LONGFORM REPRINTS

This article originally appeared in The New York Times Magazine and is reprinted on Longform by permission of the author.

IT WAS A BEAUTIFUL Thursday morning in May, and everything was going wrong. James Turrell had six days to prepare for the biggest museum exhibition of his life — 11 complex installation pieces at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art — but he didn’t have a single work finished, and he was missing crucial parts.

He shuffled into the office of LACMA’s director, Michael Govan, and flopped into a chair with a sigh.

“I’m pretty concerned,” Turrell said. “You know, the computer that came back from Russia was completely wiped.”

Govan tapped a foot underneath the table. The computer was essential. Much of Turrell’s work consists of special rooms that are infused with unusual light, and the computer helps run the show. It had been in Russia for another exhibition, but something went awry in transit.

“There’s nothing in it,” Turrell said. “Nothing’s in it at all! Nothing.”

Govan shook his head calmly. “That happens in Moscow,” he said.

Turrell shifted uncomfortably in his seat. “I guess,” he said. “I don’t have a piece that’s finished yet. You know, it’s getting late on everything.”

“Has the lens left Frankfurt?” Govan asked. This was another essential part.

“No, it hasn’t left Frankfurt,” Turrell said.

“I thought it did,” Govan said.

“No, no,” Turrell said. “It has not left Frankfurt. I don’t know what’s going on.”

Now it was Govan’s turn to sigh. “You should have been a painter,” he said. “Five years of planning, three months of construction, and there’s not one work of art.”

The plan had been simple on paper: Turrell would open three major shows inside a month. As soon as he finished the LACMA pieces, he would race to Texas for another huge installation at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and then to Manhattan, where he is opening a show at the Guggenheim next week. Taken together, the three-museum retrospective is the biggest event in the art world this summer. As the curator of the Houston exhibition, Alison de Lima Greene, put it, “This is the first time that three museums have mounted exhibitions of this magnitude in conjunction, all devoted to a single artist.” In total, the retrospective takes up 92,000 square feet.

Assembling any Turrell show is a complicated affair. Unlike a show of paintings and sculpture, every piece must be built on site, and even more than with most installation art, his work requires elaborate modifications to the museum itself. Windows must be blocked off or painted black to obscure the outside light; zigzagging hallways are constructed to isolate rooms; and each of the rooms has to be built according to Turrell’s meticulous designs, with hidden pockets to conceal light bulbs and strange protruding corners that confuse the eye. Even the drywall must be hung and finished with exacting precision, so that each corner, curve and planar surface is precise to 1/64th of an inch. It can take hundreds of man-hours to finish a single room; he was erecting 11 at LACMA.

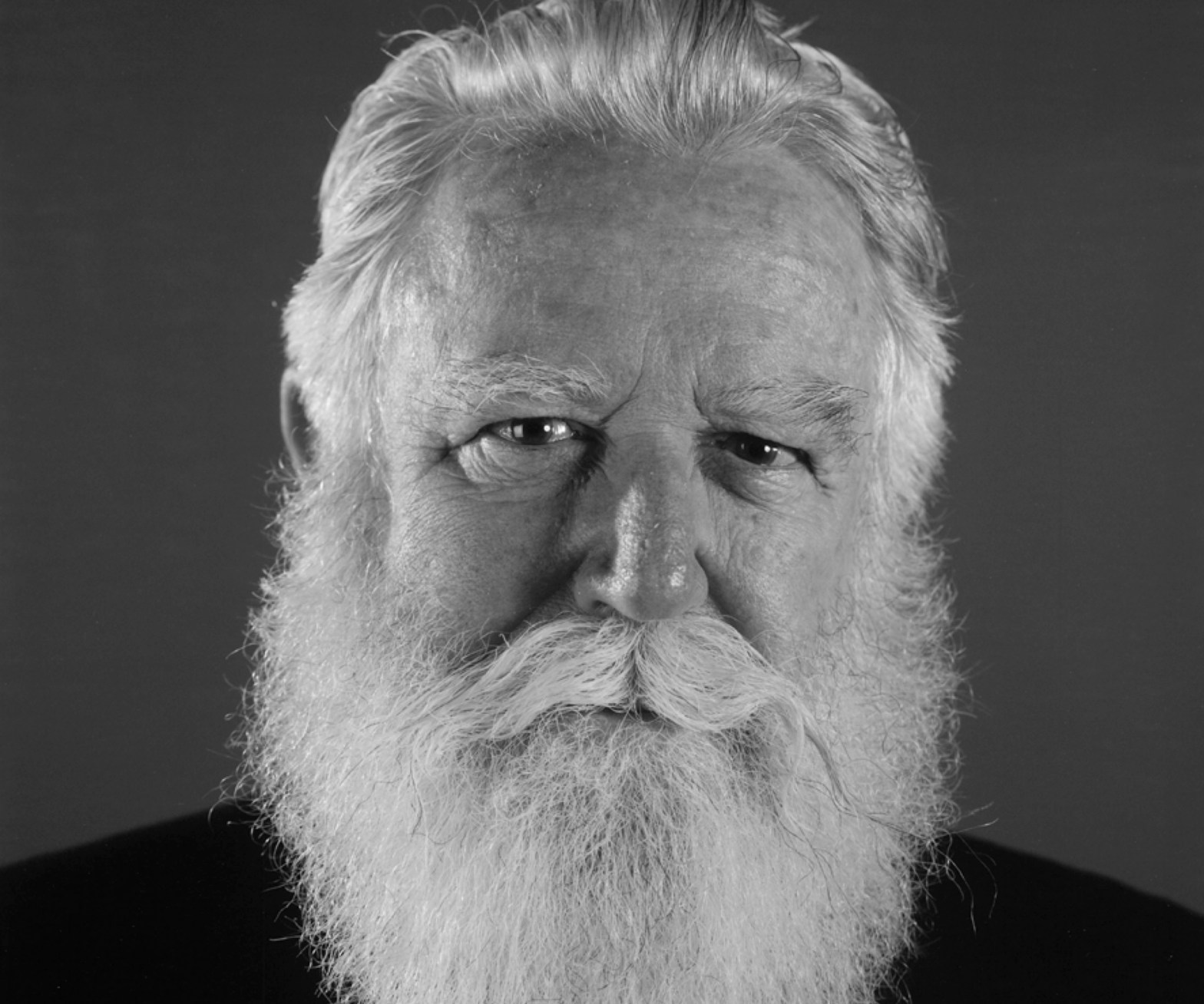

Turrell at 70 is a burly man with thick white hair and a snowy beard. He tends to dress in dark clothing, like Santa Claus in mourning. We had been spending a lot of time together as he prepared for the shows, and I had followed him to Los Angeles to see the final stages. After the conversation with Govan, I retreated outside and found a bench in the shade to do some reading. I expected to be there a while. Two hours later, I looked up and saw Turrell standing there with a smile. “Well,” he said, “we’ve got one ready. Come on, let’s take a look.”

I followed him inside the building, and we rode an elevator to the second floor. We stepped into a dim lobby filled with construction equipment. “This way,” he said, turning into a dark hallway. I walked behind, my hands groping for the walls. Turrell stayed a few steps ahead, muttering directions — “forward now, another step, this way, and turn” — until I rounded the final corner and saw the piece materialize before me. It was a looming plane of green light that shimmered like an apparition. The rush of blood to my head nearly brought me to my knees.

***

IT IS DIFFICULT TO SAY much more about the piece without descending into gibberish. This is one of the first things you notice when you spend time around Turrell. Though he is uncommonly eloquent on a host of subjects, from Riemannian geometry to vortex dynamics, he has developed a dense and impenetrable vocabulary to describe his work. Nearly everyone who speaks and writes about Turrell uses the same infernal jargon. It can be grating to endure a cocktail party filled with people talking about the “thingness of light” and the “alpha state” of mind — at least until you’ve seen enough Turrell to realize that, without those terms, it would be nearly impossible to discuss his work. It is simply too far removed from the language of reality, or for that matter, from reality itself.

The piece that day at LACMA, for example, was one of his “Wedgeworks” series. The room was devoid of boundaries, just an eternity of inky blackness, with the outline of a huge lavender rectangle floating in the distance, and beyond it, the tall plane of green light stretching toward an invisible horizon, where it dissolved into a crimson stripe.

I suppose it would be fair to say that all of this was an illusion. The shapes and contours I saw were made entirely of light, while the actual walls of the room were laid out in a way I could never have guessed. When, after a few minutes, a museum worker accidentally flipped on a bright light, I was surprised to see a small chamber in the back, with a workman’s ladder propped against the wall. Turrell lurched toward the doorway in a panic, crying out, “What the hell are they doing?”

Other pieces by Turrell are even more disorienting. His “Dark Spaces” can require 30 minutes of immersion before you begin to see a swirling blur of color, while some of his rooms are so flooded with light that the effect is instantly overpowering. Stepping into one of his “Ganzfeld” rooms is like falling into a neon cloud. The air is thick with luminous color that seems to quiver all around you, and it can be difficult to discern which way is up, or out.

Not everyone enjoys the Turrell experience. It requires a degree of surrender. There is a certain comfort in knowing what is real and where things are; to have that comfort stripped away can be rapturous, or distressing. It can even be dangerous. During a Turrell show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1980, several visitors to a piece called “City of Arhirit” became unsteady in the bright blue haze and tried to brace themselves against a wall made of light. Some of them fell down. A few got hurt. One woman, who broke her arm, sued the Whitney and Turrell for more than $10,000, claiming that the show made her so “disoriented and confused” that she “violently precipitated to the floor.” Another visitor, who sprained her wrist, sued the Whitney for $250,000. The museum’s insurance company then filed a claim against Turrell, and although a member of the Whitney family put a stop to the suit, Turrell still gets sore thinking about it. He spent $30,000 to defend himself, but it’s not the money that bothers him the most. It’s the lingering feeling that the work didn’t . . . work.

“On some level,” he told me, “you’d have to say I failed.”

We were at his townhouse on Gramercy Park in Manhattan. Like Turrell’s other two homes, in northern Arizona and eastern Maryland, it was furnished mostly in the Shaker style. The walls were cream, with very little hanging art, and the furniture was all in cherry. Turrell sat at the center of a dining table and began to describe other incidents. One of his friends had taken a tumble at the same Whitney show. “He was just standing there,” Turrell said with a shrug, “and he leaned back and fell.” At a show in Vienna, another visitor took a running start and leapt into a Ganzfeld room, perhaps expecting to land on a bed of pillowy clouds. She smashed into a wall. And then there were the “Perceptual Cells.”

The Perceptual Cells are Turrell’s most extreme work. The visitor approaches a giant sphere that looks like an oversize Ping-Pong ball and lies down on something like a morgue drawer to be pushed inside. When the door is shut, the lights come on, so bright that it’s almost pointless to close your eyes. As the colors shift and morph, you begin to see things that aren’t there, like tiny rainbows floating in space and crisp geometric forms. It turns out that what you’re seeing is the biological structure of your own eye, which, in the blinding intensity, has turned on itself.

Even Turrell describes the Perceptual Cells as “invasive” and “oppressive.” Some of his most avid fans prefer not to see the series. Andrea Glimcher represents Turrell at the Pace Gallery in Manhattan, but when she visited LACMA for the opening in May, she declined to view the Perceptual Cell. “Just thinking about it makes me want to press a panic button,” she told me. When one of the curators of this year’s Guggenheim exhibition, Nat Trotman, viewed the Perceptual Cell at LACMA, he wrote me to say that it had “rewired” his thinking and was “very aggressive and very hallucinatory.” Before viewers climb into the Perceptual Cells, Turrell makes them sign waivers to certify that they are 18 years old, sober and sane.

***

THE JOKE AMONG Turrell’s friends is that, to see his work, you must first become hopelessly lost. Though he is routinely listed among the signature artists of his generation (in 1984, he and Robert Irwin became the first visual artists to receive MacArthur “genius” grants), he has never enjoyed the widespread recognition of artists like Donald Judd, Jasper Johns and Chuck Close. In fact, Turrell has not held a major museum show in New York since the Whitney exhibition of 1980, or in Los Angeles since 1985.

Much of his art is located in the far corners of the earth. There is an 18,000-square-foot museum devoted to Turrell in the mountains of Argentina, a monumental pyramid he constructed in eastern Australia and an even larger one on the Yucatán Peninsula, with chambers that capture natural light.

Turrell’s greatest work and lifelong fixation is an extinct volcano on his ranch in Arizona, where he has been developing a network of tunnels and underground rooms since 1974. The volcano has a bowl-shaped depression on its top and is known as Roden Crater. Turrell has never opened the crater to the public, and he is guarded about who sees it. An invitation to visit Roden is one of the most coveted tickets in American art.

“It has become, even unfinished, as important as any artwork ever made,” Michael Govan said. “I know I’m going out on a limb here a little bit, but I think it’s one of the most ambitious artworks ever attempted by a single human being.”

Turrell’s obsession with the crater is the stuff of legend, but he prefers not to analyze it. For a man driven by such a monomaniacal artistic impulse, he is startlingly uninterested in himself. Through dozens of conversations in multiple cities over perhaps a hundred hours, I found him willing to examine almost any idea, so long as it didn’t require any self-reflection. I would ask, for example, about his place in the art world, or his faith, or lack of it, or how he feels about the crater as he grows older and the forces of obsession and mortality collide — and each time he would nod and frown and say something like, “Well, you know, you just have to accept things as they are.” Then he would launch into a 30-minute dissertation on the geometry of sailboat hulls. The more questions you ask Turrell, the more elusive he seems. Growing up Quaker, he was always being told to nurture “the light within.” At 70, he seems more interested in the light without.

Some of Turrell’s contemporaries view the mystery around him with a measure of envy. One day this spring, I stopped by the studio of Chuck Close in Lower Manhattan. There was a large, incomplete portrait of a woman hanging from one wall, with its lower half descending through a narrow gap in the floor. Close, who has been in a wheelchair since an arterial collapse in 1988, raises or lowers the canvas in order to reach the spot where he’s working. A few years ago, Turrell invited him to visit Roden Crater.

“I was shocked when I got out there,” Close said. First, that Turrell had made the crater wheelchair-accessible. “He proudly put me in this four-wheel-drive golf cart and drove me all the way up into the thing.” But when they reached the top, Close found another surprise. Turrell has spent years shaping the rim of the caldera in such a way that it seems to distort the contour of the sky. He calls this “celestial vaulting,” and he helped Close lie down to experience the phenomenon. Staring up, Close was struck in equal parts by the power of the illusion and its subtlety. “He’s an orchestrator of experience,” Close said, “not a creator of cheap effects. And every artists knows how cheap an effect is, and how revolutionary an experience.”

Close is among the most famous living painters, but when he looks at an artist like Turrell, it sometimes makes him skeptical of his own fame. “It makes me wonder if I’m making pabulum for the masses,” he said with a laugh. Close described how, in the 1960s, artists like Turrell and Robert Smithson and Walter de Maria “wanted to go in the desert and dig a hole or ride a motorcycle in a circle, or dig a ditch, or put a bunch of spikes for lightning to hit. It was about not making a commodity. Not making it something that would go in a gallery.” Many of those artists criticized Close for working in a more conventional medium. “I’ve been arguing with Mel Bochner for years,” he said, “because Mel gave me tremendous grief for making stuff that hung on the wall, like I might just as well have been a prostitute inviting people up to my room.”

Close pointed out with a wry smile that most of those friends have since found a way to show their work. “After a while, they thought, Oh, no one’s going to see this stuff!” he said. “So then they take photographs. Then they frame the photographs and put them in a gallery.” Still, he sometimes wonders if they were on to something back in the ’60s — and if Turrell, in his work at the crater, still is.

“I may be known by more people, but I’m often known for all the wrong reasons,” Close said.

For his part, Turrell has begun to think more about what he’ll leave behind. On a recent drive across the desert to see the crater, he turned to me and said, “I was absolutely going to get this project done by the year 2000, so I’m a little embarrassed by it. There have been periods of euphoria. There have been times that I’ve been discouraged, and times when I’ve just gone out and enjoyed the place — and realized that maybe this would be it. Maybe it wouldn’t get any further.”

***

WE WERE APPROACHING the crater through a field of impossibly picturesque cattle, their long, straight backs and thick conformation the envy of any rancher. Turrell bounced along at the wheel of the truck, smiling at the herd. “We’ve learned a lot about livestock,” he said, “but the biggest thing is learning about personnel. You know, you’re not going to want artists to take care of your livestock.”

When Turrell first spotted the crater from an airplane in 1974, he had no intention of buying the land around it. He just wanted to dig into the volcano. He persuaded the Dia Art Foundation in Texas to purchase the site on his behalf. When the foundation spiraled into financial trouble a few years later, Turrell scrambled to take over the title. He applied for a loan, but the bank told him the ranch wasn’t big enough to turn a profit. “They said, ‘This will just be a gentleman’s ranch, and you’ll lose money,’ ” Turrell said. “Which I now understand is true. They said: ‘But there’s one ranch over that’s now for sale. If you buy that one, and you buy the one in between, we think we could negotiate — we won’t loan you a little, but we’ll loan you a lot!’ ”

Turrell by then was married with young children, and his wife opposed the purchase. “My wife said at the time, ‘You’re mortgaging our children’s future,’ ” he said, “and for that and other reasons, she left — and I took the loan.”

By the time Turrell had signed the note for all three ranches and leased the public land between them, he was the proud, solitary overseer of a 155-square-mile property that could be supported only with livestock. He was 36 years old and had never raised a cow in his life.

Turrell was brought up in Pasadena in a devout Quaker family. “It was like the conservative Mennonites,” he said. “I come from a family that does not believe in art to this day. They think art is vanity.” Even as a child, Turrell was skeptical of the family’s old-fashioned mores. Little things, like his mother’s refusal to use household appliances, bothered him. “My mother did not have a toaster oven and would toast bread in the oven, which I thought was stupid,” he said. “They didn’t do cars and electricity, that kind of stuff.”

One of Turrell’s aunts, Frances Hodges, lived in Manhattan and worked for a fashion magazine. When Turrell visited, Hodges would take him to concerts and museums, expounding upon the virtues of engagement with modern life. “Her whole thought,” Turrell said, “was doing something society would contend with. That was her purpose in fashion. She didn’t care if it was a vanity.” On a trip to the Museum of Modern Art with Hodges in the 1950s, Turrell discovered the work of Thomas Wilfred, who experimented with projected light in the early 1900s. Turrell remembers staring at one of Wilfred’s “light boxes,” in thrall to its shifting lines of shadow and color. Today, his home on Gramercy Park is next door to the one where Hodges lived.

In 1961, Turrell entered Pomona College to study math and perceptual psychology, but on the side, he continued to indulge his interest in art. He took courses in art history and signed up for studio classes. After graduation in 1965, he enrolled in a graduate art program at the University of California, Irvine. That wasn’t to last. In 1966, he was arrested for coaching young men to avoid the Vietnam draft. He spent about a year in jail, and after his release in 1967, moved into a shuttered hotel in the Ocean Park section of Santa Monica. Over the next seven years, he would make a series of artistic breakthroughs that define his work today.

Turrell had discovered a strange optical effect in one of his projects for grad school. By placing a slide projector in an empty room and pointing its beam toward the corner, he found that he could make a cube of light that seemed to occupy physical space. As he settled into the rooms of the Mendota Hotel, he began to explore variations on the idea. Soon he was using colored slides and moving the projector around the room. He discovered that he could make pyramids and rectangles of light, which seemed to lean against the wall or float halfway to the ceiling. After a few months, he switched the bulb from tungsten to xenon, fascinated by the subtle difference in its effect. Over the next five decades, he would become an expert on light-bulb varieties, studying the distinctive character of neon, argon, ultraviolet, fluorescent and LEDs. For his 70th birthday last month, a friend gave him a bulb he’d never used before; Turrell was ecstatic.

By the late 1960s, he was also experimenting with outdoor light. He painted the windows of the hotel and scratched lines in the paint, allowing narrow slits of light to enter the room. He found that he could create patterns and illusions, much as he had with the projector. He called the series “Mendota Stoppages,” and he felt they had at least one advantage over the projection series: Because the light came from outside, there was no machinery in the room. He had created a gallery in which the art was made entirely of light.

Turrell wanted to keep the room empty but fill it with electric light. He realized that he could modify the walls to create hidden chambers for the bulbs. He called these pieces “Shallow Space Constructions” and tried a dozen permutations. In some, he tucked bulbs along a single edge of the room; in others, the whole frame of a wall glowed with brilliant color. One of the earliest Shallow Spaces, “Raemar Pink White,” is currently on display at LACMA. After 44 years, it still has the coruscating radiance of something from a future world.

By the early 1970s, Turrell was exploring another phenomenon with natural light. Instead of scratching paint on the windows, he cut large holes in the walls and ceiling of the old hotel to create a view of the open sky. With the right size of opening and the right vantage and some careful finish work, he found that it was possible to eliminate the sense of depth, so the sky appeared to be painted directly on the ceiling. Then he pointed electric lights at the hole, marveling at the dissonance between the light coming in and going out. He discovered that when he changed the color of the electric lights, he could change the apparent color of the sky. He called the series “Skyspaces.”

Turrell’s studio at the Mendota Hotel had become a locus for artists, curators and gallery owners who passed through Southern California. The founder of the Pace Gallery, Arne Glimcher, offered him a show. Turrell agreed, then changed his mind. The Italian collector Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo stopped in to ask if Turrell would cut a Skyspace into his villa near Milan. Turrell promised to do it soon. All he really wanted to do was stay in the old hotel, cutting his holes and building his walls and bathing in his light. But in April 1974, the hotel’s owners threw him out. A terse note ordered Turrell to “dispossess, quit, and surrender the premises.”

A few years earlier, he had scraped together enough money to buy a small airplane, which he kept in a nearby hangar and maintained himself. He’d also received a Guggenheim fellowship, which gave him some financial freedom. He packed his belongings onto his airplane and took off. For the next seven months, Turrell canvassed the Western skies. Each evening, he would land the plane wherever he happened to be, unfurling a bedroll to sleep beneath its wing. In the morning, he was back in flight, scanning the desert floor. He wanted to find a small mountain surrounded by plains, so the view from on top would resemble that of flight. Inside the mountain, he planned to carve tunnels and chambers illuminated by celestial light. He would bring together all his previous work in a new studio that no one could take away from him.

The day he spotted Roden Crater, he knew it was the one. The land wasn’t for sale, but he persuaded the owner to let it go, and soon he had set up camp at the base of his own private volcano. By day, he traipsed the surface with a pile of surveying equipment, drawing topographic maps to guide his work. At night, he lay on the top and studied the stars. He tried to imagine how he would bring their light inside the mountain.

***

EVEN AT A DISTANCE, it’s easy to see why Turrell stopped at Roden Crater. The silhouette on the horizon is stunning, a topless pyramid floating on a sea of amber grass. As you draw close, the color begins to fill in, piles of deep red and charcoal cinder in heaps around the core.

Over the last 30 years, Turrell’s ranching operation has only grown. What began as a concession to economics has become a private passion. The ranch now spreads across 227 square miles — roughly 145,000 acres — with a black angus herd of nearly 2,500 head. Most are certified “natural” and will produce prime-grade beef. “When you’re O.C.D.,” Turrell said, “you want the most beautiful animals.”

The ranch has also become part of the viewing experience at the crater. In the same way the eye must adapt to darkness in some of Turrell’s museum pieces, the endless drive across the desert prepares a visitor for the singularity of Roden. Distance and isolation come naturally to Turrell, but he has also learned how valuable they are to his work. One of my favorite Turrell pieces is the Skyspace “Tending (Blue),” which is inside a small stone building behind the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas. To reach the piece, you pass through a Renzo Piano-designed building filled with northern light, then you cross the clean, clear lines of a landscape by Peter Walker. By the time you enter the Skyspace, the city of Dallas is long forgotten. I once lost the better part of a day inside, staring up as clouds lofted and flattened against the ceiling. But last year, a mirrored skyscraper went up nearby, reflecting glare into the building, killing plants in the garden and looming into view of the Skyspace. The museum had to close it.

At Roden Crater, Turrell has no such problems. The nearest town, Flagstaff, is home to the Lowell Observatory, and the city government has maintained “dark sky” ordinances since 1958. It is illegal to shine a searchlight in Flagstaff, and it has been for 55 years. In 2001, the city was selected by the International Dark Sky Association as the first “Dark Sky City.” Several years ago, Turrell joined forces with local and Navajo leaders to tighten the laws even further. Currently most of the outdoor lighting in the city and surrounding areas has to be shielded.

We were pulling around the base of the crater and began to climb the side. Halfway up, we turned into the parking area of a small lodge. The lodge is built mostly from local stone and leftover materials from the crater project. There is a small kitchen, a large common area and four bedrooms tucked into the back. Someday, Turrell hopes to build additional lodges and rent their rooms, so visitors can spend the night at the crater.

A few of Turrell’s staff members had gathered inside the lodge, and the curators of the Guggenheim show, Nat Trotman and Carmen Giménez, had flown in from New York. Trotman and Giménez made an amusing pair. Trotman is tall and bulky with a tangle of dark hair, and is so well spoken that he sometimes seems to be reading from a script. Giménez is slight, energetic and impulsive. She is from Spain but speaks English with a French accent. Since 1989, she has been the museum’s senior curator of 20th-century art. The two had been to the crater together once before, in the rain. Now they were back, as Trotman put it, “to still our minds and immerse ourselves in what he’s doing.”

***

TROTMAN REALLY DID wonder what Turrell was doing — for months it had been a mystery. The show at the Guggenheim includes a piece that no one has ever seen. It is also Turrell’s largest installation piece, and one that’s difficult to classify: a 79-foot tower of light in the museum’s central rotunda.

Any Turrell show asks a lot of a museum, but the tower, called “Aten Reign,” is in a league of its own. Nothing quite like it has ever been assembled in the Guggenheim, and neither Trotman nor Giménez could be sure what it would look like.

In simple terms, the tower is made from a series of metal rings, which are spaced 11 feet apart and wrapped in flexible plastic to form a cone. When it has been fully assembled in the rotunda, it will hang from the atrium ceiling, with the bottom edge dangling about 10 feet from the floor. Viewers will walk underneath the cone and look up at a show of light. In a sense, the piece is a Skyspace, because the light may enter through the glass roof; in another sense, it is a Ganzfeld, because the effect will be one of indistinct space and gloaming light. But in truth, nobody knows what it will be, except maybe — hopefully — Turrell.

“When you work with an artist like James,” Giménez said one day as we stood in the center of the rotunda, “the most important thing is to stand aside and make things possible for him.”

Trotman was trying to maintain the same perspective, but it wasn’t easy. While Giménez spent most of her time in Madrid, he was responsible for coordinating the plans and logistics for a huge installation piece that he couldn’t quite imagine. He had drawn renderings of the tower, but they were only speculation. Basic details were anybody’s guess. It was unclear, for example, whether Turrell would leave the atrium window clear, or allow a small circle of light through, or block it off entirely. Whatever light did filter into the piece would change throughout the day, but Trotman had no idea how that would affect the color of the piece. In fact, he had no idea what color the piece would be. He hoped that Turrell would use a series of shifting hues that blurred from one to the next, but he didn’t know if that would happen, and he didn’t expect to know until a week or two before the opening, when the tower was in place and Turrell arrived to light it. When someone asked Trotman about the piece, he would usually shrug and say, “I really don’t know what he’s going to do.”

To build the tower, the Guggenheim fabrication team rented a warehouse in New Jersey, and I joined Trotman there one afternoon for a look. The warehouse was a huge, grimy space lighted with fluorescent bulbs. In the center, the top portion of the tower dangled from hooks on the ceiling. A skin of white plastic was stretched around it, and a small crew of lighting assistants milled about, blasting different colors inside. Turrell’s chief lighting expert, Matt Schreiber, stood below, looking up into the cone. Periodically, he would call out instructions, like, “Can you make it cold white, and then start bringing it down?” or, “You know, the easiest is red — when in doubt, make it red.”

Trotman stood to the side. During a pause, he approached Schreiber and asked, “Do you have any way to know how bright it’s going to be?”

Schreiber shook his head.

“You know,” Trotman said, “depending on what time of day it is, the light is going to change.”

“Yeah,” Schreiber said. “If we have time, we could make a night setting.”

Trotman smiled. “That would be good,” he said.

Schreiber called out, “Make it blue,” and stepped to the center of the ring. He turned to an assistant and said, “This other blue, when you look at it next to a normal blue, looks white.”

Every curator who has worked with Turrell has been through an experience like Trotman’s. It was a story I heard in museums and galleries all over the country. Richard Andrews, who ran the Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington for 20 years, told me about his own introduction to Turrell. It was 1981, and Andrews was a young artist himself. Like many artists, he was distressed that the galleries in town were not showing much contemporary work. He and his friends decided to rent an exhibition space of their own. It was a cavernous three-story warehouse with unfinished interiors, and on a whim, they asked Turrell to open their first show. To their shock, he agreed.

Turrell flew up to Seattle and began to help renovate the warehouse. He put together a list of pieces he wanted to show on the first floor, but as the months ticked past and the opening drew closer, he still had no plans for the upper level. “I kept saying to him, ‘So, what are you going to do?’ ” Andrews recalled. “And he basically, for months, said, ‘I don’t know.’ ”

Finally, with only a couple of weeks remaining, Turrell had an idea. He asked the group to help him build a wall in the center of the room with three large rectangular holes. Then he climbed through the holes and began to hang fluorescent lights on the back of the wall. Andrews and his friends watched. They had no idea what Turrell was doing — until at last he turned off the main lights and flipped on the ones he had installed. The rectangular windows exploded with brilliant light: an ethereal pink on the left, and a deep blue on the right, and in the middle a mélange of both colors that Andrews still can’t quite explain. “I can really only describe it as fog,” he said. “These two extraordinary colors moved toward each other and through each other, and it was just crazy.”

Today Andrews serves as the president of Skystone Foundation, a nonprofit organization that Turrell created to manage Roden Crater. One big part of Andrews’s job is to raise enough money to finish the crater. Finding donors in the recession has been a daunting task, so Andrews has spent the past five years preparing for a future drive. One of the first things he knew he would need, if he wanted to raise several million dollars, was to know exactly what “several” means. When you’re trying to solicit large amounts of cash, it’s helpful to explain where the money is going. Earlier this year, Andrews and Turrell completed the first full set of blueprints for the crater — detailing every screw, bolt, rod of reinforcing bar and cubic yard of concrete that the project will take.

Now that Andrews has the blueprints, he can estimate the costs; what remains is to grab the attention of the public and donors in a way that Turrell never has before. With so much of his work scattered across the globe, it can take years for a potential fan to discover Turrell. Even the best photography doesn’t begin to capture the immersive experience. For those inclined to travel for art, the exhibitions this summer present the first opportunity to take in so much of his work at once. For Turrell, what his newly raised profile allows, maybe, is a chance to complete the crater, his life’s work.

***

THE AFTERNOON SUN was beginning to descend over Roden, and we left the lodge and followed a short path to the main entrance, a pair of high metal doors. As we stepped through, it was instantly apparent that none of my expectations had been right. For one thing, the room was several times larger than I had imagined. For another, it was as perfectly finished as the most elegant Midtown hotel.

We were in a circular room, with a slightly convex top, that Turrell calls the Sun and Moon Space. At the center of the room, a massive sheet of black stone rested on its edge. An eight-foot-diameter circle had been cut from the center and replaced with white marble. The seam where the two colors met was perfectly flush. One side of the slab faced the doors where we entered, which was precisely the direction of the rising sun at summer solstice. The other side faced the opening of a long tunnel, which rose gently into the distance. This was the direction of the moonset at its southernmost point in the lunar cycle. Every 18.61 years, the moon would align perfectly with the center of the tunnel, and Turrell had installed a five-foot diameter lens at the midpoint to refract its image onto the white circle. The next such occasion would be in 2025.

One by one, we walked up the tunnel. It was 854 feet long and 12 feet in diameter, with blue-black interior walls and ribs protruding every four feet. At the top, a great white circle of light beamed toward us. Or so it seemed. As we drew closer, the color changed from white to blue, and the shape began to shift, elongating from a circle to an oval and rising overhead, until it was clear that what had seemed to be a round opening at the far end of the tunnel was in fact an elliptical Skyspace in a large viewing room. A long, narrow staircase made of bronze ascended through it.

We climbed onto the top of the crater and stepped into the sun. Once again we were surrounded by a Martian landscape of crushed red stone. A cold wind blew across the caldera, and we lay down to view the sky, the clouds streaking overhead as the heavens vaulted.

Dusk was coming. We got up and followed a narrow ramp into another Skyspace. It was round, with a narrow bench around the perimeter. Turrell calls it “Crater’s Eye.” We took seats on the bench and stared through the opening in silence. The color of the sky was deepening. It was rich with blue and darkness. It seemed to hover on the ceiling close enough to touch. No one spoke for 30 minutes. I glanced over at Turrell. His hands were folded in his lap, his eyes smiling at the sky. Whatever else the crater had become for him — a job, a dream, an office, a persistent reminder of his own mortality — it was clear that the Skyspace still had the power to lift him up from earth.

When the last hint of blue had vanished into night, Turrell and the others wandered outside. Trotman and I crept back into the crater. We passed the bronze staircase, glimmering in darkness, and we turned down the long tunnel toward the Sun and Moon Space. The white disc at the bottom glowed with ambient light, and Trotman walked toward it like a man in a trance. He disappeared from view. I stopped for a moment to stare down the tunnel. Then I turned around to face the sky through the ellipse. Something flashed at the corner of my eye and I glanced up. There was a tube of white light hovering in the air above me. It was thick and sturdy and looked as though I could grab it and climb into the stars. It streamed down the tunnel to the gleaming stone.

Back at the lodge, I took a seat beside Turrell at a table made of plywood. A few of his friends from town were preparing a dinner of beef from his ranch, and Turrell had brought several bottles of wine from another friend’s vineyard. They all were whispering excitedly about what they’d seen. Turrell sat silently and sipped his wine. He didn’t ask what I thought of the crater, and I didn’t volunteer. It seemed as if we both knew that it was better not to say. The crater was perfect, and incomplete, and his time to finish it was winding down.

“You know,” he told me earlier in the truck, “I’d like to see it myself.”

Wil S. Hylton is a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine and the author of Vanished. His complete archive is available on Longform.