This is Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon’s second report to the General Assembly regarding Special Political Missions, including good offices, and preventive diplomacy and post-conflict peacebuilding missions. It comes at a time when our Organization, and the international system as a whole, face strains and pressures that test their resilience and strength as never before. By their sheer number, but also by their gravity, the challenges to international peace and security are today, I believe, the gravest we have seen since at least the end of the Cold War.

Armed conflict, natural disasters, environmental degradation and other crises have conspired to produce more refugees, displaced people and asylum seekers than at any other time since the creation of the United Nations.

As the Secretary-General told the General Assembly during the General Debate a few weeks ago, never before has the United Nations been asked to reach so many people with emergency food assistance and other life-saving supplies.

In the past few months, we have been shocked by horrific scenes in various regions across the globe. In Iraq and Syria, thousands have fallen victim to nihilists who not only murder, rape and enslave, but gloat about their crimes and flaunt their ambition to wreak havoc on the broader region.

In West Africa, a virus threatens to reverse tenuous gains in peace, security and development, as borne out by the heartrending scenes of people left waiting to die for lack of medical facilities and care.

In Europe, while a series of protracted conflicts continue to cause hardship for those involved, fresh conflict has broken out again, causing suffering and displacement on a large scale.

Thus, to quote the Secretary-General again, diplomacy is on the defensive, undermined by those who believe in violence or who would throw up their hands in despair. It is precisely at times like these that the work of our Organization is the most important.

Active around the world

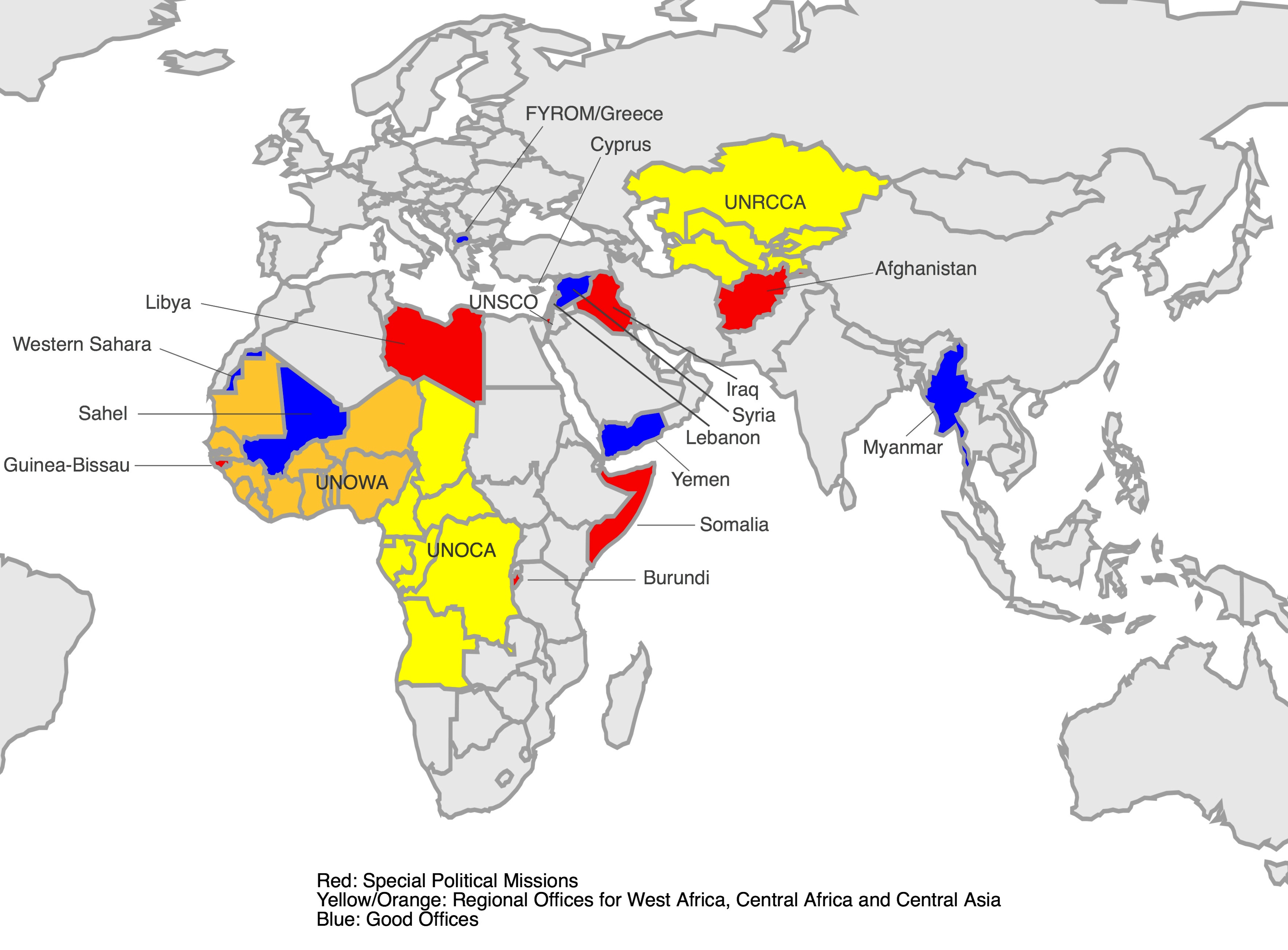

Special Political Missions, managed by the UN Department of Political Affairs, are active in many of the areas wracked by or recovering from conflict in Africa, Central Asia and the Middle East. These Missions, or SPMs, are a central tool for international action and attention to assist host countries overcome conflict and support national efforts to build a sustainable peace.

The report provides an overview of 35 Special Political Missions authorized by the Security Council or the General Assembly to help countries emerging from conflict or to address other important issues in relation to the maintenance of international peace and security.

Roles of the Security Council and the General Assembly

The UN Charter gives the Security Council the primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security. In fulfilling that responsibility, the 15-member Council can establish a UN Special Political Mission, extend its mandate, or choose to end its work.

Out of the 35 current missions discussed here, 33 are mandated by the Security Council and two by the General Assembly. One of the latter ones is the Office of the Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on Myanmar, Vijay Nambiar, whose mandate is open-ended and under consideration by the 193-Member General Assembly.

Newest Special Political Missions

Two new Special Political Missions were added in the past year, the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic and the Panel of Experts for Yemen.

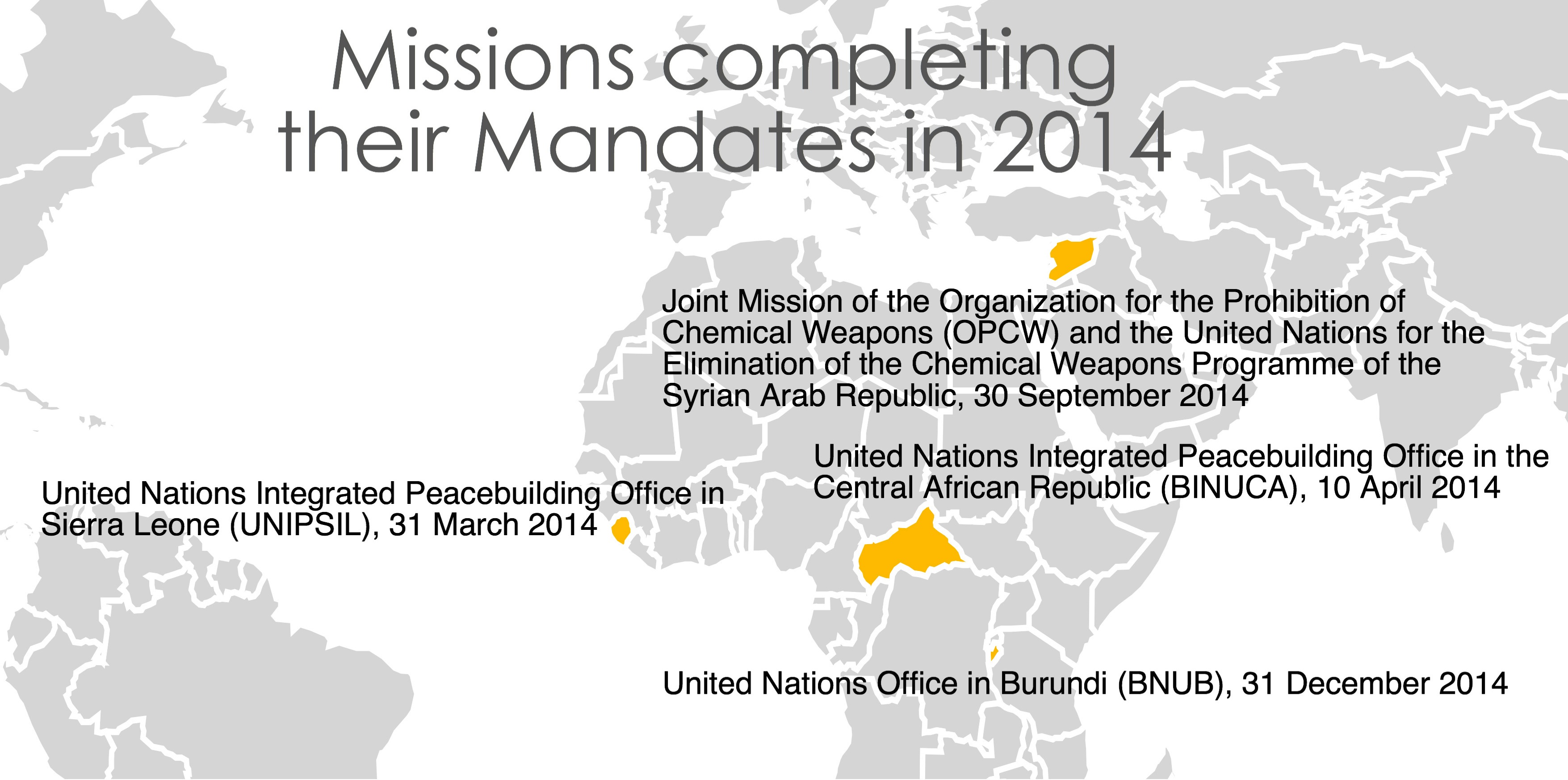

Missions completed in 2014

The mandates of four Missions end during the course of 2014: the United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in the Central African Republic (BINUCA); the United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Sierra Leone (UNIPSIL); the United Nations Office in Burundi (BNUB); and the Joint Mission of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons and the United Nations for the Elimination of the Chemical Weapons Programme of the Syrian Arab Republic.

Ongoing Special Political Missions

Twelve Missions have open-ended mandates:

(1) the Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on Cyprus , currently held by Espen Barth Eide

(2) the Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on the Prevention of Genocide, Adama Dieng

(3) the Personal Envoy of the Secretary-General for Western Sahara, Christopher Ross

(4) the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for the implementation of Security Council resolution 1559 (2004) on Lebanese sovereignty, Terje Roed-Larson

(5) the United Nations Representative to the Geneva International Discussions, Antti Turunen

(6) the Office of the Special Envoy for the Sudan and South Sudan, Haile Menkerios

(7) the Office of the Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on Yemen, Jamal Benomar

(8) the United Nations Regional Centre for Preventive Diplomacy for Central Asia (UNRCCA), Miroslav Jenca

(9) the Office of the United Nations Special Coordinator for Lebanon (UNSCOL), Derek Plumbly

(10) the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for the Sahel, Hiroute Guebre Sellassie

(11) the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for the Great Lakes Region, Said Djinnit

(12) and the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria, Staffan de Mistura

The Office of the UN Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process (UNSCO), headed by Robert Serry, and the UN Office to the African Union (UNOAU), headed by Special Representative of the Secretary-General Menkerios, are also included in this category.

The remaining 22 Special Political Missions have madates that will be up for renewal in the remaining months of 2014 or later. They include Panels of Experts – who are appointed by the Secretary-General to aid Security Council Committees established to monitor, promote and facilitate the implementation of measures of a resolution, often related to sanctions – as well as United Nations offices and large political (as opposed to peacekeeping) missions in the field.

(1) the Group of Experts on Côte d’Ivoire

(2) the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo

(3) the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea

(4) the Panel of Experts on the Sudan

(5) the Panel of Experts on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

(6) the Panel of Experts on the Islamic Republic of Iran

(7) the Panel of Experts on Liberia

(8) the Panel of Experts on Libya

(10) the Panel of Experts on Yemen

(11) the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic

(13) the Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate

(14) the United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Guinea-Bissau (UNIOGBIS)

(15) the United Nations Regional Office for Central Africa (UNOCA)

(16) the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL)

(17) the United Nations support for the Cameroon-Nigeria Mixed Commission (CNMC)

(18) the United Nations Office for West Africa (UNOWA)

(19) the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM)

(20) the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI)

(21) the United Nations Electoral Observation Mission in Burundi (MENUB)

(21) the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA)

In the video above, the outgoing head of UNAMA, Special Representative of the Secretary-General Jan Kubis, discusses the 2014 presidential election run-off in Afghanistan and the UN’s role in supporting the Afghan-led electoral process.

Secretary-General’s good offices

UN PHOTO: THE SECRETARY-GENERAL’s SPECIAL ADVISER ON CYPRUS, ESPEN BARTH EIDE (CENTRE), MEETING IN SEPTEMBER 2014 WITH NICOS ANASTASIADIS (LEFT), GREEK CYPRIOT LEADER, AND DERVIŞ EROĞLU, TURKISH CYPRIOT LEADER.

“Special Political Missions (SPMs) have become an indispensable instrument for the maintenance of international peace and security. They are also the most visible manifestations of the Secretary-General’s good offices.”

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in his first thematic report on Special Political Missions to the 193-member General Assembly, 2013

Historical evolution of Special Political Missions

Photo: Secretary-General U Thant (right) is seen conferring with Jose Rolz-Bennett, Deputy Chef de Cabinet. At left is Ole Algard of Norway, and in back of the Secretary-General is Ralph J. Bunche, Under-Secretary for Special Political Affairs, 1963. UN Photo

Political missions have been at the very centre of United Nations efforts to maintain international peace and security since the establishment of the Organization. From the deployment of Count Folke Bernadotte to the Middle East in 1948 to the establishment of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia in 2013, political missions have, in different forms, played a vital role in conflict prevention, peacemaking and peacebuilding.

Although the term “Special Political Missions” emerged only in the 1990s, the history of United Nations civilian missions with political functions goes back much further.

The historical evolution of Special Political Missions has three distinctive eras: the first period of new missions design (1948-early 1960s); a second period of relative inactivity (late 1960s – late 1980s); and a third period of rediscovery (post-Cold War). This evolution was part of a broader trend of increased reliance by the United Nations on different mechanisms to promote and sustain peace and security.

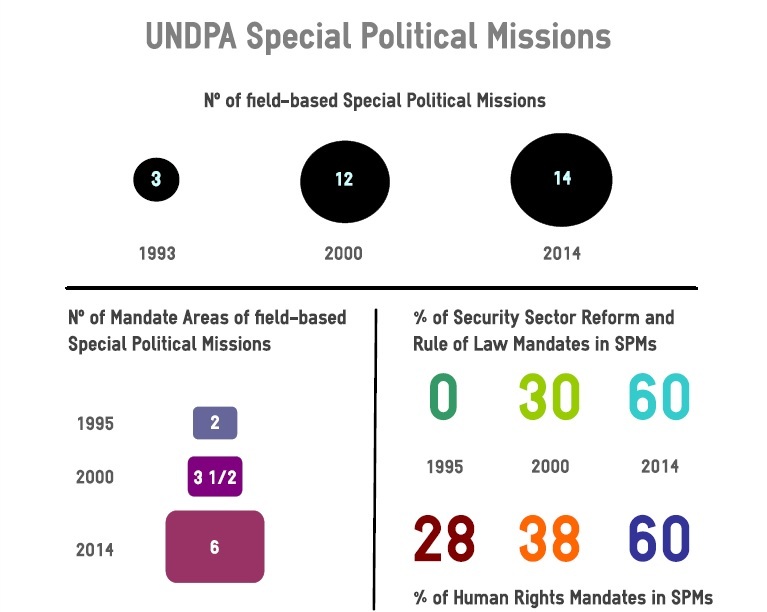

Trends: More complex mandates

PHOTO: UNAMI REPRESENTATIVES MET IN MARCH 2014 WITH IRAQIS OF DIFFERENT FAITHS AND RELIGIONS IN THE CITY OF NAJAF. UNAMI

The number of Special Political Missions has grown over the past two decades. In 1993, there were only three SMPs in the field. This number increased to 12 in 2000 and reached 14 in 2014. The increase in the overall number of Special Political Missions is only part of the story. Individually, the mandates of these Missions have become significantly more complex than at the outset, when they were tasked primarily with reporting and monitoring tasks. Especially over the last decade, field-based Special Political Missions have become manifestly multidimensional operations, in line with an expanding normative agenda, combining political tasks with a broader set of mandate areas such as human rights, rule of law and security institutions, and sexual violence in conflict and child recruitment.

Women’s role in peacebuilding

PHOTO: IN MALHA, NORTH DARFUR, WOMEN ATTEND AN OPEN DAY WORKSHOP TO DISCUSS THE PRINCIPLES AND PROGRESS RELATED TO UN SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTION 1325. UNAMID/SOJOUD ELGARRA

One area in which the normative agenda of Special Political Missions has increased significantly is the role of women in peace and security, particularly since the adoption of Security Council resolution 1325 in 2000. Special Political Missions have been particularly involved in efforts to promote women’s participation in conflict resolution and peace processes, and to incorporate a gender perspective in their overall peacebuilding work.

Mediation

Given their relatively lean structure and light footprint, Special Political Missions often have to rely on support from Headquarters in specific thematic areas, from rule of law and constitution-making to electoral assistance. One of the key areas in which special political missions have required particular support over the past few years, in addition to good offices, is mediation.

Over the past few years, the United Nations has enhanced its operational readiness to implement and support mediation efforts. The Mediation Support Unit, in the Department of Political Affairs complements expertise available elsewhere in the United Nations system and serves as the central hub for mediation support, capable of assisting the peace efforts of the United Nations, Member States, regional organizations and others. Among its functions, MSU provides advisory, financial and logistical support to peace processes; works to strengthen the mediation capacity of regional and sub-regional organizations; and serves as a repository of mediation knowledge, policy and guidance, lessons learned and best practices.

An important asset in the Organization’s rapid response capability is the Standby Team of Mediation Experts. These experts, deployable within 72 hours, are specialists in mediation process design, constitution-making, gender and inclusion issues, sharing of natural resources, power-sharing and security arrangements. Download the 2014 Standby Team’s fact sheet.

Top row, from left: Christina Murray (Constitutions); Jeffrey Mapendere (Security Arrangements); Marie-Joëlle Zahar (Power Sharing); Hassen Ebrahim (Constitution-making, Process Design)

Bottom row: Sven Koopmans (Process Design); Rina Amiri (Process Design, Gender and Social Inclusion); Michael Brown (Natural Resources); Pierre-Yves Monette (Process Design)

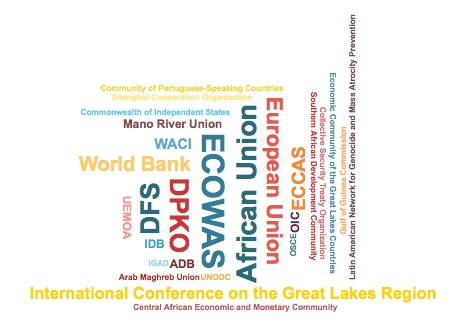

Partnerships

Partnerships have taken a wide range of modalities and covered various areas, reflecting the growing diversity and complexity of cooperation between the United Nations and regional actors. Regionally-mandated envoys, for example, have, by the nature of their mandate, a close relationship with regional actors in the areas in which they operate. In particular, given their focus on addressing cross-boundary issues and challenges, their cooperation with regional actors is critical in many cases.

In some instances, cooperation with regional actors is a crucial part of their mandates. The United Nations Office in West Africa (UNOWA) is mandated to enhance sub-regional capacities for conflict prevention, conflict management, mediation, and good offices, including providing support to existing sub-regional mechanisms, in particular, the Conflict Prevention Framework of the ECOWAS and the Community’s Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management, Resolution, Peacekeeping and Security.

Similarly, the United Nations Office in Central Africa (UNOCA) is mandated to cooperate with ECCAS, the Central African Economic and Monetary Community, the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region, the Economic Community of the Great Lakes Countries and other key partners in the region, providing assistance to their efforts to promote peace and stability in the broader Central African sub-region. Both UNOWA and UNOCA have worked with regional partners such as ECOWAS, ECCAS and the Gulf of Guinea Commission to prepare a regional anti-piracy strategy for the Gulf of Guinea.

Security in the field

“We have long known that the blue flag sadly does not afford us the protection it once did. But the growing scope — geographic and normative — of our operations also increases our exposure.”

Under-Secretary-General Feltman in his speech to the General Assembly, 2014

In 2014, there was a deterioration of the security situation in several countries in which special political missions operate, which created greater risks for United Nations personnel and assets, and posed significant obstacles for mandate implementation across various areas. Special Political Missions have been called upon to deliver complex mandates in situations of active conflicts, or barely postconflict contexts. Volatile security environments hinder the Organization’s ability to interact with national stakeholders – both government and civil society – in particular in more remote areas away from urban centers. Other areas of mandate implementation – such as humanitarian assistance, disarmament and demobilization or electoral assistance – may also be affected.

In order to cope with these less permissible environments for United Nations operational work, the Organization has developed a menu of security options to minimize security risks while providing missions with the ability to implement their mandates. One of the options that has been explored in recent years is the deployment of Guard Units. A Guard Unit is a force composed of police or military personnel, or other State security forces, provided as contingents by one or more Member States and deployed with the authorisation of the Security Council or the General Assembly to protect United Nations personnel, premises and assets in field missions operating in non-permissive environments.

A lessons-learned exercise will be undertaken by the Departments of Safety and Security, Political Affairs and Peacekeeping Operations with the Office of Coordination for Humanitarian Affairs and relevant operational agencies by mid-2015 to review the use of Guard Units.

Downloading the full report

The full report is available for downloading as a or can be shared through this link http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/69/363. The report is marked as A/69/363.