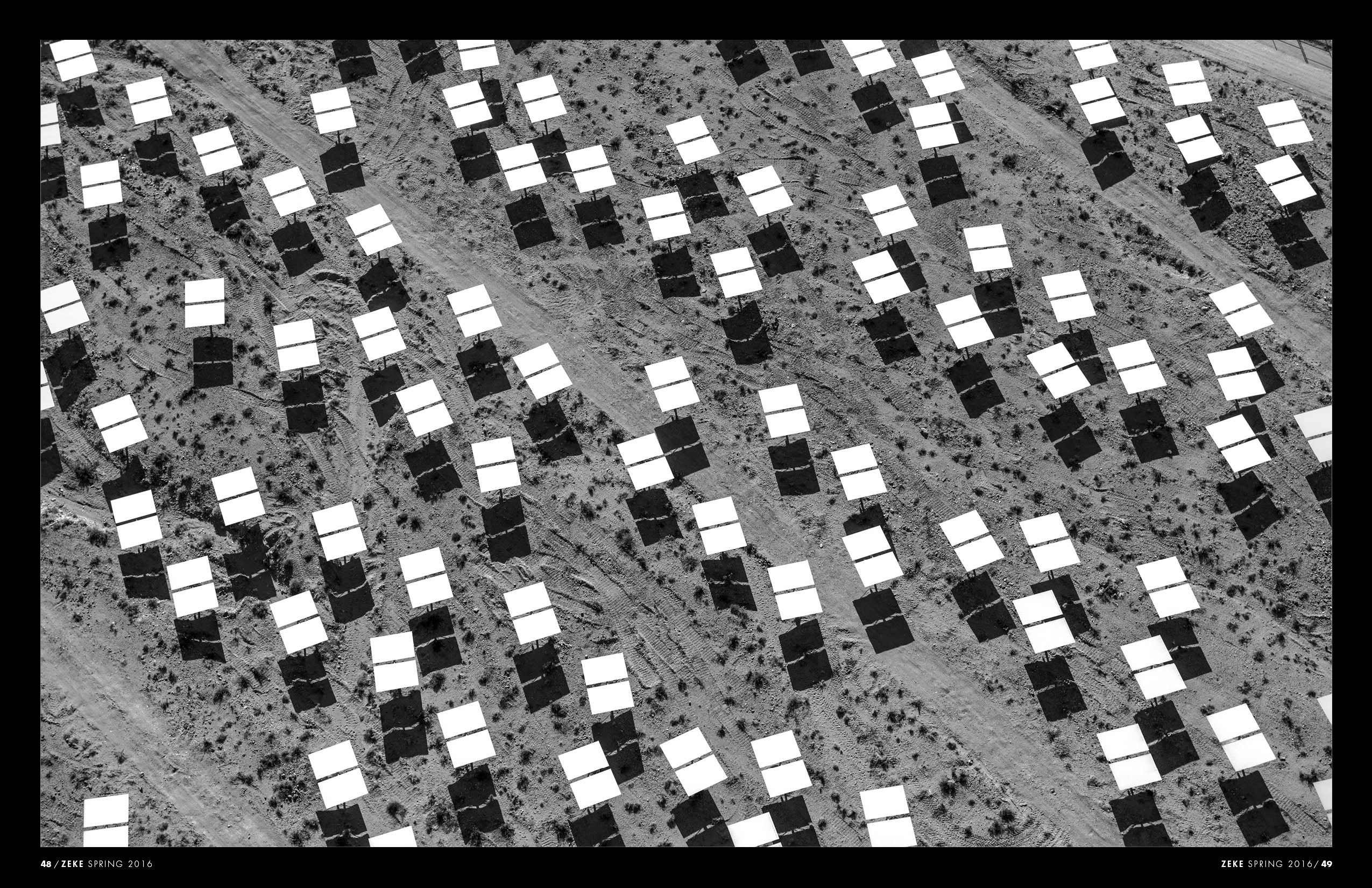

The third feature, Climate Change, explores the existential threat to human civilization. The photos by Jordi Pizarro and Probal Rashid present the human face of climate change by showing us communities in India and Bangladesh that are losing their homes and the land beneath them due to rising sea levels. The work by Jamey Stillings presents stunning black and white photos of the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System in the Mohave Desert—the world’s largest concentrated solar thermal power plant. This facility will contribute to diminishing the production of heat-trapping greenhouse gasses.

We also have an interview with the Russian photojournalist Sergey Ponomarev, an article on the innovative social media project of Bangladeshi photographer Ismail Ferdous, and other work of trending photographers on SDN.

Glenn RugaExecutive Editor

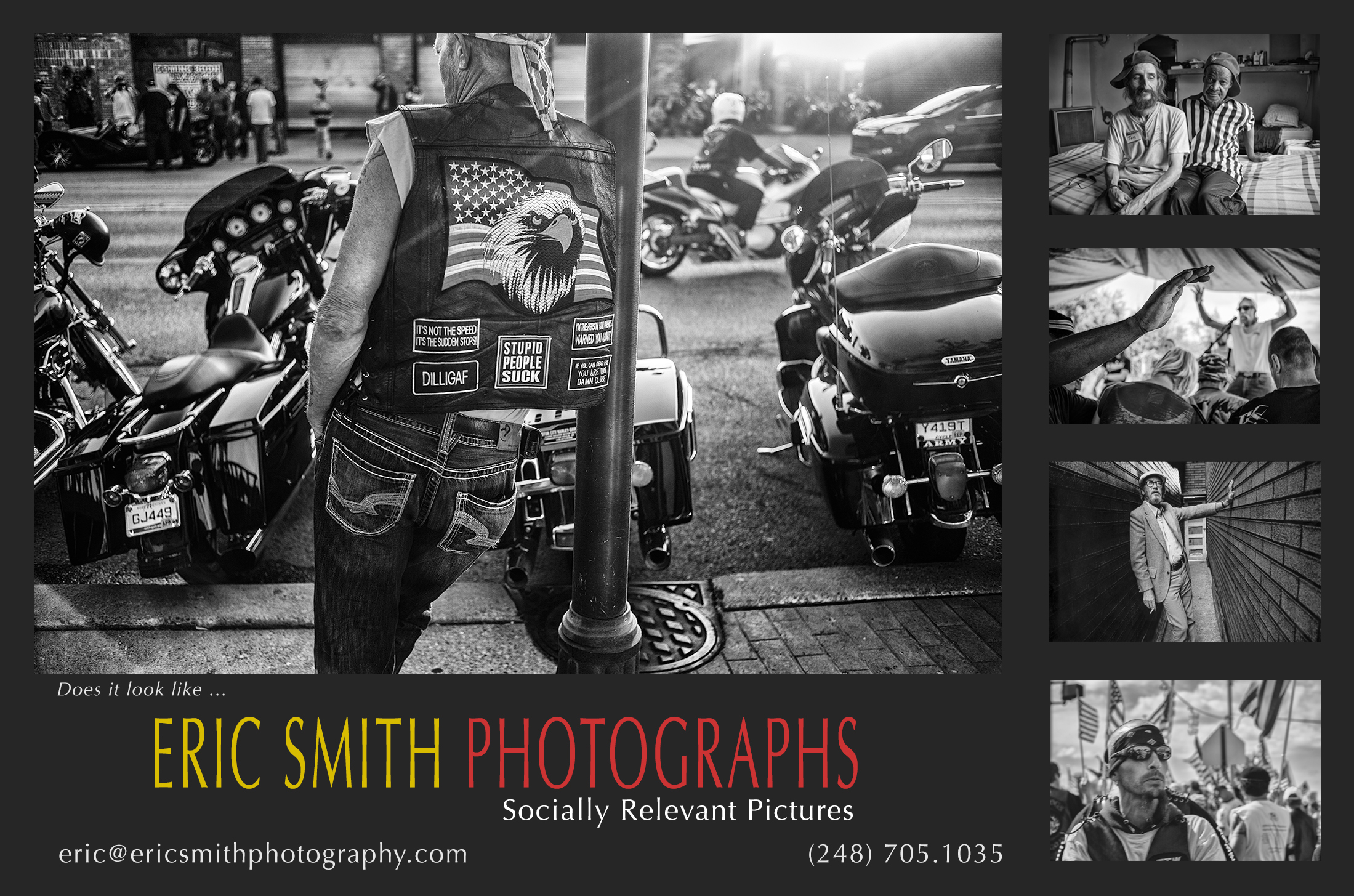

Law & Order: Photo Gallery

Photographs by Jan Banning.

Worldwide, 144 out of every 100,000 people are in prison. In the United States, that number jumps to 698 per 100,000. Though prison populations and the conditions of those prisons vary from country to country, the world prison system has many common problems, including prisoner mistreatment, overcrowding, gangs, unsanitary conditions, sexual assault, and rampant communicable diseases. ZEKE featured photographer Jan Banning became interested in criminal justice after finishing a project on bureaucracy; the photos in his book Bureaucratics examine the state civil administrations in eight countries. Turning his focus to the judicial pillar of society, he decided to focus on prison systems worldwide. Banning visited prisons in Colombia, France, Uganda, and the United States, discovering visual differences in the overall affect of the prisons. The photographs on the following pages, which also appear in his recently-released book Law & Order, reflect the daily realities of police, criminal justice officials, the courts, guards, prisoners, and often-hidden prison conditions. Banning leaves it up to us to continue the debate on prison reform.

Jan Banning was the winner of the Social Documentary Network’s 2016 Call for Entries on Visual Stories Exploring Global Themes. Click here to order his newest book, Law & Order: The World of Criminal Justice.

Criminal Justice: Article

Text by Lisa Liberty Becker

To be “tough on crime” is more than just an expression; the United States and other countries have enforced such policies for more than two decades. Punishment as a primary response to crime, often the only response, has created a world with over 10.35 million people in prisons, according to the latest World Prison Population List report, released in February by the Institute for Criminal Policy Research (ICPR) at Birkbeck, University of London. While conditions in those prisons vary from country to country, the debate remains: what’s the purpose of imprisonment — retribution or rehabilitation?

The United States leads the way in overall number of prisoners with a staggering 2.2 million, followed by China (1.65 million), the Russian Federation (640,000), Brazil (607,000), and India (418,000).

Punishment as a primary response to crime, often the only response, has created a world with over 10.35 million people in prisons.

—World Prison Population List

Researchers at the ICPR, have been collecting data on prison populations by country since 1997. The ICPR’s World Prison Brief database now includes such statistics from all but three countries in the entire world (Eritrea, North Korea and Somalia).

According to ICPR Research Fellow Helen Fair, governments use the World Prison Brief to see how they compare to the rest of the world. Take, for example, Kazakhstan, which in 2013 set a goal of getting out of the top 50 in terms of highest prison population rates. “[Kazakhstan] sends us regular updates on their prison population numbers so we can update the World Prison Brief, and they have now succeeded in their goal,” says Fair, who helps maintain the World Prison Brief database. The prison population numbers for Kazakhstan keep falling, and the country has gotten itself out of that top 50. “The big international organizations like Amnesty International also use it in their campaign work,” Fair says. “We are supplying the factual information that allows other people to apply that and be able to see the context.”

Given that the global prison population has risen by 20 percent since 2000 — more than the 18 percent increase in the world population during that same time period — it appears that the system as a whole still seeks to make people convicted of crimes pay for their offenses by locking them in prison. America’s prison population rate of 698 is second only to Seychelles, which has a mere 97,000 residents. While the number of US prisoners has declined slightly since 2010, that doesn’t detract from the fact that America has imprisoned nearly 2 million people per year since 2000.

“We are a very punitive system and very harsh in our judgments,” says Andrew Cohen, commentary editor at The Marshall Project, a nonprofit think tank focused on the American criminal justice system. Cohen, also a legal analyst for 60 Minutes and CBS Radio News and a fellow at New York’s Brennan Center for Justice, has reflected on everything from prison reform in Georgia, to mass incarceration, to the heroin epidemic. “Politics also play a part,” Cohen adds. “It’s easier for politicians to stand up and say, ‘We need harsher sentences.’ It’s harder for them to say, ‘We need to be more lenient with our sentencing.’“

Baz Dreisinger visited disparate countries to tell a story of prisons in her new book Incarceration Nations. Dreisinger, who teaches at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice at the City University of New York (CUNY), intersperses reflections on prison conditions in the United States with what she saw first-hand in countries such as Uganda, Singapore, and Norway. “In all countries, I found that prisons were … echoes of the society that created them,” she writes in her book. This can be seen everywhere from the stainless-steel bar-laden institutional correctional facilities in the United States to the exemplary Halden in Norway, a prison with zero bars, a rock climbing wall, and private rooms with bathrooms and flat screen televisions.

In the current mass incarceration system, there is little evidence that incarceration actually changes behavior.

In the current mass incarceration system, there is little evidence that incarceration actually changes behavior. According to a 2014 Bureau of Justice Statistics report, over 75 percent of prisoners released in 30 US states in 2005 were arrested for a new crime within five years. Data like this is not perfect, since it does not separate violent and nonviolent crimes, nor does it mention the number of people who were actually convicted of those crimes. However, it does get government officials and other policymakers thinking about humane treatment of prisoners and alternatives to prison. “Harsh punishments and prison terms aren’t going to solve anything,” says ZEKE featured photographer Jan Banning. “You are going to have a few people who are so dangerous for society that you probably have to lock them up forever. Other than that, I think we need to focus more on the correction aspect, improving the situation and living conditions in prisons.”

When it comes to improving the system, organizations such as Penal Reform International and the American Coalition for Criminal Justice Reform are trying to change the tide, as are individuals. Dreisinger also created P2CP, the Prison-to-College Pipeline, which brings college courses to prisoners in New York State. “I’m very interested in the value of education, and the prison system is sorely lacking in rehabilitative programs,” she says. This program, now in its fifth year, also guarantees participants a spot in the CUNY system upon release. Dreisinger adds that when she was researching Incarceration Nations, she was surprised to find like minds. “There’s a global coalition of people who really see that the system is broken in a number of ways.”

There is a financial cost to locking up a lot of people, but there’s also a wider social cost, the effects on society, on families.

—Helen Fair, Institute for Criminal Policy Research

With prison costs in the United States alone at $80 billion per year, and overcrowding problems around the world, it is clear that the current system is not sustainable in terms of finances or ethics. “There is a financial cost to locking up a lot of people, but there’s also a wider social cost, the effects on society, on families,” says ICPR’s Fair. “Those are the kinds of things we will be looking at, to see where progress is made over the next five years or so. We want to see how countries will go about doing that, to see if there really is a way to make changes.”

On March 30 of this year, President Obama commuted the sentences of 61 drug offenders in federal prisons, one-third of them serving life sentences. The Foreign Prison Improvement Act of 2013, which would hold governments around the world accountable for maintaining humane prison conditions, was introduced by Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy but died in Congress. Although each country has its own areas for improvement, there may be hope yet for a less punitive and more rehabilitative system overall.

For more information

Forgotten Caucasus: Photo Gallery

Photographs by Ara Oshagan, Daro Sulakauri, Jan Zychlinski

Ara Oshagan, an Armenian photographer born in Lebanon and now living in America, is a child of the Diaspora. He takes the viewer on a personal journey through Nagorno-Karabakh, the Armenian homeland in which he has never lived. His photo essay, conducted with his father, a famous Armenian writer, explores the ambiguity of belonging and not belonging, the history of Armenia and its people, and Ara’s relationship to the country.

The tradition of early marriages in Georgia provides Georgian photographer Daro Sulakauri the backdrop for her powerful images. The custom is illegal, yet Georgia has one of the highest rates in Europe of marriages below the age of 18. These weddings occur predominately in the Kvemo Kartli and Ajara regions among religious and ethnic minorities. Daro’s photographs generate a discussion around the issue of early marriages, providing insight to the outsider.

Jan Zychlinski, a photographer based in Switzerland, travelled from September 2014 to February 2015 around the South Caucasus to document the inhumane consequences of armed conflict after the collapse of the Soviet Union more than 20 years ago. He skillfully documents the internally displaced people who left their homes to seek shelter as refugees in camps, collective centers or newly built settlements far removed from the rest of society — many of them still living under these conditions.

Forgotten Caucasus: Article

Text by Anne Sahler

While topics like the Syrian refugee crisis, Islamic State-sponsored terrorism, and the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Palestinians dominate the news, there is another region facing tremendous challenges: The South Caucasus. A pivotal junction located between Russia, Turkey, and Iran, it straddles the periphery of the Middle East encased between the shores of the Black and the Caspian Seas and crisscrossed by the Caucasus mountains.

With a millennia-long history, the Caucasus is one of the most diverse regions imaginable. Nowhere else can you find such a richness of religious, ethnic, cultural, linguistic and geopolitical identities that feed an endless manifold of conflicts. The region has historically been an area of war and contention for centuries. Ruled by the Persian, Ottoman and Russian Empires at the beginning of the 19th century, each left behind their own political and cultural legacy. The daunting web of challenges which lies ahead for the South Caucasus is no less vexing than the complex history it strives to leave behind.

A tinderbox of conflicts and challenges

It was just after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991 that the states of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia in the South Caucasus became not only independent nations, but also areas of renewed conflict. Violent ethno-territorial strife in Nagorno-Karabakh, South Ossetia and Abkhazia divided the region providing a tinderbox of instability and worsening challenges. The clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh, coupled with the Russian occupation of two enclaves in Georgia — Abkhazia on the Black Sea and South Ossetia — have resulted in massive upheaval and the suffering of local populations. Both conflicts resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands, as well as trauma, insecurity, displacement and seemingly insurmountable challenges for those who survived.

Relations between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagarno-Karabakh remain tense. Populated by ethnic Armenians but lying within Azerbaijan, the conflict that began in 1988 reached its peak between 1992 and 1994, leaving at least 25,000 people dead and more than a million displaced from their homes.

The war between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagarno-Karabakh between 1988 and 1994 left at least 25,000 people dead and more than a million people displaced from their homes.

Tension lingers and the risk of a re-escalation of hostilities in this landlocked region of divided societies remains a very real possibility as the latest developments in Nagorno-Karabakh show. Dozens of people have been killed this April, including a young boy, in the worst fighting between Armenia and Azerbaijan since the 1994 ceasefire. As of April 13, when ZEKE went to press, a ceasefire has been announced ending four days of heavy fighting. Still, the danger that the often-referred to “frozen conflict” may escalate into a full-blown war remains an ever present threat.

Abkhazia broke away from Georgia in 1992 and the 13 months-long war that followed resulted in the deaths of more than 12,000 and the displacement of nearly a quarter million ethnic Georgian refugees who fled their homes in Abkhazia. What followed in 2008 was a five-day war, involving Russian and Georgian forces in South Ossetia. The Russian Federation, recognizing Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent nations, stationed military forces in the region exposing people living in frontline areas to future escalations of conflict.

The challenges do not end there. Humanitarian concerns bedevil the region including child marriages, meager living conditions of the rural populations, and internally displaced persons. Refugees who left their homes as a consequence of the armed conflicts after the collapse of the Soviet Union are further distressed and hampered by the general lack of basic human rights. “Freedom” in the democratic Western European sense is not applicable in Georgia, Azerbaijan or Armenia.

“The South Caucasus is a quite complex region with differing developments in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia,” Giorgi Kanashvili, Executive Director of the Caucasian House in Tbilisi, Georgia, says. “In a nutshell, there is a tangible process in Georgia regarding democratization. People are quite optimistic and have trust in the future. The situation in Azerbaijan, on the contrary, has worsened every year concerning the growing authoritarianism. Although we don’t observe the same type of regress in Armenia, there are also negative tendencies. And the Georgian breakaway regions? In South Ossetia it is very difficult to talk about any type of democracy, as the situation is quite depressing and we can actually observe an ongoing depopulation of this region,” Giorgi explains further. “But in Abkhazia, though we cannot talk about democracy, we can talk about a certain form of ethnocracy. People there are more optimistic than in South Ossetia for sure.”

South Caucasus role on the global political stage

The EU, Russia, Turkey and the US all have varied interests in the South Caucasus countries.The European Union and the United States interests in the South Caucasus are similar — stability, development, trade, and energy as well as democracy and human rights. Russia’s interest lies in maintaining its influence, manageable conflicts, and energy infrastructure. Turkey, for its part, is focused on the interests of energy and trade, Nagorno-Karabakh and the subsequent relations with Azerbaijan and Armenia, as well as cultural and ethnic ties to the region. As all of these countries maintain close ties with the Caucasus, they are understandably concerned with its instability. Recently however attention has turned to the issues posed by the Arab Spring uprisings, the rise of the Islamic State and the unfolding Syrian refugee crisis, which has led the focus away from an engagement in the South Caucasus.

Additionally, diplomatic initiatives of the late 2000s that were supposed to vitalize regional development have broken down thereby raising failed expectations for the people of the South Caucasus and providing fodder for further disputes and challenges. The instability of the South Caucasus due to geopolitical rivalries and external partners and the kaleidoscope of fractious relationships between Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia undoubtedly provide negative influence on the economic development, governance and security of the entire region.

Challenges as opportunities

One of the main questions the South Caucasus now faces is how social well-being and economic growth on a sustainable level can be achieved in such an explosive mix of challenges given the lack of a common identity. In the end there won’t be stability in the interlinked Caucasus region if there is no cultivated culture of tolerance and recognition for the ethnic diversity the region is characterized by. Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia face many challenges — yet every challenge provides an opportunity for reforms and positive steps forward.

For more information:

Caucasian House CASCADE Conciliation Resources Freedom House Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

Climate Change: Photo Gallery

Photographs by Jordi Pizarro, Probal Rashid, Jamey Stilllings.

In October 2012, when Superstorm Sandy struck the eastern United States, the world watched in awe as New York City and the surrounding area was forced to confront the realities of climate change head on. By the time the hurricane passed, New York’s subway system had filled with seawater, as had Manhattan’s streets and tunnels, thousands of homes were damaged and most residents went days without electricity. Ultimately, the storm’s final economic toll on New York reached nearly $18 billion.

New York recovered, but worlds away, inhabitants of islands continue to face these troubling realities every day. According to a 2013 United Nations report, the world could see a three-to-six-foot rise in sea level by 2100 due to the melting of Earth’s ice caps, a prospect that would mean an increase in natural disasters like cyclones, flooding, erosion and drought. For some, this will mean forced migration further inland, away from coastlines. For many, it will mean abandonment of a way of life that is tied to their homeland, of a shared history, culture and tradition.

In this edition of ZEKE Magazine, three photographers confront the truths of climate change head on: Jordi Pizarro, an independent photographer based in New Delhi, captured life on a sinking island in the Bay of Bengal; Probal Rashid, a photojournalist from Bangladesh, documented the lands ravaged by the rising sea in Bangladesh; and Jamey Stillings, a photographer from Santa Fe, New Mexico, uncovered the global impact of a large-scale renewable energy project in the United States.

Climate Change: Article

Text by Margaret Quackenbush

When United States Secretary of State John Kerry addressed a delegation of foreign ministers gathered in Alaska last August for the Conference on Global Leadership in the Arctic, the world was in the midst of an historic refugee crisis. Thousands of Syrians were fleeing their homeland for Europe, unleashing a crisis the world has yet to fully address. For Kerry, it was a reminder of how ill-prepared we are to manage an emergency of that magnitude, and a warning that the possibility of an even larger humanitarian crisis caused by the worst effects of climate change is looming.

“You think migration is a challenge to Europe today because of extremism, wait until you see what happens when there’s an absence of water, an absence of food, or one tribe fighting against another for mere survival.”

—John KerryU.S. Secretary of State

He called them “climate refugees:” people forced to flee from the cascading effects of global warming -— sea level rise and the flooding, erosion, landslides, desalination of farmlands, drought and famine that could ensue. And, with urgency, he assured the delegation that the seismic effects of climate change have already been set in motion:

“The bottom line is that climate is not a distant threat for our children and their children to worry about. It is now.”

Climate Change is Inevitable

Today, global warming is melting glaciers at a rate three times faster than in the last century, and as they melt, the level of sea rises. In addition, scientists can see that Earth’s permafrost — the layer of soil that remains frozen throughout the year — is also melting, releasing methane into the atmosphere, a greenhouse gas that is significantly more damaging than carbon dioxide. As these gases increase, temperatures will likely go up over land surfaces; in fact, 2015 was earth’s hottest year on record, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And as temperatures rise, the intensity of storms and the instances of drought in between storms could increase.

Climate change is inevitable. Henry Lee, director of the environment and natural resources program at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, said researchers agree that the changing climate cannot be reversed, only its repercussions can be mitigated.

“We’re already on the path. We’re already on the slippery slope,” he said. “What we can do is reduce the severity, but we can’t stop it.”

The Migration Policy Institute predicts that more than 200 million people could be displaced by climate change by 2050.

Humanity will not have to wait another 30 years to see the effects of climate change–it’s happening right now. On the Marshall Islands in the South Pacific and the Sundarban Islands in the Bay of Bengal, life is literally vanishing. The Marshalls, which lie just six feet above sea level, could disappear by the end of the century, forcing their 70,000 inhabitants to seek refuge elsewhere (likely in the United States, where the Marshalls have an agreement allowing free emigration). And in the past 30 years, four of the Sundarban islands have sunk into the sea, and 18 million residents in nearby Bangladesh are in danger of being displaced by rising water and increasingly intense cyclones.

For developing nations, the problems will be even more harshly felt, according to Paul Kirshen, a professor of climate adaptation at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

“They just don’t have the institutions or the wealth to deal with these problems. So the impact there is going to be worse,” he said.

What does this mean on the individual level? It could mean human migration on an unprecedented scale.

The Migration Policy Institute predicts that more than 200 million people could be displaced by climate change by 2050. By that time, some scientists predict the world will see a sea level rise of about three feet, a reality that will cause chronic flooding, higher tides and bigger storm surges, and force millions of people away from coastlines and out of major cities like New York, Miami, London, Venice, Sydney and Shanghai.

Rethinking Urban Design

Now, climate change advocates are pushing to both reduce emissions and gain buy-in from the rest of the world. It is no easy task, but today these advocates have more political backing than ever. At a critical UN conference in Paris late last year, 195 nations reached an accord that, for the first time, committed nearly every country to lowering greenhouse gas emissions (previous climate change accords exempt developing nations like China and India, two of the largest greenhouse gas emitters). Moreover, the accord pledged to prevent global temperatures from rising two degrees Celsius, the point at which most scientists agree will avoid the most disastrous effects of climate change.

That does not mean climate change can be stopped altogether, but at least the worst of it can be avoided. In the meantime, most advocates and researchers are focusing on how to adapt and remain resilient in the face of the changing climate. That means creating incentives for renewable energies like wind and solar power, reducing carbon footprint by using fewer fossil fuels and developing new farming practices to alleviate the risk to the food supply.

The Migration Policy Institute predicts that more than 200 million people could be displaced by climate change by 2050.

Kirshen argues that rethinking urban design is key to how we accommodate our rising seas. In the United States, millions of people live in areas on the coasts that are vulnerable to climate change-related flooding. Cities like Boston and New York will need to divert resources towards flood proofing buildings, designing infrastructure that can withstand spates of seawater and building stronger seawalls.

“The idea is you live with the flooding. You have floating houses and design urban areas to be periodically flooded,” he said.

For Henry Lee, this will be an enormous undertaking. It’s difficult to convince cities to take action to alleviate a future pain, especially when there are so many more immediate pains to deal with daily, Lee explained.

“I don’t have a secret sauce as to how we should adapt, and will adapt, and how things will change,” he said.

It’s an overwhelming task, but a hugely important one, Lee said. And it’s one we all must commit to if we’re going to survive the next 100 years and beyond.

For more information

The United Nations website on sustainable development Climate Action Knowledge Exchange weADAPT

What’s Hot

Margarita Mavromichalis, Brian Driscoll, David Horton, Sami Siva

Of the hundreds of exhibits submitted to SDN each year, these four stand out as exemplary and deserving further attention.

Interview with Sergey Ponomarev

by Caterina Clerici

Sergey Ponomarev is best known for his photojournalism work depicting Russian daily life and culture as well as news images from wars and conflicts in the Middle East including Syria, Gaza, Lebanon, Egypt and Libya. Sergey has won many international and domestic photography awards. Most recently, he won first place in the General News category at the World Press Photo contest for his work on the European refugee crisis and he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2015. From 2003 until 2012 Sergey, was a staff photographer at The Associated Press. He is now a freelance photographer and works frequently for The New York Times.

__________________________

Caterina Clerici: How did you get started in your career as a photojournalist?

Sergey Ponomarev: I was always interested in journalism, that’s my family tradition. My father was a journalist, he was a foreign correspondent for a Soviet news agency. Somehow later I discovered I’d rather use visual language than the narrative text language. First, I could express myself better with images and when I started working with international media, I found that they could be understood by anyone in the world. Visual storytelling could be understood internationally without any translation.

CC: You started working with AP in Russia in 2003 and then you went freelance in 2012. How was the transition between getting assignments from a wire to pitching stories as a freelance journalist?

SP: That was one of the reasons why I quit the wire agency. I’m not interested in fashion or event photography, because I feel like I am sent there and I just press the button, I don’t even edit the images. There is no challenge.

Going freelance was a tough decision. In the modern world it’s very hard to compete and find your way. Also freelancers have to take care of their equipment and computers, whereas agency photographers are provided with everything. After eight years, trying to find my own way to become a freelance journalist was a big challenge for me. In some ways it’s kind of like having a business, it’s not a job. You have to find ideas, you have to find those who will be interested and you have to sell your own product.

CC: How did you carve your niche in the market? Is it geographical (Russia and Ukraine) or thematic, according to your topics of interest such as conflict photography and migration? How did your past experience at AP shape your brand as an independent photojournalist?

SP: There are several options to develop oneself as a freelance photographer. You can be based in a region. So for example, I’m a Russian photographer and I will mainly shoot stories out of Russia, Ukraine and neighboring countries. But I was always interested in the Middle East. If you work in the Middle East you face more conflict. If you work in Africa you face more human rights violations. So this is why I had to develop my conflict expertise, because in the Middle East there are always clashes and war.

When I started my career, I proposed some stories out of Russia, some environmental stories, and some political, but my career really kicked off more successfully after I went to Syria. I came with a unique story on how the closed regime of Assad lived and the effects of war on ordinary people. And this was something very fresh. Editors at The New York Times became interested and now I work a lot with this newspaper. I proposed a story about Assad’s Syria to the Visa pour l’image festival in Perpignan, and I had a very fresh and unique perspective.

CC: How did your previous experiences covering conflict shape the way you approached Ukraine?

SP: Ukraine is a pain in the ass for me. I would say it like that. For a photographer and a journalist it’s very important to stay independent from the context. Even if you’re going to cover the ‘wrong’ side of the conflict, you’re still going to judge what people do and what people claim independently, or at least you’re pretending to do that. With Ukraine, which is a neighboring or brother country [to Russia], it was really hard to stay independent. By judging it independently, and by being in and out of some areas, I’ve been losing friends and I’ve been losing my understanding of what’s going on because both sides of the conflict were just overwhelmed with propaganda. The lie was from both sides, even at the beginning of this conflict. The main fights and the main battles were happening around the TV towers, so those who control the TV towers control the region. Speaking on the ground with the people about the annexation of Crimea as a reunion with Russia could be difficult because people would think differently, and their thoughts were shaped by TV propaganda.

CC: You tend to go for very dramatic moments but you mange to depict human tragedy with a lot of dignity. How do you approach that — and is there a difference between working in a more familiar place like Ukraine versus a country that you don’t know?

SP: I come from an understanding that photographs right now cannot stop war. Imagine Nick Ut’s image of the girl running from napalm — the one that won the Pulitzer Prize. I’m sure that nowadays this image on the majority of news sites would be shown with a warning at first, that you’re about to see graphic content and that you should be aware of that. So that image in 2016 will not shock people as it shocked them in the 1960s. And that shock made them protest against war and force decision makers to stop it. And when I’m on the ground and I see human flesh or something graphic I feel like I’d better turn around and photograph live people who are seeing that, rather than photographing dead bodies. And the emotions of those who are still alive, in my opinion, will be more powerful.

CC: You’re talking about graphic content warnings and yet how to still surprise readers in a time where we seem to have become accustomed to images of war. What were your thoughts on the photo of Alan Kurdi, the drowned Syrian boy whose image shocked the entire world and stands pretty much at the other end of the spectrum from how you have documented the refugee crisis?

SP: First of all, I haven’t seen any drowned bodies in those five months that I documented the refugee crisis. I was asked about that when there was a discussion in the French media and I was at Perpignan. Most newspapers published this photo on the front pages or inside, except the French media, who decided not to show it to their audiences. I was against that, because I understand that modern rules don’t allow photography to be shocking, advertisers don’t want to see their ads next to shocking pictures. We’re just overwhelmed with visual information and TV screens and advertising screens all around us. But the medium of photojournalism is not just a regular digital information tool. It’s not that photojournalists are like vultures. They’re trying to find the most shocking, the ugliest stories happening in our world and this is not a bad habit or some pathological problem with them — they’re just trying to show that the world is not that perfect. I think French editors at some point just started following the demands of society and consumerism. That we just need a new shampoo and a new iPhone, and we don’t want to know anything about what is happening in the world.

CC: There seems to be a growing ‘poverty and war photography fatigue’ and, as you’ve said yourself, you’re also trying to shift your lens to the reactions of people rather than the gruesome. Maybe it’s time to reinvent how we are portraying tragedies?

SP: That is a question for an editor more than a photographer, because a photographer’s job is to document. From my point of view we have to deal with what we have. I think this is why we cannot come to an exact solution, because if I were there I would probably make a different choice for what the magazine has to put on the front page. If I were there, if I could shoot this boy [Alan Kurdi] as a document of what happened, possibly I would try to do it in a different way. There were two images of that boy, one of him alone lying on the beach and one of him carried by the coastguard out of the sea. Some of them decided to use one, some the other, and it’s a very different message.

CC: You were covering the refugee crisis for five months, traveling in and out of different countries to document this overwhelming human experience from all sides. Do you agree with the term that has been used to described it, a ‘crisis’?

SP: At first I see that this crisis happened as a common epidemic. Some people — the refugees — decided that they can go to Germany and find a better life there. Facebook and the social networks exaggerated those ideas. They were constantly distributing stories about those who safely reached Germany or how they were in the process of getting there. The first time that I started working on that story, I followed a family to Serbia, then I had to leave and another photographer followed them to Sweden and, you know, they just opened me to a different world. There is an Arabic Facebook that is just overwhelmed with stories and groups about how they reached Germany or Sweden or other places, with advertisements of smugglers who offer their help to go through the Balkan countries. So everybody thought they could go, and they came to the idea that they must go. Once they started they had to reach their final destination. All the countries on the road weren’t ready for this influx of migrants and even the neighboring countries have problems and they started building fences. At the end they all decided their own country was not the destination for migrants, so they just had to provide safe passage for them — they get in, they get out, and that’s it.

The suffering of the people was just huge. They all had to deal with either riot police or the army. The police were treating them like they would treat hooligans, it was mostly migrant families or single men or those who were momentarily alone who faced riot police. That was one of the biggest human rights violations from my point of view. They were being treated very badly. Sometimes they were beating them or forcing them to stay out in the rain or the open skies for the night. They were made to march for several miles to the next registration point. And those people just lost track of where they were. Every time I met people, the first question they were asking me was which country we were in and how many countries remain until Germany.

CC: Was the general feeling among the refugees despair or hope?

SP: They were desperate to reach safety. At the beginning I was facing mostly Syrians who were trying to get to Germany, but they wanted to stay just a year or two and then go back to Syria. But at the end I found that most of the people turned out to be economic migrants from Iran, Pakistan and Morocco who just thought that social benefits and European values in Germany or in Sweden are better than home. And they were all feeling that this gate was going to be shut at some point. So they were just in a rush to get as far as they could. And that is why they were always feeling that they must go. People didn’t want to stay in a place for a day or two to rest. As soon as they reached some border they were eager to go further again.

CC: How do you see this unfolding, if people keep coming and we refuse to take them or to take adequate support measures?

SP: I just came back from Idomeni. The gate is shut right now. No more people will be able to come through this known Balkan route and Greece itself will take the main burden of migrants. Maybe some will be deported or sent back to their country. But I think that right now the European governments will have tough decisions about migrants. And this is why I really worked with those who are stuck, those who are stranded in Idomeni, in horrible conditions. They have their tents with kids or travelers and their newborn babies that are living in puddles and it’s cold,. Idomeni is the most depressing place I’ve ever seen. Because people feel that they are at a dead end. They feel trapped there and they have no place to go.

CC: Is there a particular take-away you got from the migrant story, or something that struck you in particular?

SP: It’s hard because it’s all mixed and I can’t single out one family or a story, out of hundreds that I met who had to cross the sea and then had to stay in miserable conditions. But with my Russian literature background, I was always reminded of the Nicolaj Gogol novel about the little men. It’s a very simple story but very classic about a little man who was oppressed by injustice and he opposes himself to the huge and unjust system. And this man dies in the end, trying to resist. And his enemy, or the person that in the novel oppresses him, is a government officer whose intention is to pursue justice but who was actually following their own interest. And the little man has no rights and is not able to protect himself from the injustice and he dies. At the end, thinking about that I just realized that these sufferings sometimes are making people stronger. I feel an energy from people who have their moral right to protect their civil rights. And I try to build some small stories with my images that also together tell a big story that is happening in front of our eyes.

After Rana Plaza

Innovative social media project by Ismail Ferdous documenting the horrific collapse of the Rana Plaza complex in Bangladesh and its aftermath

Interview with Ismail Ferdous by Caterina Clerici

Since starting out as a photojournalist in 2011, Bangladeshi photographer Ismail Ferdous has become known for using social media to help shed light on social issues worldwide in more immediate, powerful and innovative ways. In 2015, he was named the recipient of the 2015 Getty Images Instagram Grant winner. On February 26, 2016, one of his pictures from the massive earthquake that struck Nepal in April 2015 was among the ten showed by Instagram’s CEO and co-founder Kevin Systrom to Pope Francis when the two discussed the power of photography to bring people together.

A few months into documenting the legacy of the Rana Plaza collapse in Dhaka — the world’s deadliest industrial accident in recent years — with his “After Rana Plaza” project (supported by the Dutch Embassy), Ismail talked to SDN. He discussed the challenges and rewards of carrying out a long-term project in different formats, and the advantages of publishing on social media versus traditional platforms, in terms of audience engagement and impact.

___________________

Caterina Clerici: You’ve been working on your documentary project After Rana Plaza for eight months now (at the time of the interview, in December 2015). Tell us how the idea came about and how you got started.

Ismail Ferdous: I started the After Rana Plaza project on the second anniversary of the collapse, on April 23, 2015. I had been following the story since the Rana Plaza tragedy happened and had been documenting the garment industry. I had already done some work on the topic of the cost of fashion in a video for The New York Times, as well as a documentary and an article for a photo activism website.

More than 2,500 workers were injured in the collapse and more than 1,100 died. I thought it would be interesting to follow-up on their stories. It’s easy to forget about events like these after a while, with other news happening everywhere. But I covered the issue right after it happened, so I had a personal attachment to it. Furthermore, I see these people everyday, they are workers in the city I live in. So that’s a constant reminder for me of the importance of the project, of why their stories should be told and we should still remember what the tragedy stands for.

CC: How did you choose what format to use for the project and how did you carry it out?

IF: I asked myself what could be an interesting way to tell this story and opted for social media: everyone can access it and you don’t have to wait for traditional media to publish the content. Instagram was the preferred choice because it’s not only a fun tool, it can also be an educational one. You’re able to follow it and to hear the stories of victims directly. Then I also built a stand-alone website for readers who wanted to know more about these stories.I decided to interview one person a day, in detail, choosing not only victims but also stakeholders in the industry, like fashion designers, producers, et cetera. My aim all along has been to act as a commentator on the issue — not judging, just letting people read and think about it. It’s also meant to create a platform for those who want to be involved in the industry, to let them know more about it and make more informed choices.

CC: Why did you decide to integrate video in your work and how has the use of a ‘mixed format’ (shooting photography and video) made your project more successful on social media?

IF: I was always very fascinated by Instagram as a platform. When they started allowing you to post 15 second videos, I thought it could be a very powerful addition to the project, as I had never seen anyone using short videos like this.

Plus, as photographers we like to say that we are giving voice to the voiceless, so I thought this would be a way to actually accomplish that: you tap on the photo and you can hear the voice of the person I interviewed that day. I didn’t want to add subtitles to the videos because it would become a completely different experience, so I just chose to add a short paragraph with the subtitles instead.

CC: Did you ever feel like you were running the risk of losing focus by expanding the project on so many social media platforms (Instagram, Facebook, Twitter..)?

IF: I never felt that using social media to publish, promote and distribute my project was making me lose focus. I didn’t have to wait for someone (traditional media) to publish this project, which is already a good thing. Moreover, having different platforms makes sense at this moment because you keep your options open: someone doesn’t like Facebook and they go to Instagram, or your website, or Vimeo or Twitter. This way it’s accessible to everyone and everyone has already seen it, although I still haven’t even published it anywhere. I also want to do a book and exhibition on it, but that’s still in the works.

CC: How was your work received at home and abroad?

IF: Surprisingly, I had a bigger response internationally than locally — probably that’s because Instagram is just not that big in Bangladesh yet and, after all, the issue of garments and fashion is global.

CC: Are there any changes happening thanks to your project? Have you been able to assess its impact?

IF: Every project, every picture has an impact – sometimes it’s immediate and more visible while other times it happens more slowly or you are just creating awareness and there are no tangible effects, but I believe all projects have some sort of impact.

By doing After Rana Plaza, for instance, I found out that a lot of people didn’t even know that the place had collapsed and found out about it through the project. Many people who are working in sustainable fashion have contacted me because they want to use the work to promote social corporate responsibility, and even the International Labour Organization reached out saying they were interested in using the work to raise awareness about the cost of fashion.

Once some guys in Bolivia saw a post on Instagram about a girl who lost her mother in the collapse and asked me how to get in touch with her directly and I redirected them to the Rana Plaza compensation fund. It’s great to give people the opportunity to contribute if they feel like doing something to help out the victims and their families after they’ve read their stories. I really feel good when I get a response like that, on such a personal level. It makes me think that this is actually getting to people, that they’re touched by these stories.

CC: What is the most memorable story you’ve encountered and documented, or the one that struck you the most?

IF: It’s hard to say, because all of the stories are extremely touching. I remember once photographing a man who had lost one of his legs in the collapse and was wearing a prosthesis to walk. As soon as he started talking he burst into tears and it seemed like it was still a very heavy story for him. Only after a while he told me that he had lost his girlfriend in the collapse — and it was obviously harder for him to get over that than having lost his leg.

CC: How do you get people to share their stores with you? Is it getting more or less difficult now that you’ve kept this going for a few months, both for you and for them?

IF: To do a project like this you have to gain their trust — they have to open up — so you have to build a relationship with them. I keep in touch with many of the people I interviewed, they still call me sometimes, just to chat. Most of their stories are very sad and the whole process is very traumatizing, for them but also very draining for me too. So far though, everyone I talked to has been very welcoming to me. Society tends to forget things easily, even a catastrophe like this, so it’s always good for them to see that someone else other than them hasn’t forgotten.

_______

Ismail Ferdous is a Bangladeshi photographer based in Dhaka, Bangladesh, whose work has been featured in The New York Times, New York Times Magazine, MSNBC, National Geographic, New Yorker and TIME Lightbox, among many others.

DOCUMENTARY vs. JOURNALISM

What is the difference? Hear from two photographers & ZEKE Editor

by Paula Sokolska

Lori Waselchuk first arrived in Angola, Louisiana on a magazine assignment in 2011. A photographer with over 15 years experience including published work in Newsweek, LIFE, and The New York Times, she was there to document the Louisiana State Penitentiary’s prisoner-run hospice program.

But the “incredible journey” Waselchuk saw in the caregivers—the tenderness and care demonstrated by what society dubs hardened criminals—had her returning to Angola again and again for over two years. Her study of these “people with mostly heart and not a lot of skill making life better for others” culminated in the award-winning photo documentary series Grace Before Dying.

Even though most viewers would be stumped telling the difference between the two, a division exists in the world of visual reporting between photojournalism and documentary photography. The definitions of each are broad and the same body of work can be considered both, but as we see in the evolution of Waselchuk’s work, differences between the genres do not manifest in the finished product but in the photographer’s process and intention.

“Documentary photographers are almost always, by definition, personally driven by the subject matter and the issue,” says Glenn Ruga, ZEKE Executive Editor and a photographer whose experience chronicling issues relating to the Balkan conflicts of the 1990s, particularly Bosnia, led him to founding the Social Documentary Network.

An ignited interest means documentary photographers dedicate themselves to a subject indefinitely, with some doing so for years. Such intensive commitments are less often found in photojournalism. In the classic scenario, news breaks and a publication dispatches a full-time or freelance photojournalist to document the scene for hours or days before moving on to the next story. Today’s demanding news cycle prizes speed over depth.

Documentary work is much more challenging and much closer to the way I want my photography to work in the world. It’s more of an artist’s life. —Lori Waselchuk

“As soon as I started photographing Manenberg…I knew I was in it for the long haul,” says Sarah Stacke, a photographer who first visited the Cape Town, South Africa suburb in 2012. “I hope to be present…for milestones and daily moments well into the future.”

Manenberg was established in the 1960s when “coloured” citizens were forcefully relocated there by the apartheid government. Most people today know it as one of South Africa’s most violent neighborhoods, but Stacke’s series, Love from Manenberg, instead explores “relationships and how we navigate relationships against the backdrop of our circumstances.” She continues to visit the Lottering family, the subject of her work, to this day.

The extended time spent on documentary assignments results in emotional, intellectual, and organizational investments largely absent from photojournalism. Even though Waselchuk’s active work on Grace Before Dying is over, she admits, “I probably think about it once a day and put energy into it. The conversation the work generates is something I work on continuously.”

But according to Stacke, it also results in a deeper understanding of an individual which illuminates “the positive and negative issues that affect an individual and his or her community.” Should a photojournalist seek a similar depth of understanding, it is likely that issues of bias, reporter sympathy, and misrepresentation would arise.

“Documentary photographers have a perspective on the subject,” says Ruga. “They’re not expected to have an objective position whereas the credo of photojournalism is that you’re there to give an unbiased presentation of the material with no particular agenda.”

Photojournalism is task-driven, and in today’s demanding news cycle the medium’s purpose is to catch readers’ eyes and expound on a written narrative. For photojournalists, the professional challenge, and what publication’s pay for, is the ability to enter any situation—no matter the culture, circumstance, or resources—and come away with a captivating image.

Documentary photography is much more a labor of love, according to Ruga, who says it has never been a lucrative business. Waselchuk, who has worked several jobs to support her photography, agrees. “No one’s paying me to do this. You can’t support yourself as a documentary photographer.”

Fellowships and organizations supporting documentary work do exist, but unlike photojournalists, documentarians lack the support of editorial departments. They forego the expectation of earning money for the freedom to craft narratives and expand their skills. Not just photographers, documentarians are researchers, writers, and editors. But what marks them from photojournalists the most is their role as storytellers. Every documentary piece communicates the photographer’s personal understanding of the subject, and, in voicing the story, they become a part of it.

“Documentary work is much more challenging and much closer to the way I want my photography to work in the world,” says Waselchuk. “It’s more of an artist’s life.”

Award Winners

Honorable mentions from SDN’S call for entries on Visual Stories Exploring Global Themes/2016

ZEKE presents these four honorable mention winners from SDN’s Call for Entries on Visual Stories Exploring Global Themes. From 146 submissions, the jurors selected Jan Banning as first place winner (see Law & Order), and the four honorable mentions presented here.

ZEKE Reviews

MIRROR

by Ara Oshagan and Gor MkhitarianOshagan Editions, 2016www.araoshagan.net/mirror 166 pp.

Mirror is a new kind of photobook that draws the reader into a digitally enhanced engagement with photography and music. Photographer Ara Oshagan’s collaborator and muse in this multifaceted adventure is Gor Mkhitarian, the gifted Armenian songwriter/musician. The material in the book was created over a period of 11 years as Oshagan followed Mkhitarian from concerts to recording studios.

Aurasma is the interactive app available from iTunes and other app stores that provides the reality augmentation that makes the book more than paper. There are several pleasurable highlights when the software allows viewers to literally experience photographs jumping off the page to become dynamic music videos. In addition to the videos, most of the 20 plus pictures with accompanying Aurasma links play a related song track. Mkhitarian’s music is the ideal accompaniment for Oshagan’s mysterious pictures.

Oshagan’s visual odyssey celebrates darkness. Mkhitarian and the other musicians are often seen hovering in shadow while playing their instruments. Oshagan is a conjurer with a camera illustrating the creation of Mkhitarian’s music. Oshagan generates a cadence of pictures on the page that resonates with Mkhitarian’s lyrics interspersed throughout the book. When the Aurasma app is applied to specific pictures, their dark mood transforms to the brighter, backlit smart phone screen, and the music illuminates fresh moments of clarity.

In addition to Oshagan’s skilled use of chiaroscuro, his pictures reach out beyond the parameters of the frame acknowledging that the story is more than any one picture. The music is the muse that lets the pictures dance together. Oshagan invites his viewers to penetrate through his Mirror with the help of the highly enjoyable digital augmentations. The book is a beautifully designed package for Oshagan’s and Mkhitarian’s brilliant collaboration, and the Aurasma technology invites the viewer to walk into the Mirror and through the looking glass.

—Frank Ward

WAR IS BEAUTIFUL

The New York Times Pictorial Guide to the Glamour of Armed Conflict*By David ShieldspowerHouse Books, 2015111 pp.

In his book satirically titled War is Beautiful, David Shields levels a wholesale critique of The New York Times’ choice to accompany conflict stories with well-composed photographs. He argues that the overwhelming majority of the Times’ A1 images depicting war are too beautiful to accurately represent the atrocities of armed conflict. In the book’s subtitle, he claims that the glamourizing of war is the reason why he “no longer reads The New York Times.”

Shields points out ten “visual tropes” which organize the chapters of his book: Nature, Playground, Father, God, Pietà, Painting, Movie, Beauty, Love, and Death. To be sure, Shields’ condemnation of the the New York Times’ modus operandi is a provocative stance, and one that the paper of record itself has attempted to silence. The New York Times is currently suing Shields’ publisher, powerHouse Books, for $19,000 over the fair use of thumbnail images decorating the inside back cover of the book. But because all of these images are fully licensed, powerHouse owner Daniel Power believes that this petty legal battle is nothing short of a “First Amendment fight.”

War is Beautiful contains 64 A1 Times photographs from around the world, most of which juxtapose American soldiers clad in desert camouflage against the recognizably Middle Eastern backdrops of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Palestine. In an interview with Rita Banerjee of Electric Literature, Shields laments how “remarkably hollow and bloodless, composed, and abstract” the photographs in the book appear. And it would be difficult to argue that the images themselves are devoid of the beauty he accuses them of possessing — from the glowing sunset over the Euphrates River to the sparkling green eyes of orphaned Iraqi children, the Times has been intentional in representing the artistic as well as the journalistic. However, it would also be a misrepresentation to claim that all of the images are bloodless – in Pietà alone, four of the five images Shields uses are of the dead and maimed, and three of these show mortal wounds and bloodied clothing. Nevertheless, Shields sees the aesthetic qualities of these photographs as an injustice to and a sanitizing of the horrors of war, arguing that they convey the sense that war is “heck” rather than “hell.”

So the question remains: do war images have to be uncomfortable to be successful, graphic to be moral? Pick up a copy of War is Beautiful (or a copy of The New York Times) to decide for yourself.

—Emma Brown

FACE OF COURAGE

Intimate Portraits of Women on the Edgeby Mark TuschmanVal de Grace Books, 2015344 pp.

Mark Tuschman uses captivating portraits to tell the stories of women from all over the world in his new book Faces of Courage: Intimate Portraits of Women on the Edge. He weaves the women’s individual experiences into a beautiful tapestry of personal narratives that, taken together, evidence the systemic nature of the trials and tribulations faced by women worldwide. Many of the women and girls featured are survivors of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, and are limited by the barriers to opportunity characteristic of male-dominated cultures. Tuschman prefaces each chapter with moving accounts of his encounters with these women, which he then follows with his arresting images. In these portraits, some women are stoic, some offer a smile, and some seem on the verge of tears. Regardless of expression, their eyes burn with resolve. Their gazes, like their spirits, seem unbreakable.

To be sure, violence against women is a “regular, daily occurrence” according to Tuschman. The book shows the myriad ways in which women are reconstructing ideas about their own self-worth such as learning that they are entitled to basic human rights including the right to decide how many children they have, the right not to be beaten or treated like chattel, and that they are more than simply “unpaid domestic labor, sexual objects, and reproductive vessels.”

Fortunately, many organizations and activists like the ones Tuschman features in his book are working to combat this reality. In the final chapters, he highlights what he calls “tools of empowerment”: vocational training, microfinance, and education. These programs support the well-being and endeavors of marginalized women, raising them up and helping them reach their potential socially, politically, and economically.

—Emma Brown

IT’S WHAT I DO

A Photographer’s Life of Love and WarBy Lynsey AddarioNew York, NY: Penguin Press, 2015368 pp.

In It’s What I Do, conflict photographer Lynsey Addario turns the lens on her own experiences in order to reveal the complexities and contradictions of her life as a journalist. This identity has saved Addario’s life and put her in mortal danger, gained her exclusive access and limited her mobility, left her mocked and ridiculed and earned her the title of genius by the MacArthur Foundation. But for Addario, photojournalism is much more than a profession; it is her calling. This passion for photography and humanitarianism has helped her maintain a sense of self in an endlessly paradoxical world where she bears witness to the full spectrum of poverty and privilege, occupation and freedom, death and birth.

In the world of journalism, Addario is known for her artistic talent but also her sincerity — it is her ability to photograph aesthetically beautiful images without sacrificing candor that has earned her countless accolades and global renown. Her book is certainly no exception. Addario succeeds in telling her own narrative with the same authenticity that characterizes her photojournalism. She honors her successes as well as her failures, her pride and her pain, her confidence and her insecurities. It is her ability to embrace life’s complexities without sugarcoating that makes her photography and her writing impossible to put down, to turn away from, to forget.

Like her masterful photography, Addario’s book It’s What I Do triumphs in navigating the many balancing acts of journalism: it is illuminating without being exploitative, and it honors her faithfulness to honest, empathetic reporting without being self-indulgent. The book itself represents the best of Addario’s talents as both an artist and a storyteller. On page after page, her words, complimented by interspersed photographs, create crisp and vibrant imagery in the reader’s mind. Addario recounts scenes from her life with careful attention to each intricate detail, bringing to her writing the same intriguing dynamism that characterizes her award-winning photography. It’s What I Do is poignant and compelling — Addario successfully mobilizes her personal experiences and nuanced approach in order to shed light on some greater truths about conflict photojournalism, humanitarianism, and the human condition.

—Emma Brown

Featured Photographer of the Month

August 2015-January 2016

Each month SDN presents the Featured Photographer of the Month Award to one photographer whose work we feel best exemplifies visual storytelling and documentary photography at its best. We highlight this work in our monthly email Spotlight.

Masthead

ZEKE is published by Social Documentary Network (SDN), an organization promoting visual storytelling about global themes. Started as a website in 2008, today SDN works with more than 1,500 photographers from around around the world to tell important stories through the visual medium of photography and multimedia. Since 2008, SDN has featured more than 2,000 exhibits on its website and has had gallery exhibitions in major cities around the world. All the work featured in ZEKE first appeared on the SDN website, www.socialdocumentary.net.

Spring 2016 Vol. 2/No. 1

ZEKE Staff

Executive Editor: Glenn RugaEditor: Barbara AyotteCopy Editor: John RakIntern: Emma Brown

Social Documentary Network Advisory Committee

Barbara Ayotte, Medford, MASenior Director of Strategic CommunicationsManagement Sciences for Health

Kristen Bernard, Salem, MAMarketing Web DirectorEBSCO Information Services

Lori Grinker, New York, NYIndependent Photographer and Educator

Steve Horn, Lopez Island, WAIndependent Photographer

Ed Kashi, Montclair, NJMember of VII photo agencyPhotographer, Filmmaker, Educator

Reza, Paris, FrancePhotographer and Humanist

Jeffrey D. Smith, New York NYDirectorContact Press Images

Steve Walker, New York, NYConsultant and educator

Frank Ward, Williamsburg, MAPhotographer and Educator

Jamie Wellford, Brooklyn, NYPhoto Editor, Curator

ZEKE is published twice a year by Social Documentary NetworkCopyright © 2016Social Documentary NetworkPrint ISSN 2381-1390Digital ISSN: Forthcoming

ZEKE does not accept unsolicited submissions. To be considered for publication in ZEKE, submit your work to the SDN website either as a standard exhibit or a submission to a Call for Entries. Contributing photographers can choose to pay a fee for their work to be exhibted on SDN for a year or they can choose a free trial. Free trials have the same opportunity to be published in ZEKE as paid exhibits.

To subscribe:www.zekemagazine.com

Advertising inquiries:glenn@socialdocumentary.net

Social Documentary Network61 Potter StreetConcord, MA 01742 USA617-417-5981info@socialdocumentary.netwww.socialdocumentary.netwww.zekemagazine.com@socdoctweets

Cover photo by Daro Sulakauri. Georgia. Leila fell in love with a boy that she met online. She escaped from her home and crossed the border from an occupied territory of Georgia to marry.

Contributors

Photographers and writers featured in this issue of ZEKE Magazine.

Jan Banning

Photographer Jan Banning was born in Almelo in 1954 and currently lives in Utrecht, Netherlands. He studied history at the Radbout University of Nijmegen before becoming a photographic artist. He puts the social and political environment at the fore of his work and often features subjects that have been neglected within the arts and are difficult to portray: state power, consequences of war, justice, and injustice. His project “Bureaucratics,” a comparative study of government officials, showcases his academic, socially conscious approach. This exhibition earned Jan worldwide recognition, and it was shown in museums and galleries in some 20 countries on five continents.

Among Banning’s books are Traces of War (2005), Comfort Women (2010), and Down and Out in the South (2013). Among Banning’s many awards is a World Press Photo Award. His documentary artwork has been widely published and is featured in both private and public collections, including the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Lisa Liberty Becker

Lisa Liberty Becker has written 90-plus articles for publication in Boston magazine, Boston Sunday Globe, Boston Globe magazine, Sports Illustrated Women, Women’s Basketball magazine, and others. She also has one published nonfiction book.

In addition to being a writer, Lisa is also an editor and a writing instructor. She lives in the Boston area and is currently working on her second book.

Caterina Clerici

Caterina Clerici is an independent multimedia journalist based in New York. A graduate of Columbia Journalism School, she’s currently a freelance photo editor at TIME and the Special Issue Editor at SDN. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, La Stampa, Libération, Die Zeit, among others. You can follow her at @caterinaclerici.

Ara Oshagan

Ara Oshagan’s work revolves around the themes of identity, community and bearing witness. Since 1995, he has been photographing and recording the oral histories of survivors of the Armenian Genocide of 1915 — a collaborative work with Levon Parian and the Genocide Project, iwitness. For over eight years, Ara photographed extensively in Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia for Father Land, a book project with his father, author Vahe Oshagan. Father Land was exhibited at the LA Municipal Art Gallery at Barnsdall Park from December 2010 to Februrary 2011 and at the powerHouse Arena Gallery in NY in December 2010.

Ara received a California Council on the Humanities Major Grant in 2001 to photograph the Armenian experience of Los Angeles. This work, “Traces of Identity,” was exhibited at the LA Municipal Art Gallery at Barnsdall Park and at the Downey Museum of Art.

Ara has received a grant from the California Council on the Humanities to photograph Ethiopian life in Los Angeles. In 2012, Ara spoke at the TEDxYerevan event, presenting a talk on “The Documentary Image as Identity.” That same year, he did a photographic/ architectural installation on the theme of “(Re)Population.” Ara’s work is currently in the permanent collection of the SouthEast Museum of Photography in Florida, the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena, Downey Musuem of Art in Downey, California, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Yerevan, Armenia. Recently he has published A Poor Imitation of Death, a collaborative portrait of youth in the California prison system, and Mirror, reviewed in this issue of ZEKE.

Jordi Pizarro

Jordi Pizarro Torrell was born in Barcelona, Spain in 1985. He is a freelance documentary photographer currently based in New Dehli, India. He is mostly interested in his personal reportages, but also covers breaking news in South Asia. He currently is working on a long-term project entitled “Believers” which looks at traditions, cultures, and religions from an anthropological perspective in many different regions globally. He was awarded an honorable mention for this work from SDN in 2015.

The emphasis of Jordi’s work is largely focused on current social and environmental concerns that affect different communities, most of them not covered by major media. His main goal is to aid and increase awareness of issues affecting people and their environments in the world we live in, and he hopes that his photographs will contribute in some small way towards creating a more critical reflection of this world. He has been published in many international magazines including The New York Times, National Geographic, Time, Sunday Times, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, Forbes, and El País. His work has been shortlisted for many awards and scholarships, earning recognition from Pictures Of the Year International (POYI), PDN Storytellers, Sony World Photography Awards, Burn Magazine, San Jose Foto, LensCulture Exposure Award, and Lucie Foundation, among others.

Margaret Quackenbush

Margaret Quackenbush is a freelance reporter based in Boston. She graduated with a master’s degree in journalism from Boston University in January 2016. Her writing has appeared in the Boston Business Journal, The Dorchester Reporter, Eater Boston and other publications in the Boston area.

She was the 2016 coordinator for Boston University’s annual Power of Narrative conference, and was previously the managing editor of the Boston University News Service and a teaching assistant at BU. Margaret received a BA in English and history from St. Lawrence University in 2010 and previously worked at WGBH, Boston’s PBS station.

Probal Rashid

Probal Rashid is a documentary photographer and photojournalist working in Bangladesh, represented by Zuma Press, USA. He earned a post-graduate diploma in photojournalism at the Konrad Adenauer Asian Center for Journalism (ACFJ) at Ateneo De Manila University in the Philippines through a World Press Photo scholarship program. He also holds an MBA.

His work has been published in many national and international newspapers and magazines such as National Geographic, Forbes, GEO, New York Post, Days Japan, Paris Match, The Wall Street Journal, Stern, RVA, The Telegraph, Focus Magazine and The Guardian. Moreover, his photographs have been exhibited in Bangladesh, Germany, Indonesia, Japan, Thailand, Malaysia, UK, and USA. Additionally, the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts selected some of his works for their permanent collection.

Probal is the recipient of numerous awards for his work including the Pictures Of the Year International (POYi), Days Japan Photojournalism Award, China International Press Photo Award (CHIPP), NPPA’s Best of Photojournalism Awards, Yonhap International Press Photo Awards, KL International Photo Award, FCCT/OnAsia Photojournalism, “Zoom-in on Poverty” Global Photo Award, CGAP Microfinance Photo Award, WPGA Annual Pollux Awards in UK, International Year of Biodiversity Award, and the Atlanta Photojournalism Seminar Contest.

Anne Sahler

Anne Sahler is an internationally published writer, photographer and graphic designer who divides her time between Japan and her homeland of Germany. She holds a master’s degree in Cultural Studies, History of Art and Religious Studies which fuels her interests in Japan, art and social activism. Her curious nature and never ending need for travel helps lend a clarity of prospective to an evermore complicated world.

Paula Sokolska

Paula Sokolska is a freelance journalist in the Boston area and the Strategic Communications Associate at Health Leads. She has a B.S. in Journalism from Boston University where she specialized in science and narrative writing.

She has written for BU Today, BU News Service, Zeke: The Magazine of Global Awareness, and Spotted by Locals

Jamey Stillings

Jamey Stillings, originally from Oregon, earned a BA in Art from Willamette University (1978), and an MFA in Photography from Rochester Institute of Technology (1982). Over three decades, Stillings built a commercial photography business, integrating both fine art and documentary work. In 2009, Stillings embarked on a personal project, “The Bridge at Hoover Dam,” documenting its monumental construction over the Black Canyon of the Colorado River. Work from the bridge project has been published in over twenty magazines around the world and has won many awards. It has also been exhibited in numerous solo and group exhibitions, including the 2013 London exhibition “Landmark –- The Fields of Photography,” curated by William Ewing.

Stillings continues to seek new opportunities to integrate his aesthetic interest in the human-altered landscape with concerns for environmental sustainability. In October 2010, he commenced aerial photography over the future site of the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System in the Mojave Desert of California. “The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar” has received The Epson Creativity Award in the PDN Photo Annual 2015, First Place Fine Art in the APA Awards 2014, and First Place in the 2013 International Photography Awards (IPA) in the Editorial Environmental Professional category, among others. First published in June 2012 by The New York Times Magazine, this work has since been published around the world. Photographs from the project have been exhibited in the United States, the Netherlands, and Colombia. “The Evolution of Ivanpah Solar” is now both an exhibition and a book (Steidl, 2015). Stillings’ extended project, “Changing Perspectives,” will build upon the Ivanpah Solar body of work by expanding his look at contemporary energy development. Over the next few years, Jamey’s goal is to develop “Changing Perspectives” into a global study.

Daro Sulakauri

Daro Sulakauri was born in Tbilisi, Georgia in 1985. After obtaining a degree from the Department of Cinematography at the Tbilisi State University, Daro moved to New York to study photojournalism at the School of the International Center of Photography (ICP). Before graduating in 2006, she was awarded the John and Mary Phillips Scholarship and recognized by the ICP Director’s Fund. Upon finishing, she returned to her native Georgia and continued doing photojournalism. She earned second place in the Magnum Foundation’s Young Photographer in the Caucasus contest for her series “Terror Incognita.” She was recognized by PDN as one of their “30 Under 30 / Women Photographers.” She also has won many other awards, including the 7th Julia Margaret Cameron Award, LensCulture Visual Storytelling awards, the EU Prize for Journalism, Human Rights House in London, shortlisted for the Magnum Foundation’s Emergency Photographers Fund, OSF grant, and more.

Daro is now based in Georgia, where she documents social issues of the Caucasus. Her work has been published in many well-known publications such as Forbes, Mother Jones, Sunday Times, New York Times Lens, Saveur, The Economist, Vision, and Bloomberg.

Jan Zychlinski