LONGFORM REPRINTS

This article originally appeared in Esquire and is reprinted on Longform by permission of the author.

“COME ON IN HERE,” an FBI agent grumbled near the end of that piercing winter. It was the first Sunday in March, last year, and Wen Ho Lee was in for more questioning. He had already been interviewed on January 17 and February 8 and 9. On February 10, he had met FBI agents in a hot Albuquerque hotel room, where he sat for six hours taking a polygraph test with the questioner standing behind him. On March 5, he had been summoned to the FBI’s branch office in Santa Fe, and now, two days later, he was back again. “Can you give me just verbally,” Lee asked, “what is the important part related to me?” His English was far from perfect, but he had been forbidden to bring a translator. “The important part,” Special Agent Carol Covert explained, “is that there is a person at the lab that’s committed espionage, and that points to you.” Lee was confused. The agents had told him it wasn’t necessary to hire a lawyer just yet, and he wanted to cooperate. “But do they have any proof, evidence?” he wondered. “You know, Wen Ho,” Covert replied, “Washington has a bunch of facts, and the facts are this: In 1988, you went to China.” It was true. It was also true that Lee had been to China in 1986. But this was hardly news. He had filed trip reports with the lab both times, listing the names of everyone he met there. “If you want me to swear with the God or whatever, okay, I can swear if that’s what you believe,” Lee insisted. Covert pressed on. “Do you know what’s in the package that I got today? You failed your polygraphs.” It wasn’t true, but Lee didn’t know that yet.

“How do you know I fail?”

“I got it right here!” Covert shouted, showing Lee an envelope.

“I don’t know why I fail. I have not done anything. I never give any classified information to Chinese people.”

“You know, Wen Ho, pretty soon you’re going to have reporters knocking on your door. They’re going to be knocking on the door of your friends. They’re going to find your son, and they are going to say, ‘You know your father is a spy?'”

“But I … I’m not a spy.”

“But Wen Ho, something else must have happened for you not to be able to pass these polygraphs.”

“I don’t know.” He paused. “I don’t know about the … the law.”

“You’re gonna learn real quick when they come and they knock on your door and they put a pair of handcuffs on you, Wen Ho! Do you know how many people have been arrested for espionage in the United States?”

He didn’t. “I don’t pay much attention to that,” he said.

“Do you know who the Rosenbergs are?”

“I heard them, yeah.”

“The Rosenbergs are the only people that never cooperated with the federal government in an espionage case. You know what happened to them? They electrocuted them, Wen Ho.”

“Yeah, I heard.”

“They didn’t care whether they professed their innocence all day long. They electrocuted them, okay? John Walker! Okay, he’s another one. That’s going to happen, Wen Ho. What are you going to tell your son?”

“I will open a Chinese restaurant….”

“You’re going to be in jail, Wen Ho. And your kids are going to have to deal with that the rest of their lives, people coming up to them saying, ‘Hey, isn’t your dad that Wen Ho Lee guy that got arrested up at the laboratory?'”

“I know what you mean, and I know exactly what the consequence. However, I already told you the truth, and I don’t have anything better than the truth.”

“You know what? The Rosenbergs professed their innocence. The Rosenbergs weren’t concerned, either.”

“Yeah.”

“The Rosenbergs are dead.”

***

GUILTY. That’s what he said to the judge eighteen months later, standing there in his gray suit and his white shirt, in his blue tie, looking tired. “Guilty,” he said, or, rather, he pleaded, but it was a plea without remorse.

He had been in jail for nine months by then, in the bright loneliness of solitary confinement, and he had lost weight there, fifteen pounds, thinking about the evidence against him. Not the evidence they had brought at first, because at first they hadn’t brought any evidence. It was the evidence they found along the way. That was the damning stuff. For nine months, he had been thinking about that. Nine months, he had not seen the moon.

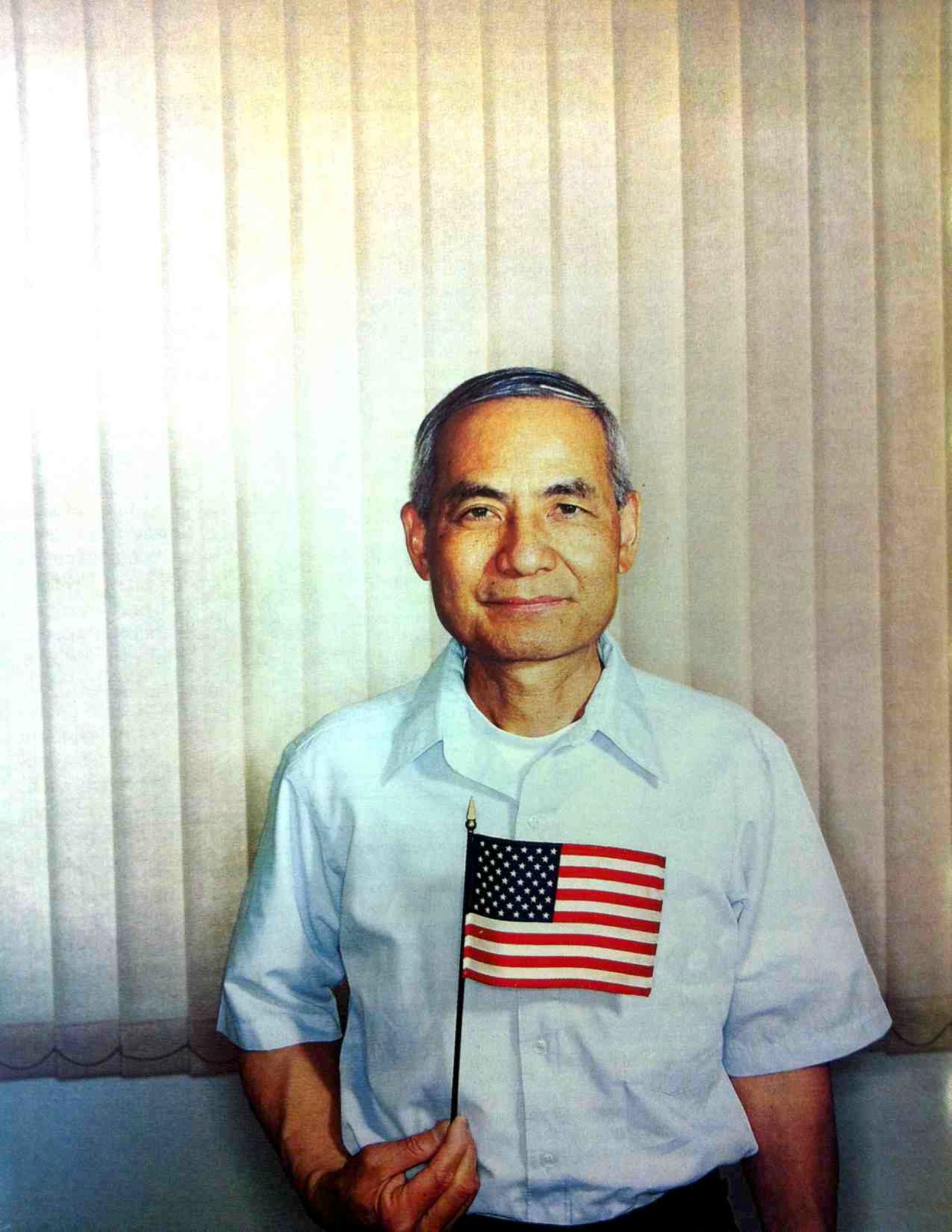

Guilty, he said, to walk away from it all, out into the sunlight with his wife. Guilty, to be with his family, even without his rights. Without his right to vote or his right to bear arms or his right to serve on a jury. Rights he had studied and earned in his citizenship class many years ago. Guilty, he said, exchanging those rights for the stark New Mexico sky.

Nine months, 278 days, with his wife at home alone, until with that one word, he brought it all to an end. There would be no more charges or pleas. But still, it wasn’t neat, wasn’t tidy, the way he liked things. Because, yes, he was guilty of a security breach, and, yes, this breach was a crime. But he knew of more guilt, guilt bigger than his. Guilt that his own guilt would conceal.

***

IT BEGAN, ironically, with a leak from China. In 1995, a Chinese secret agent strolled into CIA offices with a seventy-four-page document from the Chinese nuclear program. If, at first, the leak seemed like a triumph for the CIA, it didn’t seem that way for long. Because the document contained a blueprint for an American nuclear bomb. Specifically, the “walk-in document,” as it was called, described the W-88 ballistic missile, one of the most sophisticated warheads in the U.S. nuclear arsenal. When the CIA reported this news, investigators at the Department of Energy were ordered to start hunting for the mole.

Unfortunately, there were thousands of possible suspects. The W-88 had been designed in the late seventies by a small group of scientists at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico (LANL–employees call it “Lanel”), but over the next fifteen years, the blueprint had been passed through countless hands at the Department of Defense, then on to private contractors like Lockheed Martin, where some of the parts were made. With such a broad field of potential suspects, the DOE investigation threatened to move slowly, so investigators decided to focus their search on the Los Alamos lab.

That may have been a mistake. “This information could have come from many places,” says Robert Vrooman, who was the chief counterintelligence officer at LANL until his retirement last year. “The Department of Defense only requires a $65 criminal-records check for access to nuclear-design information. Where would you say the weakness is in the system?” But DOE investigators ignored the Department of Defense and decided to concentrate on the lab. “They had no clue how the process of designing and putting a nuclear weapon into the inventory worked,” Vrooman says. “I did introduce them to a senior nuclear-weapons person who tried to explain the process, but it did not stick. They seemed to think that if the W-88 was designed at LANL, it had to be compromised at LANL.”

Once focused on the lab, DOE investigators identified the basic criteria for their search. The spy, they concluded, would be someone with access to the W-88 blueprint, who had been to China between 1984 and 1988, and who had spoken, at least once, with visiting Chinese scientists. These criteria did little to narrow the search. In truth, the lab actively encouraged its employees to visit with Chinese scientists, and over the course of two decades, those visits had provided more insight into the Chinese nuclear program than any other source, including the CIA. So it wasn’t surprising when the DOE’s “matrix analysis,” as it was called, turned up seventy Los Alamos employees who had visited China during the specified years. In fact, there may have been even more. “They missed a large group,” says Vrooman. “The list of seventy should be about eighty-five. From that list, they narrowed it down to twelve who were supposed to have access to the W-88, but the list of twelve really contained people who had no access and, in one case, no security clearance. To make this even more puzzling, there were people on the list of seventy who should have been on the list of twelve but were missed. All in all, this was a sloppy investigation.”

Vrooman expressed his concerns about the investigation as early as last May. “Ethnicity was a crucial component in identifying Lee as a suspect,”he wrote in a letter to Senator Conrad Burns. “Caucasians with the same background as Lee were ignored.”

Once Lee had been singled out, the FBI began to watch him, bringing him in for interviews and polygraph tests. During the last of these tests, on February 10, investigators asked him, “Have you ever unlawfully transmitted classified information to a third party?” Lee’s response was no, and, according to the polygraph results, he was telling the truth. But FBI agents remained suspicious, bringing Lee back to the FBI office without a lawyer or a translator, saying that he had failed the polygraphs, comparing him to Julius Rosenberg, threatening him with electrocution.

The day after those threats, Wen Ho Lee started looking for a lawyer. But still he told his family not to worry. Here, he told them, innocent people are safe. And when, a few days later, the FBI parked an assortment of cars and agents outside his house for twenty-four-hour surveillance, Lee tried to demonstrate his goodwill, bringing them hot green tea and fresh fruit, wanting to seem unafraid. Some days he would even show them a good time, packing up his fishing gear and driving across the desert, up into the nearby Sangre de Cristo Mountains, where he would hike by the river with the agents behind him, all laughing and chatting together, keeping an eye on Lee as he fished for trout.

When some of those agents came to his door with a search warrant on April 10, Lee let them in, then went outside to prune the apple tree while they rifled through his belongings. His next-door neighbors, the Marshalls, saw the search team enter, and they called out, alarmed, but Lee wandered over and told them, No problem. He had known Don and Jean for twenty years, and he didn’t want them to worry. Their kids had grown up together, roller-skating, making sand castles in the backyard, and learning piano from Jean. They often saw one another while they worked in their gardens, and Wen Ho would always come to the fence to tease the Marshalls. “Why do you waste your time growing flowers?” he would ask, his eyes creased with smiles. Then he would hand them fresh peas and cabbage and walk back to his crops, chin high. Even at work, in the laboratory’s top-secret X division, Wen Ho and Don would hang out sometimes, sitting in Don’s office, telling jokes and swapping stories about their kids.

Of course, nobody at the lab, including Don, knew what to expect when the FBI came to search Lee’s office in March, but it seemed possible, maybe even probable, that they would find something. With so much classified information lying around, it’s easy to make a mistake. It happens. Or it can. You just set the wrong piece of paper on top of the wrong stack, then file it in the wrong drawer, or you save a computer file incorrectly, or you forget to destroy a memo. Mistakes like this are common, and they seemed especially possible for Wen Ho, who was known as the office pack rat, with his nearly endless supply of data organized in looseleaf binders, all labeled and jammed into a pair of six-foot-tall bookshelves in his office. But it also seemed reasonable to expect that if investigators did find something wrong, Lee would be scolded in the usual fashion, with a slap on the wrist or a written warning. After all, this wasn’t China. It wasn’t even a military lab.

***

AT FIRST, the Los Alamos National Laboratory was a government facility, a hasty military operation undertaken at the behest of Franklin Roosevelt. After learning from Albert Einstein that the Nazi government was splitting atoms and that the process, known as fission, could be used to build a superbomb, Roosevelt ordered the Pentagon to open a fission laboratory.

The site the Pentagon chose for the lab was at the top of a mesa about twenty-seven miles from Santa Fe, where nobody ever went. There had never even been a town there, just a small prep school that doubled as a meeting place for Boy Scout Troop 22. In January 1943, the school held an early graduation at the Pentagon’s request, then abandoned the site to make room for a team of Albuquerque construction workers. For the next two years, the lab would be officially nothing more than Post Office Box 1663, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The first big problem with the lab was that nobody wanted to work there. Most of America’s best scientists worked at universities, where they enjoyed liberal funding and little oversight. Few were willing to make the transition to a military facility. So in February 1943, facing a personnel crisis, Pentagon officials got creative. They approached the University of California with an offer: If the UC Board of Regents would take nominal control of the laboratory, handling paychecks, traveling expenses, and sundry administrative duties, the Pentagon would agree to provide the university with an annual (padded) budget.

The fine print of the proposal, however, revealed that the university would not be involved in much of anything other than lending cachet. UC administrators would not manage the day-to-day affairs of the lab, would not even know its purpose or location. In this arrangement, the lab would exist in a netherworld, officially an academic site but funded by the government, with oversight from neither. Some members of the UC Board of Regents recognized that the deal was a sham; as the regents’ secretary put it bluntly, “It very definitely seemed to be that the university, as a corporation, was to be almost a straw man in the proceedings.” But when Pentagon officials vaguely explained that the lab would contribute to the war effort, the regents’ secretary conceded, and the UC board agreed to manage the labs as an act of “public service.”

It was a relationship born of wartime necessity, and, strangely, the same hands-off management exists today. But in the early years, it did the trick–with UC at the helm, a slew of top scientists filled the laboratory. By January 1944, the lab had thirty-five hundred employees, and a year after that, fifty-seven hundred. Many scientists were disgruntled to discover, on arrival, that their homes were equipped with coal stoves, that their families would share bathrooms with other families, and that, in some cases, more than one family would bunk together in a single room. But they understood that this was only a temporary facility with a singular goal: to build the world’s first nuclear bomb, a device they called the Gadget.

***

LIKE SO MANY things in physics, the nuclear bomb is a fairly simple concept that becomes murky and bizarre in the details. In broad strokes, a nuclear blast is the combination of fission and fusion, fission being the process of splitting atoms apart and fusion the process of bonding them together.

To build a modern nuclear bomb like the W-88, you start with a hollow sphere made of plutonium, twelve centimeters in diameter. Then you inject the sphere with D-T gas (a combination of deuterium and tritium) and surround the whole thing with high explosives. To detonate it, you ignite the explosives, crushing the plutonium sphere and causing it to reach critical mass. At critical mass, the plutonium atoms begin to split, or fission, and each fissioned atom releases a charge of energy as well as two loose neutrons. The loose neutrons–supplemented by a device called a neutron initiator–cause even more plutonium to fission, starting a self-sustaining chain reaction. As an increasing volume of plutonium fissions, accelerating at an exponential rate, the energy created by the process charges the D-T gas until the deuterium and tritium bond. That’s fusion, which releases even more neutrons, causing even more plutonium to fission. By the time all this fissioning ceases, the sphere is awash in neutrons and energy, which bombard a compound called 6LiD, freeing even more D-T gas. Unsurprisingly, with all this energy swirling around that gas, the new deuterium and tritium atoms bond, forming a secondary stage of fusion, a giant sphere of light that rises into the sky, then bursts into a forty-thousand-foot mushroom cloud.

And, if you’re lucky, it never happens again.

***

WEN HO LEE WAS five years old when Los Alamos scientists tested the Gadget. He lived in Taiwan, a Japanese territory, where food was rationed grudgingly. Every day, a Japanese soldier would enter the Lee house to see what the family was eating. Figuring that the youngest in the family would be the least likely to lie, the soldier would point a gun at Wen Ho’s head and ask, “How many bowls of rice have you eaten today?” Wen Ho was smart, and he always said, “One.”

The food rationing ended in 1945, when the fruits of LANL hit Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But no sooner had the Japanese army retreated from Taiwan than the Chinese nationalists moved in. The nationalists were barely more welcome than the Japanese, and in the year that Wen Ho Lee was seven, many Taiwanese were slaughtered in an unsuccessful revolt. Two years later, the nationalists were overthrown by communists on the mainland, and the nationalist leader, Chiang Kai-shek, fled to Taiwan, bringing his troops and his followers with him.

From the start, the United States government supported the nationalists in Taiwan, parking a fleet of warships just off the coast. In spite of any lingering resentment toward Chiang Kai-shek, most Taiwanese were grateful for the U.S. protection. But by the early sixties, with the mainland still launching attacks, many islanders had become frustrated with all the years of struggle, and in 1965, armed with a bachelor’s degree and a passport, Wen Ho Lee left his country. His parents were both dead, and the future in Taiwan looked unpromising. It was time to find another home.

In America, Lee aspired to stability, earning a master’s degree in 1966, then a Ph.D. in 1969, getting married, fathering children–a girl, Alberta, and a boy, Chung–and becoming, in 1974, a naturalized U.S. citizen. By 1980, he had established the most American of lives, building a house in White Rock, just two miles from the lab, and starting a career at the UC facility, worlds away from the violent nationalism of his homeland.

***

A LOT HAD changed in nuclear design by the time Wen Ho Lee joined the lab. For one thing, in the early days, there had been no computers, just a room full of women with calculators. By 1978, though, the entire process had been computerized, and the backbone of the operation was in codes. There were codes for everything. Codes to describe the physical properties of plutonium. Codes to calculate how uranium and tritium would react to shock waves. Codes to describe what each bomb looked like. Codes to specify where each part on the bomb was placed. There were even codes to simulate nuclear explosions. By 1992, those simulated explosions had replaced actual testing, which had been phased out over a period of thirty years by a series of test-ban treaties. And with the increased role of computer simulations, code development was at the forefront of the lab’s scientific mission.

Wen Ho Lee was a code developer. He wrote codes, fine-tuned codes, sometimes corrected codes. Specifically, he dealt with codes that describe the effects of extreme heat and pressure on raw materials like plutonium. The trouble with codes, though, was that a body of work could be erased with a few errant mouse clicks. That happened sometimes at Los Alamos. Files were lost, networks jammed. Lee had personally lost more than his share of files on the faulty computer network. Once, when the automatic backup system malfunctioned, he lost a year’s work. After that, the lab administration issued a memo asking employees to back up their work independently on tapes and disks.

When the FBI shut down the laboratory to search Lee’s office in April 1999, agents paid special attention to his computer. In fact, they performed the most exhaustive computer-network analysis in the history of the FBI, searching through four terrabytes of information, or about one million files. They were looking for evidence that would tie Lee to the walk-in document, something to show that he had given the W-88 blueprint to the Chinese. In the course of their search, however, something else turned up.

According to his computer records, Lee had downloaded 806 megabytes of information from a classified computer onto ten portable tapes in the mid-nineties. Strictly speaking, that wasn’t illegal. Lee had Q clearance, which was more than sufficient to make tapes of nuclear codes. What was illegal was the way he had made those tapes, by manipulating the classification system. He hadn’t downloaded the files directly from the secure computer onto tape. Instead, he had illegally declassified the files, moved them to an unsecure computer, and made the tapes from there.

It would have been far less time-consuming to back up his files the legal way, to make the tapes directly from his classified computer. But Lee couldn’t do that. His classified computer didn’t have a tape drive. So he copied the files onto tape the only way he could. In the process of doing so, he saved those files onto an unsecure computer, and he never bothered to cover his tracks. For the next four years, those files sat undetected on the hard drive of that unsecure computer. It was only when the FBI began to question Lee that he went back to that computer and frantically erased the files, leaving the ghost record that investigators found.

A government expert who later testified against Lee said the tapes he downloaded contained a “chilling collection” of nuclear information. Lee’s colleagues in the X division disagree. To regular folks, 806 megabytes (about the size of three large Zip disks) might seem like a lot of information. But as one code developer in the X division told me, “In the world of computing, it really wasn’t that many files. There may be thousands of files associated with a single operation.”

Other code developers in the X division insist that the collection was more typical than chilling, pointing out that it was the method of downloading, not the content of the tapes, that was illegal. “Every code developer who’s serious and has worked for five or ten years would have exactly that kind of backup,” another X division code developer said. Lee said that’s exactly what his tapes were:backups that he destroyed when they were no longer useful.

After searching Lee’s office and home, the FBI found no evidence to the contrary. Nothing to suggest that he was a spy. Nothing to suggest that he had sent the tapes overseas. Nothing to suggest that he had so much as shown them to another person. Nothing to suggest that he had done anything other than be careless in backing up his work. Still, when news of Lee’s misbehavior found its way to Washington, the Senate held a special hearing at which charges of espionage were hurled relentlessly. Speaking to the assembly, Senator Frank Murkowski said, “It appears that he simply took the access off the classified computer and walked home with it and put it in FedEx and shipped it over to Beijing.” To which Senator Pete Domenici added, “A lot of them that came over here right from China mainland, they come over here and they get their degree, maybe even a great post-doc experience, and then they cheat the system.”

***

THEY CAME TO arrest him one December day, put him in handcuffs, threw him in a car, and bustled him off to prison. This was a federal investigation, and it called for a federal prison, but there are no federal prisons in New Mexico, so investigators brought Lee to a private jail, where he was placed in a solitary-confinement cell, where he spent twenty-three hours a day. Where he had a tiny window, a toilet, a sink, and bunk beds, one empty. Where an FBI agent checked up on his movements every fifteen minutes. Where the screaming of other inmates kept him up at night. Where he was forbidden to keep earplugs or a Walkman to block out the noise. Where he was prohibited from receiving mail, where he was denied access to the news, and where, for the first two weeks, the lights were kept on around the clock. Where he couldn’t take a shower. Where he spent his sixtieth birthday alone, without a celebration, without his family, without the cards his friends had sent him. Where his family could visit once a week, and where, during those visits, he wore shackles on his ankles and handcuffs attached to a heavy belt around his waist. Where, in those shackles, he had to speak to his family by crouching over his chair, stretching his chains to reach the speaker button on a Plexiglas window, leaning awkwardly to get his mouth close to the speaker without falling over. Where FBI agents looked on without comment as the sixty-year-old contorted himself. Where, in that position, he could speak to his family only in English, a language his wife had never mastered. Where he would go to the courtyard for an hour each day and jog in his ankle chains. Where, after three weeks, when some of the restrictions were lifted, he was allowed to receive books through the mail but where he could keep only one book at a time and where, when he wanted another book, he could ask only for “a book,” not the particular book that he wanted. Where he was fed bologna sandwiches, a food he could not eat, thanks to the colon cancer he had beaten ten years earlier. Where, with so little to eat, he lost 15 of his 130 pounds in the span of a month. Where he purchased from the jail commissary a pen and a few notepads, made his top bunk into an office, and wrote a book on mathematics. Where he entertained himself by remembering classical music until, by a judge’s order, he was allowed to get a Walkman, and where he listened to that Walkman, lived by it. Where he hoped each day that his daughter was safe but knew that she was not.

***

ALBERTA LEE WAS never like her brother. Never too popular or athletic or school smart. Chung was Mr. Perfect, best at everything: soccer, math, voted class president, most likely to succeed. Alberta had a sticker collection, listened to Bon Jovi, watched Three’s Company. She loved when her mom would take her shopping at the mall and let her eat fast food on the way home.

By the time Alberta graduated from UCLA, she was ready for a taste of real-life independence, and she took a job with IBM, got a cell phone, a nice apartment in North Carolina, and a steady boyfriend. It was a good enough job, a good enough life, and it made her dad and mom happy.

Things were looking solid until, out of the blue, her dad called, saying something about FBIinterrogations and surveillance. FBI?Surveillance?She tried to warn him, saying, “Dad! At least get a lawyer!” But he wouldn’t hear of it. “Why should I?” he asked. “I haven’t done anything wrong.” Typically out of touch. So he let it get out of hand, and before she knew it, she was reading a story in The New York Times saying he was a spy. Yeah, right, she thought, like my weirdo dad could do something like that. The newspapers didn’t know him. She wanted to tell them, “He’s Taiwanese, dude.” She wanted to tell them he was an American now, innocent until proven otherwise. So one day, just after her father was denied bail, Alberta stood on the steps of the Albuquerque courthouse, and the media gathered around, and she made a little statement: “My family and I love my father. We stand by him and will support him through this.” Better than the alternative, she thought, meaning better than nothing. Her mom was too shy to deal with the prying media, and her brother was wrenching his way through medical school.

Pretty soon, Alberta was doing PR like crazy. Invitations to speak every weekend, at Harvard, in San Francisco, at Annapolis. Newspaper and TV interviews, rallies and fundraisers. Crazy. Like owning a small business on the side, one with too many customers. She spent forty hours a week at her real job, then another forty to sixty on the road, doing the heart’s work, the instinctive work, the work she couldn’t not do. Because there were things she wanted to get across, like, They have no evidence my father’s a spy, like, They’re keeping him in solitary confinement, like, They lied to put him there.

Because she had been there in court when the lead FBI agent swore that her father failed his polygraph test. She had been on the phone with her father’s attorneys when they got hold of those test results. She had seen the results herself and had seen that the scores were high. She had been in court the day the FBI agent returned to the stand to say, “I provided inaccurate testimony.” And she had been shocked then, not just by the false testimony but by the fact that it changed nothing. The fact that her father remained in jail.

So Alberta remained on the road, speaking, meeting, pleading, not sleeping, her task growing harder each day. Harder to speak without lapsing into sobs, and she did sob sometimes, onstage, at rallies, even during interviews. Couldn’t help it and didn’t care anymore. The whole thing was wearing her down, making her crazy, making her furious. Hate mail and threats coming to her mother’s house. Her father thin and pale. It became her personal challenge to recover her father’s good name, and before she lay down for five hours’ sleep each night, she’d ask herself if there was any more she could do. She could feel it taking a toll on her, but it was the first time she had ever been so sure of anything, the first great sacrifice she was willing to make.

***

IT WAS NO coincidence that Lee’s neighbors were outraged by his arrest. Most of his neighbors in White Rock were either employees of LANL or relatives of employees, and they knew what happened inside. Almost everybody slipped up at the lab sometimes, mishandled a code or a document, took a shortcut here or there. Lee had done it, but so had many of them, and most of the time nobody noticed, because nobody was paying attention. At least, nobody in a position of authority.

Really, there wasn’t any authority. The University of California was still technically responsible for management at LANL, and in the years since World War II, the university had also assumed responsibility for the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. But that didn’t mean that UC had ever been an active manager of the labs. In fact, according to the university’s own internal reports, it had been negligent for a long time. The first report came in 1969, when the UC academic senate convened a special committee to review lab management. The committee’s conclusion was clear: “Administrative interaction between the laboratories and the university is barely discernible,” it said. “The university plays the part of a benevolent absentee landlord. It extends its protective shield over the laboratories and allows them to go their way. Aside from trivia, such as stationery with the university’s letterhead, university citations for meritorious service, university paychecks and the like, the presence of the University of California is in no way manifest either at Livermore or at Los Alamos.” In conclusion, the report added, “The laboratories, therefore, exist in a world of their own.”

Nine years later, there had been no changes. So a second committee came together in 1978 and suggested that, for reasons of national security, the university should either pay attention to the labs or stop pretending to manage them. A “reason against continuing the university’s contract with the federal government stems from objection to the secrecy that surrounds nuclear work,” the report stated. “Academics and others have grown increasingly wary of governmental secrecy. It is suspected of being used to cover a multitude of wrongs, from charlatanism to incompetence.”

Eleven more years, still no changes. When a third committee convened in 1989, the members found even less to applaud. “University oversight of the laboratories has been far from satisfactory,” the report said. “A request from the national government to continue to operate the laboratories is not, in and of itself, a sufficient justification for doing so.” Finally, the report recommended, “The university should, in a timely and orderly manner, phase out its responsibility for operating the Lawrence Livermore and Los Alamos National Laboratories.”

Seven years later, still no changes. In 1996, yet another internal-review committee took the university to task. “It is clear that UC does not actually manage the laboratories,” the committee wrote. “Instead, UC delegates to the laboratory directors the authority to define programs and negotiate their costs.”

If the University of California was critical of its own man-agement practices, external reports were even more scathing. A June 1999 review by the President’s

Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board accused the labs of “the worst security record on secrecy that the members of this panel have ever encountered.” Among a litany of criticisms, the board’s report cited a “lab security-management-reporting system that led everywhere but to responsible authority.” In the end, the board’s assessment: “Reorganization is clearly warranted.”

Many LANL employees agree, saying that the lab’s virtual autonomy has led to rampant security breaches. In the course of preparing this story, I spoke with several employees of the X division who admitted to the same infractions as Wen Ho Lee. Some admitted downloading even more information than he had; others confessed to illegally declassifying files. “A lot of people, including me, have declassified classified files,” says Chris Mechels, who worked in the X division with Wen Ho Lee until 1994. “In my whole section, we routinely violated security. People at Los Alamos treat classification as an inconvenience, not as security. Security is a joke. Wen Ho just did what he had to do to make his backup tapes.”

***

WHEN HER HUSBAND was home, Sylvia Lee drank soy milk nearly every day. Because Wen Ho made it fresh, the old way, the way Wen Ho did everything. He would soak the beans in a pot for hours, until they were swollen and soft, then he would skim away the floaters and drive the rest through a screen, adding just the right touch of water, so it came out silken and not too sweet, almost transcendently light.

That’s how Sylvia’s husband was. Exhaustingly precise, but worth it. He spent his evenings and weekends in the garden, crouching over his snow peas and asparagus, and as he stooped there in his T-shirt and his floppy hat, he would envision the meal he would make from scratch. Sylvia and the children joked that Wen Ho was stuck in the past, with his tastes for Schubert and Goethe, with his distastes for microwaves and power mowers, but the old traditions were a part of him, as he was a part of them.

And so, before all this, when the kids were young and they played in the sandbox out back, splashing the dunes with a garden hose, Sylvia felt proud of her life, this life that they had made from nothing. The happiness they had found in America. Wen Ho’s job with good benefits, the community of White Rock, and friends like Don and Jean. All those mornings when she’d stood with Wen Ho as he washed the children’s faces before driving them to school, before they grew up, before they left Sylvia and Wen Ho with this time together, this time to spend enjoying their memories. But those memories are fading now, nine months gone, as Sylvia sits at home on a hot afternoon in her pink-and-white-checkered summer dress, her hair pulled aside in two thick ponytails, her feet snug in fuzzy slippers, her soft, round face without expression, watching television for news of her husband. Watching as she has watched for weeks and months, hoping he will find a way home. Watching as the anchor banter trickles through the room, through the window, to the sidewalk, into the open heat, piercing the silence of the empty desert. Silence in the garden, silence on the patio, silence even throughout the house, in the red-tile hallway strewn with flip-flops, her husband’s and her children’s house shoes, all empty, all waiting with Sylvia Lee, waiting for her husband to come home.

***

THE LAST TIME Sylvia saw him free, she was younger inside. Three times he had been up for bail, three times it was denied, with prosecutors warning the judge that Sylvia’s husband posed an imminent threat to the nation, that he could not be released, not even for one day, not even under FBI surveillance.

And then, suddenly, those same prosecutors offered her husband a deal: If he would plead guilty to one count of mishandling files, a felony, he would be set free right away. Alberta called her brother, Chung, to share the news, and they asked each other, “Is this a good thing?” but neither was sure. They had always insisted to supporters that their father would not back down.

But Sylvia, she didn’t care anymore what happened in the courtroom. He could stay in jail and fight for acquittal or come home now, a felon. He would have to choose. But she was worried for him, and worried for herself, and especially worried for Alberta, who was speeding toward a nervous breakdown, talking now about a hunger strike.

Sylvia tried not to expect anything as the family convened at the courthouse. She settled her nerves, sitting with her children as the courtroom came to order. Her husband stood before the judge in his gray suit and his white shirt, in his blue tie, looking tired. “Okay,” the judge said. “I understand the parties have finally reached a plea agreement.”

“That is correct,” said the prosecutor.

“Yes,” said Lee’s attorney.

The judge turned to Sylvia’s husband.

“I need to advise you, Dr. Lee, that citizens who are convicted of felony crimes lose rights of citizenship. Those include the right to hold public office, the right to serve on a jury, the right to possess a weapon, and the right to vote. You will be giving up your right to cast a ballot that would express your opinion of what was done to you. Do you understand that fully?”

“Yes,” said Lee, to be with his family, even without his rights.

The judge turned his attention to Lee’s attorney. “You turned a battleship in this case,” he said. “I think that at a trial you would be extremely effective. Knowing all that you know, it’s still your considered judgment that it is in his best interest to proceed with a plea of guilty?”

“Yes,” said Lee’s attorney.

“At this time, I will ask Dr. Lee, how do you plead, sir?”

And the courtroom winced in anticipation of that word, but Sylvia’s face was a desert.

“Guilty,” said Wen Ho Lee.

Wil S. Hylton is a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine and the author of Vanished. His complete archive is available on Longform.